'Otherworldly'

As you ascend the steep, rough switchbacks, holding tightly to a hand-built bench in the rear of a flatbed pickup truck, water wells in your eyes. Not from fear, but from sheer disbelief.

What you see: A rugged landscape of every hue, undeveloped, untouched. Wild. What you hear: Nothing. Not a single thing but your own breathing. You inhale and the air catches in your throat. What words apply?

Insert your preferred superlative here. Magnificent. Spectacular. Glorious. Grab a thesaurus and take your pick. The adjectives will come fast and furious, but the perfect word eludes in the face of beauty indescribable.

This is California at its ecological and unrivaled finest. This is Santa Cruz Island Reserve, part of the seven-site UC Santa Barbara Natural Reserve System (UCSB NRS). It’s about 25 miles off the Santa Barbara shoreline — and a whole world away from modern, metropolitan reality.

“Being out here, in one sense you can almost think you’re a time traveler, and that you’ve gone back in history,” said Lyndal Laughrin, the reserve’s director for nearly 50 years. “This is the way California used to be. This island definitely could have gone the way of Catalina, full of people. But it didn’t happen here, and it’s just been an amazing opportunity and a privilege to have been able to be part of it.

“There are days you can go someplace and you’re virtually the only person for tens of square miles,” he added. “I can’t argue with how awesome this place is. It speaks for itself.”

Does it ever.

‘A place apart’

The biggest island off California’s storied coast, Santa Cruz is home to the world’s largest recorded sea cave, the tallest peak on the Channel Islands and the greatest number of plant and animal species across the entire chain. At 24 miles long and six miles wide, with 62,000 acres in sum, it is nearly three times the size of Manhattan.

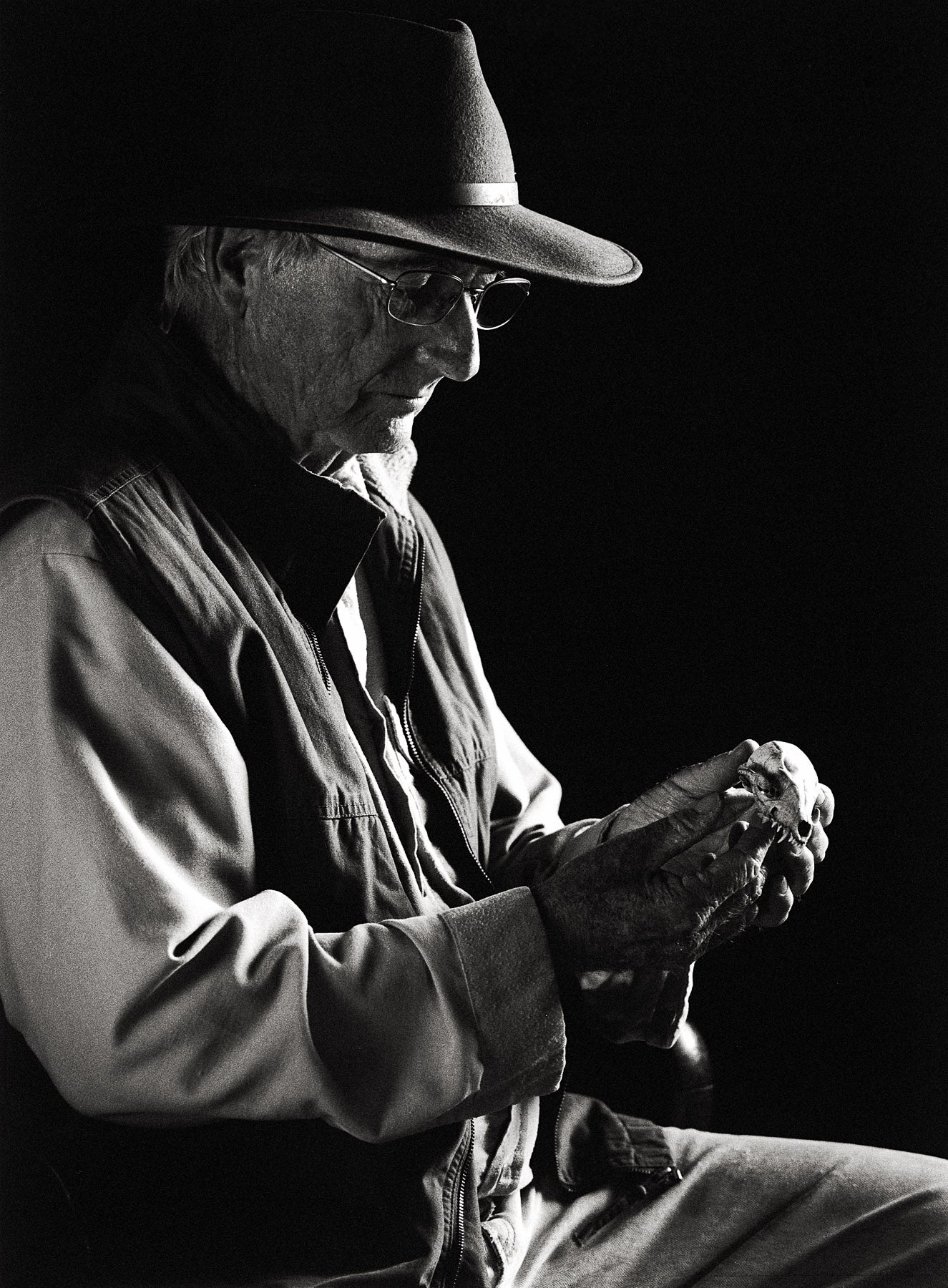

Reserve Director Lyndall Laughrin holds the tiny skull of a Channel Islands fox, a dwarf version of a grey fox. Laughrin played a key role in saving this endemic species from extinction.

Photo Credit: MATT PERKO

Legend holds that it was named for a priest’s staff, inadvertently left behind during the 1769 Portola expedition. A native Chumash Indian is said to have found the staff and eventually returned it to the priest, leading the Spaniards to thereafter refer to the place as “La Isla de Santa Cruz,” or Island of the Sacred Cross.

Archaeology from Santa Rosa Island, a few miles west, suggests humans lived on the Channel Islands more than 13,000 years ago. At one point, as many as 2,000 Chumash spread across 10 villages on Santa Cruz, where evidence of humans so far dates back 9,000 years. That’s according to Laughrin, an island historian by virtue of his tenure here, half a century and counting.

“Sometimes, you’ll be walking along and find a blade or an arrowhead or some beads,” he said, coming upon a fairly common sight — “worked rocks.” To the untrained eye they look simply like, well, busted rocks. But in fact, said Laughrin, any rock here with one hard-broken edge and a smoothed-out opposing side is almost certainly a former Chumash hand tool.

Animal skulls and skeletons are scattered in abundance across the island. An impressive collection of this biological ephemera — curated ad hoc over the years by visitors who find, then leave them behind — surrounds a tree fronting the UCSB field station. Weeds grow through those that have been there the longest.

Through the kaleidoscope

Two rugged mountain ranges, deep canyons, perennial springs and streams, plus a full 77 miles of coastline cliffs, expansive beaches, pristine tidepools and sea caves. Landforms on Santa Cruz are as numerous as they are diverse.

The island’s central valley, a faultline running right through, is like an ecological wayback machine. From an elevated vantage point — a mere 20-minute, treacherous drive west from the UCSB field station — you can gaze across a Jurassic-era ridge some 140 to 160 million years old. The volcanic formations date to the Miocene, some 14 to 15 million years ago.

“You could put your feet across two different ecological eras right here,” Laughrin said, surveying the valley below. “The views are different at different times of day, during different seasons or weather, and from different angles. It’s like looking through a kaleidoscope. You turn it and things shift themselves around. And you never tire of what comes next.”

With unrivaled diversity in geology and ecology alike, and microclimates to go along with them, a drive across the island is like traveling from Baja California to Santa Barbara to coastal Northern California — all in three hours’ time. In a single bumpy ride, you’ll move from a cool forest to a stretch so hot, dry and rugged it feels like a desert. You’ll come upon areas impossibly lush and green, and end at an expansive cliff — blanketed in spring by coreopsis and other wildflowers — where the ocean stretches out to the sky.

‘Privilege and responsibility’

The UCSB NRS is part of the larger UC Natural Reserve System, founded in 1965 to provide undisturbed environments for research, education and public service. With 750,000 acres of protected natural land across 39 sites, representing most of the state’s major ecosystems, it is the largest network of its kind in the world.

UCSB has seven properties in its care, the most of any UC campus. Among them are the two-site Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserve in Mammoth Lakes; Kenneth S. Norris Rancho Marino Reserve in Cambria; Sedgwick Reserve in Santa Barbara’s wine country; Carpinteria Salt Marsh Reserve just south of Santa Barbara; and Coal Oil Point Reserve in Goleta, adjacent to the campus.

Santa Cruz Island Reserve was one of the system’s early additions. The island was used for commercial ranching from the mid-1800s to the late 1980s; its final private owner, Dr. Carey Stanton, initiated a relationship with the UC by welcoming scientists to conduct research. A field station was established in 1966. The facility, along with Stanton’s 54,520 acres, officially became part of the UCNRS in 1973.

Seeking to protect and conserve the island in perpetuity, Stanton sold his property itself to The Nature Conservancy, which still holds and manages it today, licensing the university to run the reserve for research and teaching. The National Park Service owns and operates the eastern 25 percent of the island.

“It is one of UCSB’s great privileges, and responsibilities, to operate a field station on Santa Cruz Island,” said Patricia Holden, director of the UCSB NRS and a professor at the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. “Generously sited on The Nature Conservancy’s property, and loyally directed by Lyndal Laughrin for over 40 years, the SCIR has opened the eyes of countless schoolchildren, undergraduates and graduate students to this otherworldly sanctum of nature and history. The SCIR supports research the island-over, including on National Park Service lands, which — in this time of rapid environmental change — is unequivocally vital for managing not only fragile island ecosystems but also our own mainland futures.”