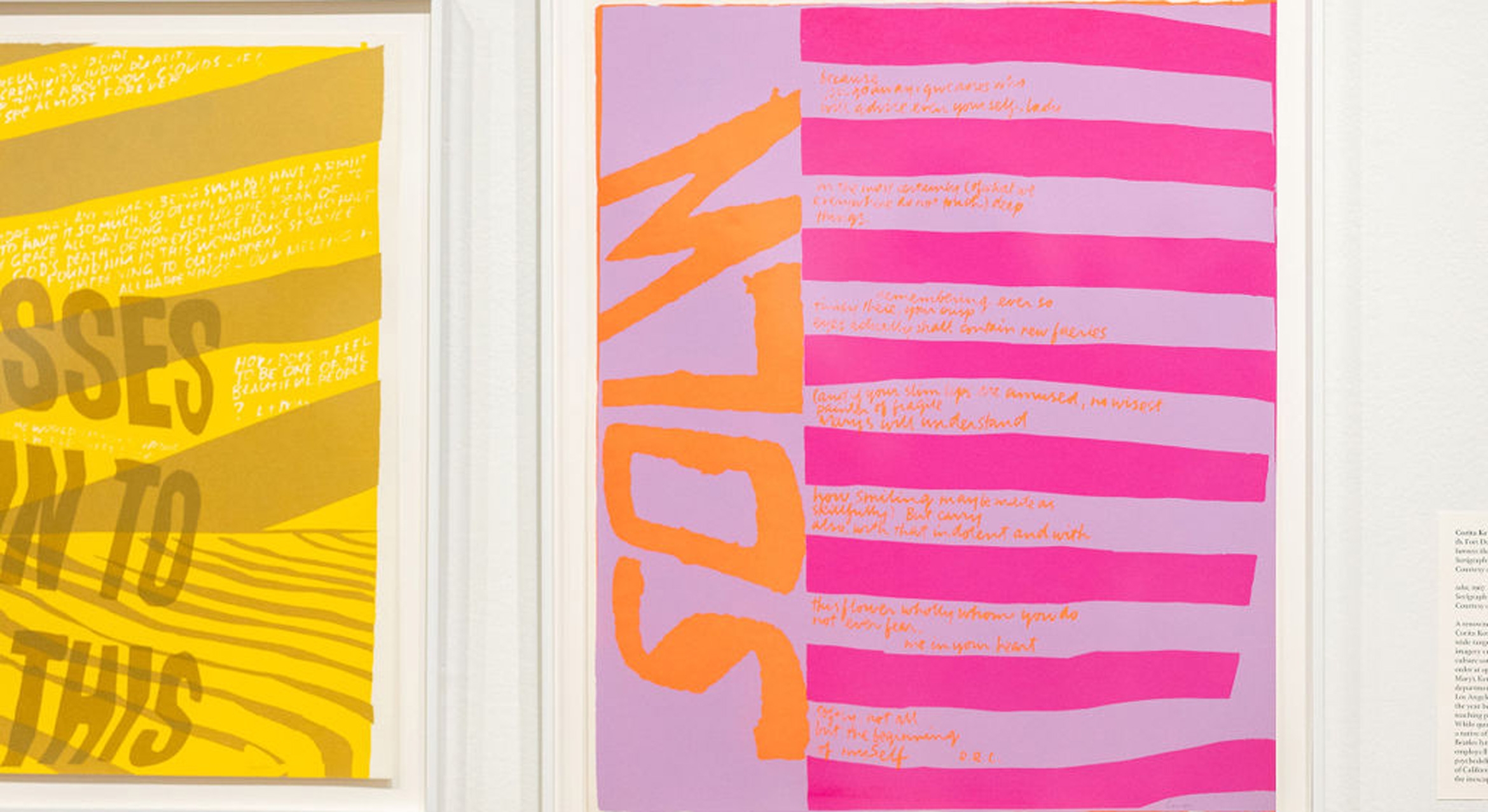

Imagine driving through California’s sunlit streets, approaching a crosswalk that tells you to “SLOW.” But something’s off — it’s misspelled: “SOLW.” The word echoes in your mind as soul.

This small twist — slow becomes soul — captures the essence of Corita Kent’s playful yet profound work. Featured in “Public Texts: A Californian Visual Language” at UCSB’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum, the piece critiques California’s car culture while offering a spiritual nudge to pause, reflect and look deeper. It’s a simple misspelling, but one that carries weight in California’s complex, ever-shifting identity.

“That moment of contradiction — where the sign tells you one thing, but the way you say it tells you something else — is exactly what I love about this piece,” said Alex Lukas, the exhibition’s curator and associate professor of print & publication in UCSB’s Department of Art. “It’s playful, but it’s also a comment on something much larger: the relationship between language, perception and the lived experience of California.”

Kent’s work serves as a gateway to the broader themes of the exhibition, highlighting how text-based art in California subverts expectations, challenges dominant narratives and reflects the state’s diverse, complex culture.

The interplay between language and visual art has long been a defining characteristic of California’s creative landscape. In “Public Texts” Lukas brings together a group of artists whose work reflects the diverse and often surprising ways in which text functions within contemporary visual practices.

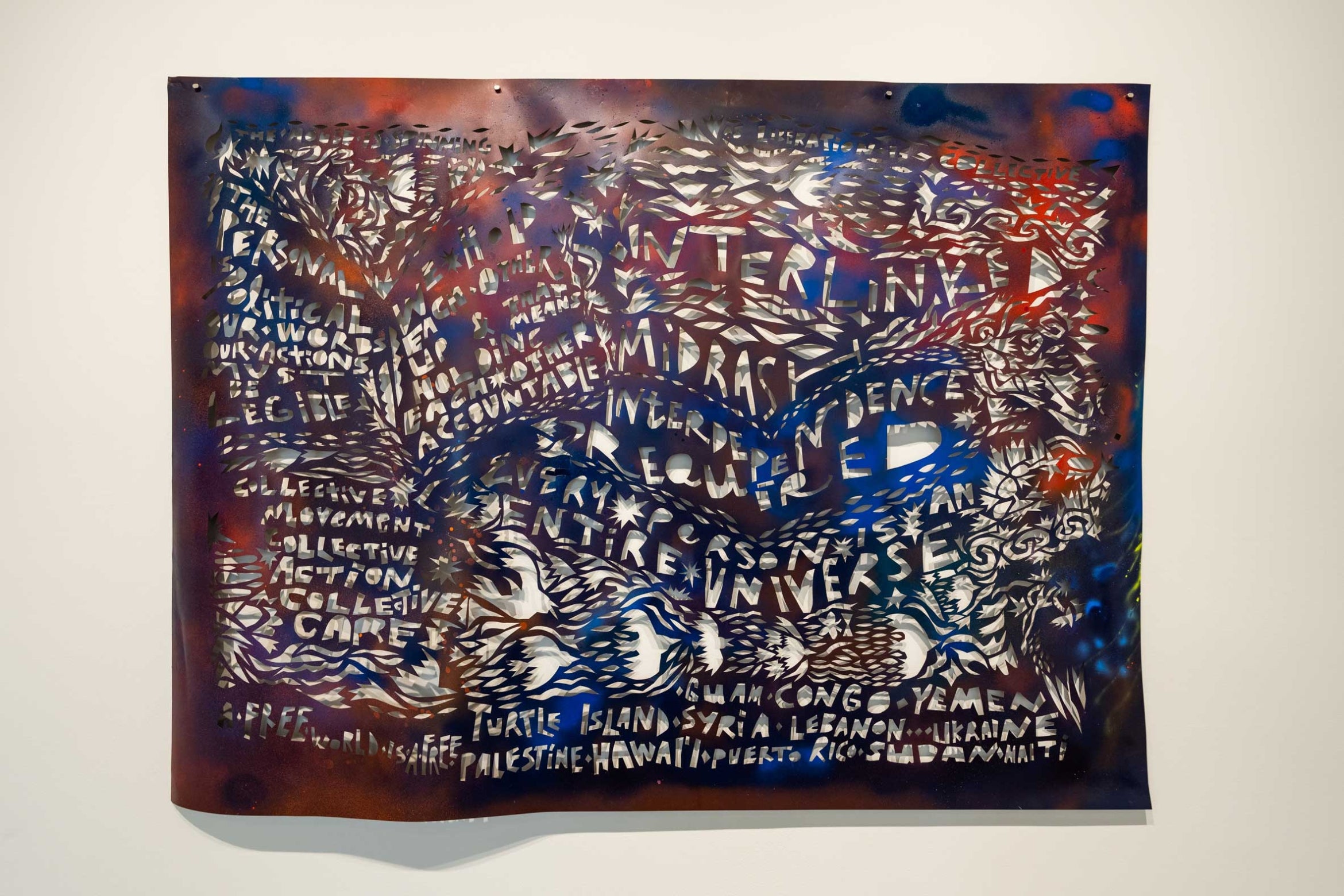

Spanning a wide range of mediums, from painting and drawing to printmaking and public interventions, the exhibition brings together over 20 artists who, through their distinctive use of text, delve into the cultural and political complexities of California. As Lukas explained, the exhibition is meant to engage with the “web” of California’s visual and cultural history, showcasing how these artists reflect and reshape the state’s unique place in the world.

“What I’m trying to do with this show,” said Lukas, “is to explore how these Californian artists are using text to not just create aesthetically interesting work, but to reflect on the state itself. I think of it as a portrait of a place — one that is constantly defining and redefining itself.”

The artists in “Public Texts” are united by their relationship to California, whether they were born here, migrated here, or simply shaped by its sprawling, diverse landscape. The term “rooted in California” that Lukas uses to describe the exhibition is intentionally expansive. From the lively streets of San Francisco to the quiet expanses of Southern California, the exhibition encapsulates a variety of experiences that together form the state’s visual language.

But while the show touches on the rich, often contentious history of California — marked by waves of migration, colonization and cultural exchange — Lukas is equally interested in how text in these works challenges the boundaries of art itself. “I think one of the show’s main questions is about the balance between reading and seeing,” he said. “How does the written word work in tandem with the visual in ways that complicate our expectations of what art should do?”

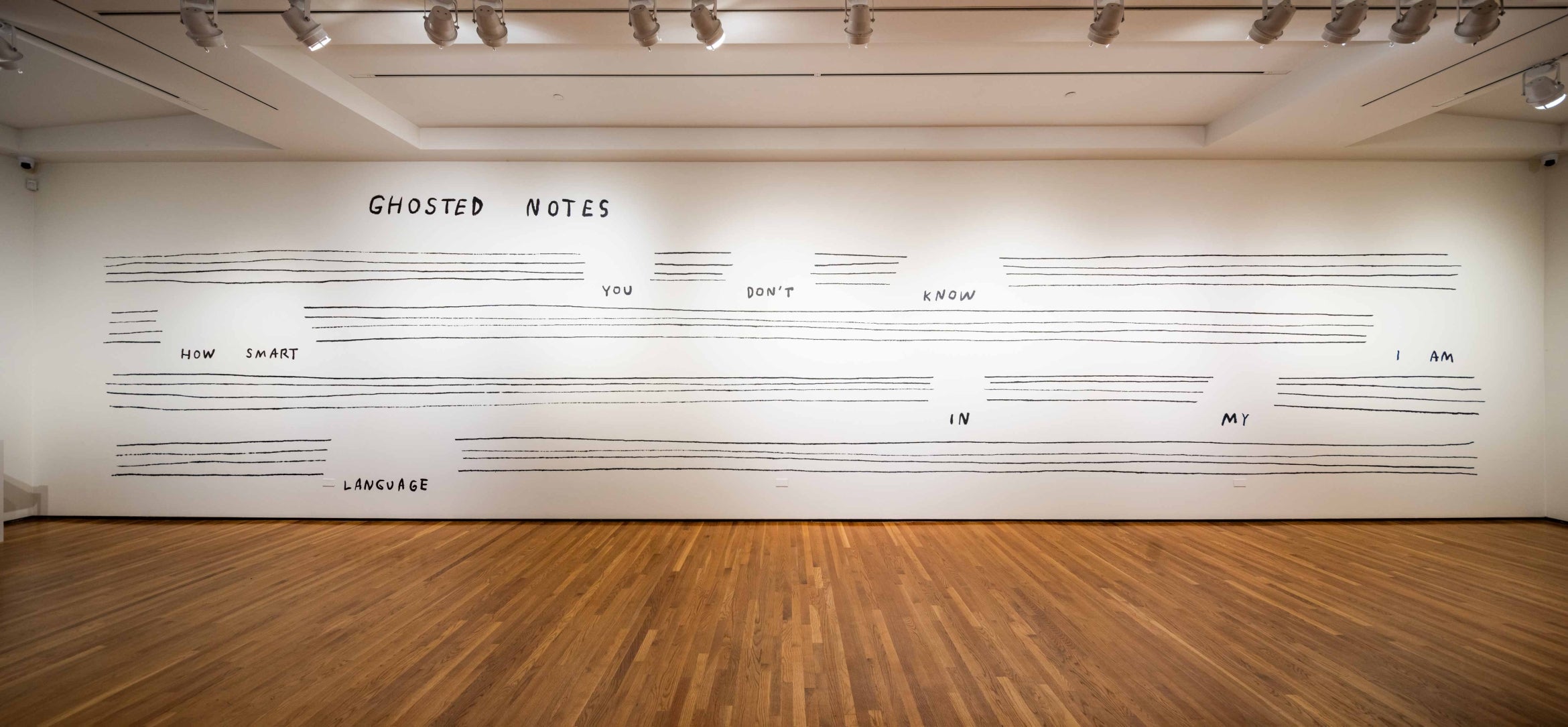

Take, for example, the work of Christine Sun Kim, who uses text to explore the intersection of language and perception. Known for her conceptual approach to sound and silence, Kim’s wall-length mural features a line-based code and the handwritten words, “You don’t know how smart I am in my language.” This challenges our understanding of communication, particularly within the deaf community and diasporic languages.

“Her work is about the limitations of translation,” Lukas said. “You’re looking at something, but can you ever fully understand how smart I am in my language?” For Kim, writing — whether American Sign Language or any other form — isn’t just about direct translation; it’s about questioning the space between signs and how we perceive them.

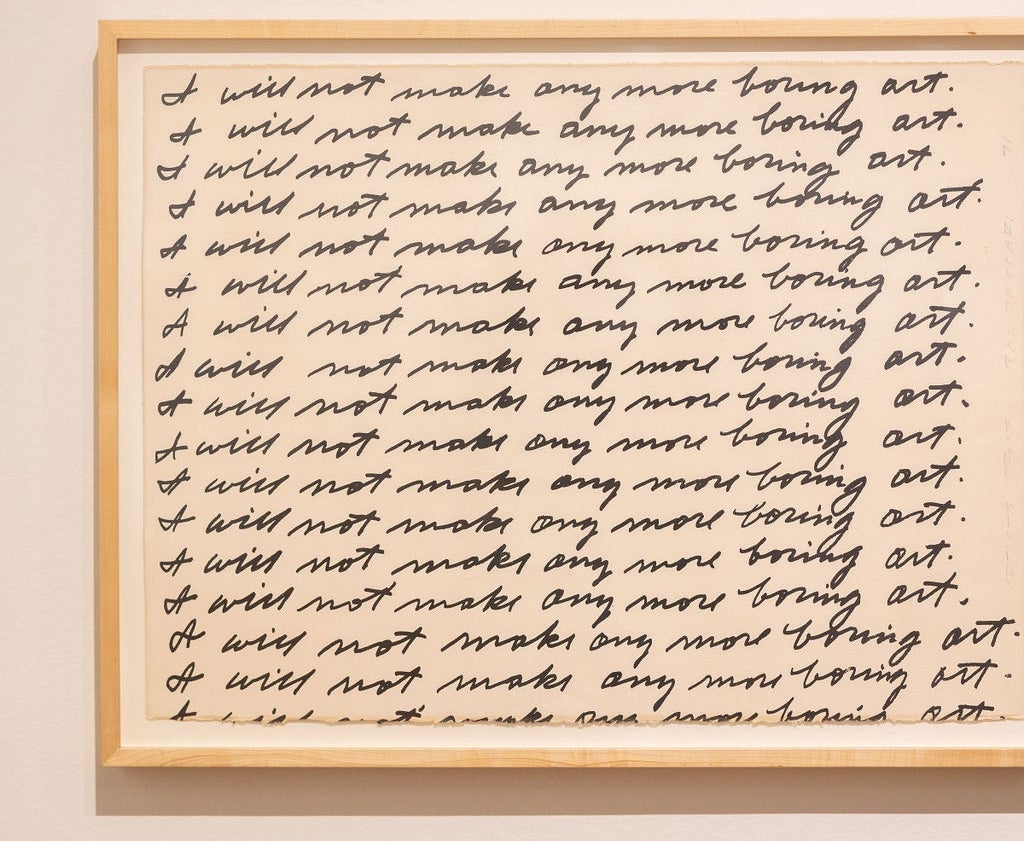

Lukas positions Kim’s work in conversation with John Baldessari’s iconic piece “I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art,” which repeats the phrase “I will not make any more boring art” over and over again, with a hand-drawn simplicity that feels almost mundane — an intentional act of contradiction. “It’s this conceptual twist,” Lukas said, “asking us to speak or verbalize in a way that is more complex than it seems on the surface.”

The contrast between these two works — one a reflection on the limitations of language, the other a playful, defiant reimagining of what art can do — captures the heart of “Public Texts”: the dynamic tension between the written word and its surrounding context.

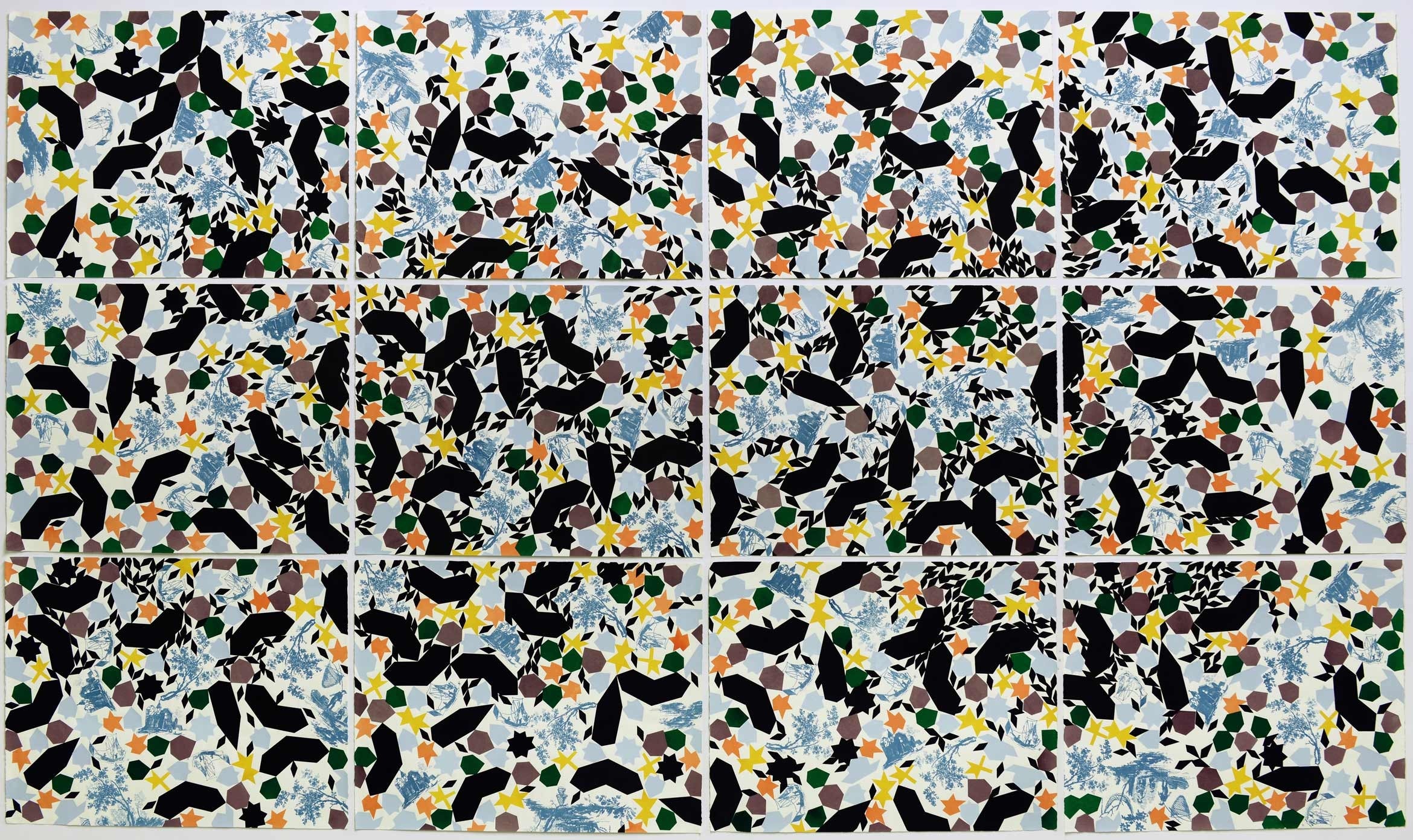

The exhibition also explores the ways in which California’s visual language has been shaped by counterculture movements, graffiti and activism. Barry McGee’s work, for example, draws on the Bay Area’s rich graffiti tradition. As Lukas noted, McGee’s text-based pieces use “coded language” — a style that’s deeply rooted in the vibrant, often rebellious visual language of street art. “For McGee, language isn’t just something to read — it’s something to experience, to decode,” Lukas added. “There’s a vibrancy in how he aestheticizes text.”

But the history of California’s visual culture isn’t just confined to urban streets and countercultures. Corita Kent, a figure central to Los Angeles’ art scene in the 1960s and ’70s, was known for her bright, colorful screenprints. Kent’s work combines pop aesthetics with deeply political messaging. In the context of California’s broader social landscape, Lukas noted, “there’s a certain optimism in her use of text, but it’s always layered with a sense of activism and a call for change.”

In addition to the museum gallery, several outdoor commissions were created for the exhibition. These temporary public artworks expand the exhibition beyond the museum’s walls, providing a dynamic experience that evolves over time. Visitors will have the chance to see these works in their natural environments, responding to the public space and the community around them.

“I love the idea that this show is about connections — between artists, between ideas, between histories,” Lukas said. “It feels like there’s this constant back-and-forth, where one work leads to another, and there are all these overlaps, these unexpected intersections. That’s what makes California such an exciting place for text-based art. It’s a constantly shifting, evolving space.”

“Public Texts: A Californian Visual Language” is on view at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum at UC Santa Barbara Jan. 18–April 27, 2025. “Public Texts” is on view concurrently with the exhibition “Tomiyama Taeko: A Tale of Sea Wanderers.