‘All This Rugged Beauty’

Peeking through a grove of svelte, white aspens, dusty hills ascend from sagebrush, giving way to jagged, rocky peaks piercing an impossibly blue sky that extends as far as the eye can see.

“The drama of the landscape here — the wide-open spaces, the mountains larger than life, the natural beauty — you feel yourself in the environment in a different way. You feel yourself as this smaller thing … and that’s what I really love about the Eastern Sierra. All this rugged beauty.”

That’s Carol Blanchette talking about her backyard. Her actual backyard.

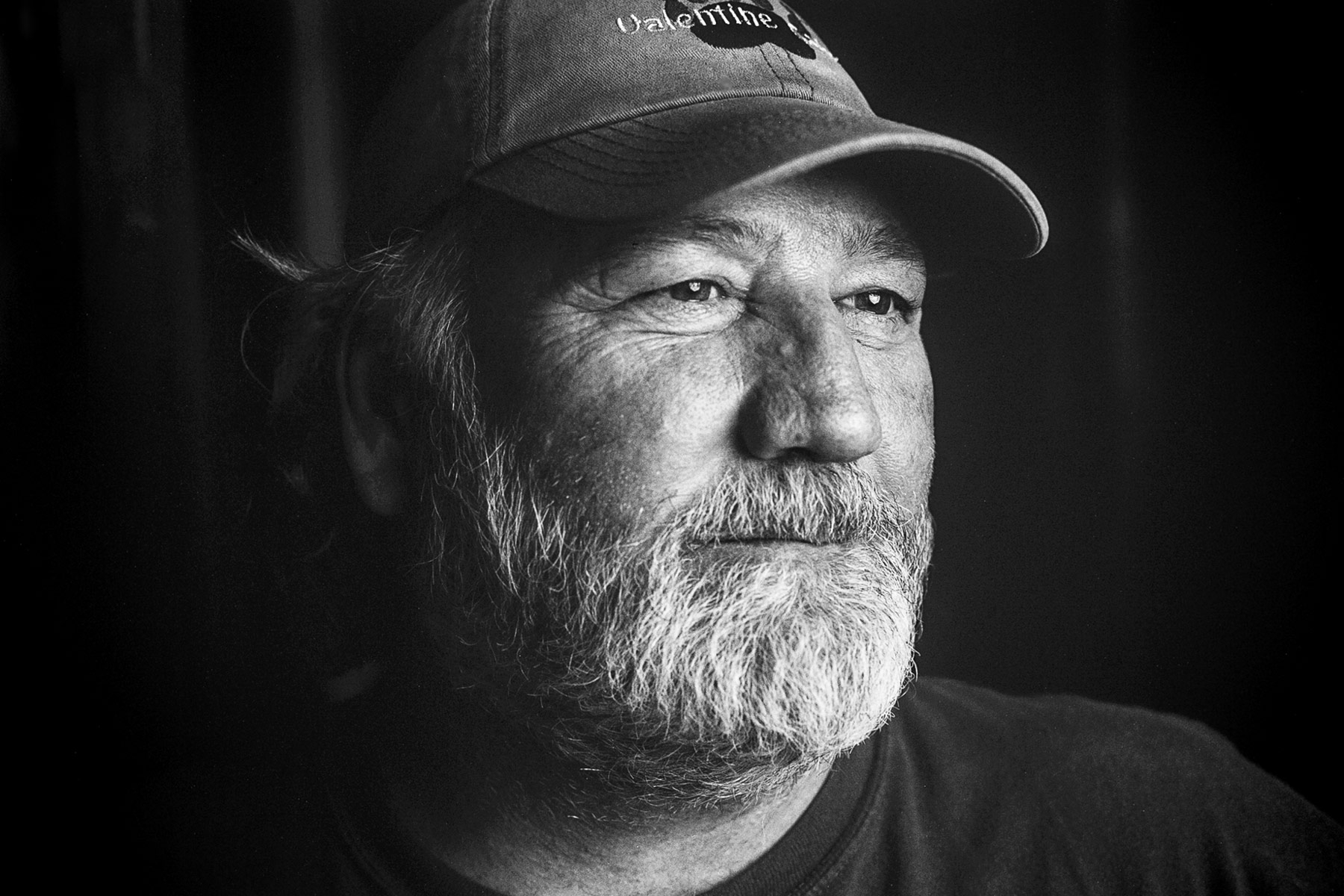

Carol Blanchette, director of the Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserve

As the director of UC Santa Barbara’s Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserve (VESR), a two-site research outpost in Mammoth Lakes, she lives and works in that exact dramatic landscape she loves. Both her house and her office at Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Laboratory (SNARL) — the second field station, Valentine Camp, is just 15 miles up the road — look out on those very hills and aspens and peaks.

“Every day I walk out here and I’m blown away that I have a place like this that is protected, where I see people doing research, and see kids out exploring,” said Blanchette, who assumed the role just this summer upon the retirement of longtime director Dan Dawson, who ran the reserve for 37 years. “This is the dream job.”

‘An Important Role’

Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserve (VESR) is among UCSB’s — and the University of California’s — most prolific sources of ecological research. It is part of the 39-site UC Natural Reserve System (NRS), which boasts more than 750,000 acres of protected natural land and is the largest of its kind in the world.

UCSB administers seven reserves — the most of any UC campus — including Coal Oil Point on the coast just off campus and Sedgwick Reserve in Santa Barbara County’s wine country. Valentine Camp and SNARL are the farthest-flung.

“These reserves are important because they provide venues for researching Eastern Sierra ecology and hydrology, including snowpack and snow melt, which serve the entire Southern California region,” said UCSB’s NRS director Patricia Holden. “And with drought and climate changes in California, the UCSB NRS in the Eastern Sierra importantly serves the state.

“Field stations in general are playing an increasingly important role in understanding how all lands can be managed into the future,” added Holden, a professor at UCSB’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. “In many ways, we have a similar objective as the National Park Service (NPS): To steward natural resources. But the Natural Reserve System emphasizes research, and thus wherever we can partner with the National Park Service — for example, by managing reserves on National Park Service lands, as we do at Santa Cruz Island Reserve — the reserve system can enhance the research portfolio of the park service.”

‘A Portal Reserve’

Founded by the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife in 1935, SNARL has been a research outpost for more than three-quarters of a century. Originally known as Convict Creek Experiment Station, it was established to study the success of hatchery trout in a native stream. Over time the name changed and the research focus broadened.

UCSB acquired the 55-acre SNARL in 1973, not long after receiving the 156-acre Valentine Camp as a gift from the Valentine family in 1972. Both properties joined the still-nascent portfolio of the NRS, which launched just a few years prior, in 1965.

“SNARL was unheard of nationally when I first got here, and so was the NRS — it wasn’t on the research radar,” said Dawson, who was hired as reserve director in 1979. “I’m proud to say after 35-plus years of quality work and research, we are held in high regard by the scientific community at large and by the people who come here.

“Because we’re nested in an area that’s almost entirely public land we have access to millions of acres of forest service, national park and wilderness areas,” Dawson added. “I view SNARL as a portal reserve, a stepping off point into all that area of public land, making it a much more important and significant site than its 56 acres belies. It is now one of the most heavily used and active and productive sites in the NRS.”

UCSB research biologist Roland Knapp uses SNARL, and its new molecular biology lab, as just such a portal. Most of his work is in the high alpine lakes of Yosemite National Park, where he is helping to recover and rebuild populations of the native California mountain yellow-legged tree frog that have been extirpated from more than 92 percent of their geographic ranges.

It’s name aside, SNARL is, in Dawson’s words, “so much more than aquatic biology.” As is Valentine Camp and all NRS sites, it is open to professional researchers across the spectrum of field sciences, “from geology and geophysics, to animal behavior and physiology, to plant response to climate change.”