‘Sense of Wonder’

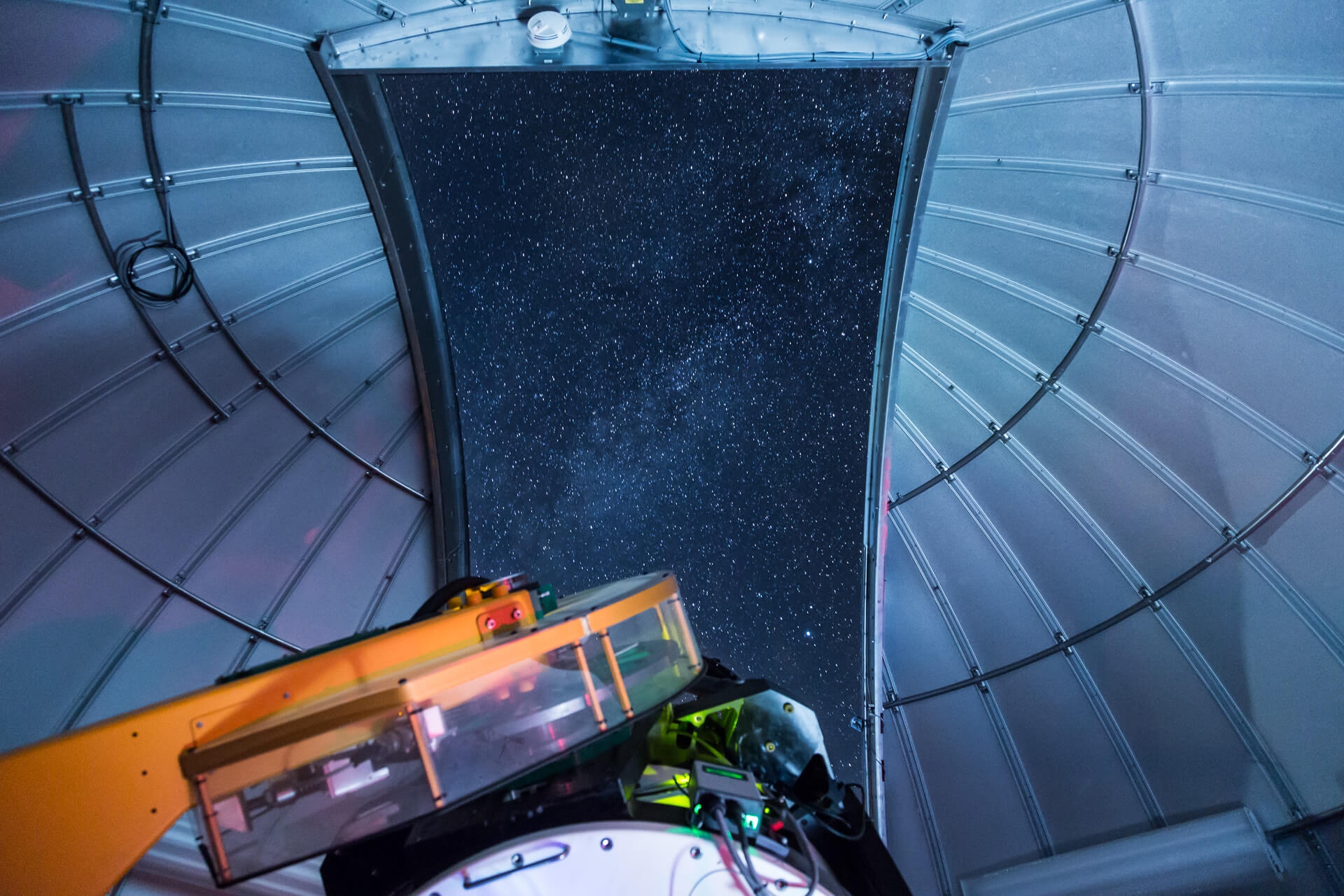

The night sky over Sedgwick Reserve is a wonder of a thing. Sunset begins in pale purple hues that give way to darkening shades of glorious blue, and then the colors fade to black, supplanted by an onyx expanse ablaze with diamonds. Seeing it all — the stars and space beyond — from inside a hilltop observatory, it’s mesmerizing.

Daytime at this 6,000-acre place is pretty stunning, too.

With rolling hills and sweeping grasslands that are lately more green, courtesy of recent rains, and a ridge packed with colorful outcroppings of serpentine rock, Sedgwick in the sun is a marvel unto itself. A landscape of classic oak savannahs bordered by coastal sage scrub and chaparral, it’s quintessential Santa Barbara ranchland.

‘Two Reserves in One’

“This reserve, in my opinion, is worthy of being a state park or a national park,” said Kate McCurdy. And she should know. Now and for the last decade the reserve’s resident director, McCurdy spent a dozen years with the National Park Service, including a long tenure at Yosemite, before taking the helm here. “So many unique features. And just so beautiful.”

Indeed.

Sprawling across nine square miles at the base of Figueroa Mountain in the famed wine country of the Santa Ynez Valley, Sedgwick is among the seven-site constellation of ecosystems that is UC Santa Barbara’s Natural Reserve System (UCSB NRS). It’s got two intact watersheds and an earthquake fault running straight through the middle of its two distinct landforms: an alluvial lower half and the serpentine outcrop up top.

“It’s like having two reserves in one,” McCurdy said.

Kate McCurdy, resident director at Sedgwick Reserve

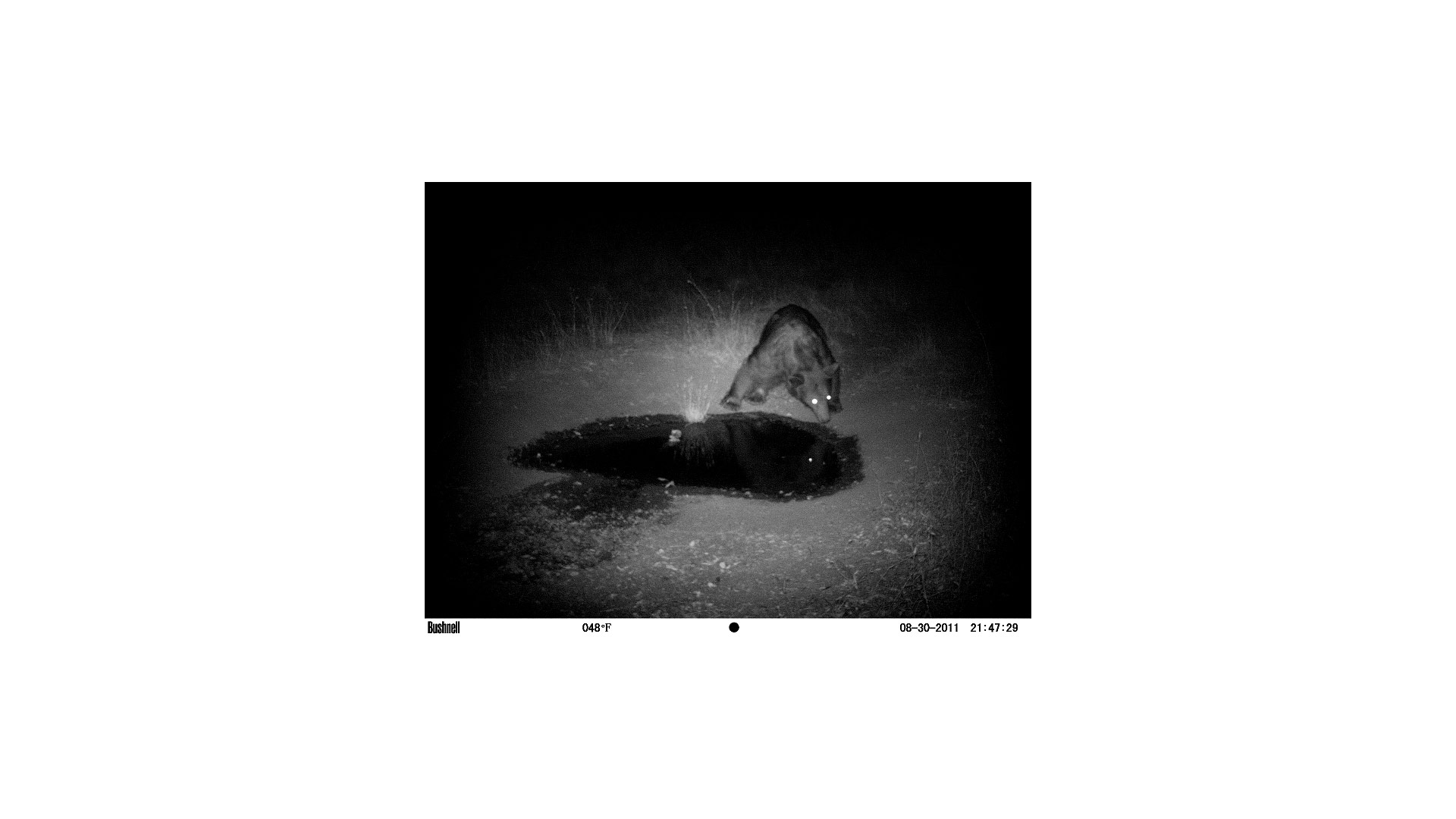

“Coming here from the National Park Service, I was initially worried it wouldn’t be big enough, ” McCurdy said. “Turns out that nine square miles is plenty big for a wildlife biologist. To see just how many bears are here in the fall, the year-round wildlife, the mountain lions, the coyote packs always howling at night and all the birdlife. It’s a great place to work.”

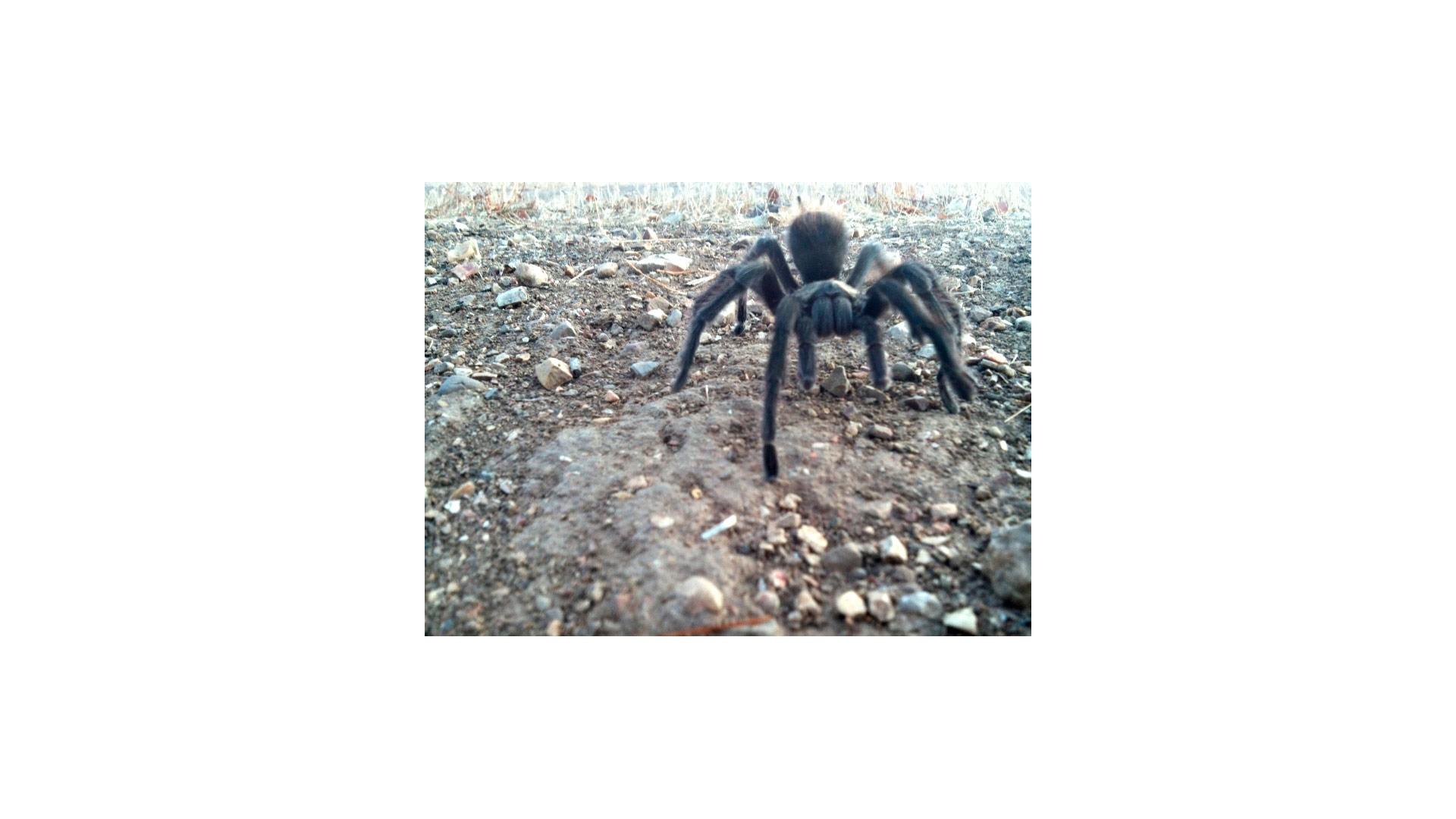

Sedgwick has habitats for everything from black bears and mountain lions to pallid bats, golden eagles, tarantulas and nearly 200 different species of moths. It boasts a diversity of geological features and vegetation that includes a rare collection of the region’s most prized plant communities, such as coastal sage scrub, native grassland, chaparral, gray pine forest, and coast live oak and blue oak woodland.

“On the edge of a valley being developed fairly rapidly, being able to take a prime piece of land like this and put it into conservation, and use it for learning about how to preserve ecosystems, has really been a rewarding use of the last decade,” said McCurdy. “We need to make sure we’re studying the right things and protecting this place as best we can. Especially seeing how climate change has impacted a lot of the places we’ve been working — seeing water dry up and trees dying — it feels like an important time to be paying attention. This place won’t look the way it does now in another ten years.”

‘A Place of Many Superlatives’

The UCSB NRS is part of the larger UC Natural Reserve System, founded in 1965 to provide undisturbed environments for research, education and public service. With 750,000 acres of protected natural land across 39 sites, representing most of the state’s major ecosystems, it is the largest network of its kind in the world.

With seven properties in its care, UCSB runs the most reserves of any UC campus. Among them are the two-site Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserve in Mammoth Lakes, Kenneth S. Norris Rancho Marino Reserve in Cambria, Santa Cruz Island Reserve, Carpinteria Salt Marsh and Coal Oil Point in Goleta just adjacent the campus.

Added to the NRS portfolio in 1997, Sedgwick is among the largest sites in the whole system, and one of its most public. In addition to regular use by researchers — and increasing use for university-level instruction — the reserve has a robust special event program supported by volunteer docents that include outdoor education classes, guided monthly hikes, public lectures, workshops and community events.

“Sedgwick is a place of many superlatives, and probably the most important one is that it has the largest, most engaging docent program in the Natural Reserve System,” McCurdy said. “The docent program, which was founded in 2002, is sustained by 75 self-governing volunteers who contribute a thousand collective days of service annually in support of Sedgwick’s outreach, conservation and citizen science programs. They are an amazing cadre of dedicated neighbors, UCSB retirees and working professionals from around the county who care passionately about Sedgwick.”

Opportunities Abound

They’re not alone.

Devotees of this bucolic paradise are many, spanning not just the county, but the reserve system, the UC system and the myriad disciplines therein. Artists and archaeologists, ecologists and geologists, botanists and biologists, historians and geographers — all find ample fodder here. As do astrophysicists, thanks to the Byrne Observatory Telescope at Sedgwick, the only reserve with an astronomical facility.

And then there are the computer scientists.

The reserve is an experimental homebase for UCSB computer scientist Chandra Krintz’s effort to enable more sustainable farming through technology. Her software-based project, SmartFarm, employs sensing systems and analytics to address problems that farmers face, from irrigation leaks to the weather. Krintz and her team frequently test their system at Sedgwick, which has an agricultural easement.

“Sedgwick is an amazing environment and location for research and hands-on education in technology-driven ecology and agriculture,” Krintz said. “Researchers are supported by an incredible and forward-thinking director and staff, and are offered a tremendous opportunity for cross-disciplinary collaboration and scientific advance.”

Research at Sedgwick is as diverse as its ecology. Among recent inquiries: the genetic diversity of oak trees, serpentine habitats, competition among plant species, soil morphology, cultural history and rattlesnake ecology. As at most other reserves, climate change and the effects of drought on both flora and fauna are a huge focus.

“All these colorful rocks, the serpentine, are pushed out of earth’s crust through the uplifting that happens along the edge of the earthquake fault, like the top of a pizza being scraped off. It releases a lot of those beautiful rocks that wind up in our creek bed and decorating our field station.

—Kate McCurdy, Resident Director, Sedgwick Reserve

And it’s not just professional scientists doing the work. Opportunities abound equally for students at Sedgwick, a regular and popular stop on the multi-reserve circuit traveled each quarter by the UC-wide course California Ecology and Conservation. Every undergraduate campus in the system was represented in the fall 2016 cohort, which spent 10 days camping, and researching, at the site.

“Being here at Sedgwick has been so inspirational,” said Jennifer Adachi, a UCLA senior in the NRS course, whose Sedgwick project focused on acorn preferences in two bird species. “It’s spectacular. This experience teaches you a lot about what you like to do, and what you don’t. Coming out of this I think I will have a much more profound understanding of things that I will pursue later. Conservation is something that’s so important, and it’s something I’m going to dedicate the rest of my life to.”