What does it mean to be ‘Hapa?’ Artist Kip Fulbeck reflects on 25-year identity project

What we call ourselves — and what others call us — has been at the heart of Kip Fulbeck’s art for more than two decades.

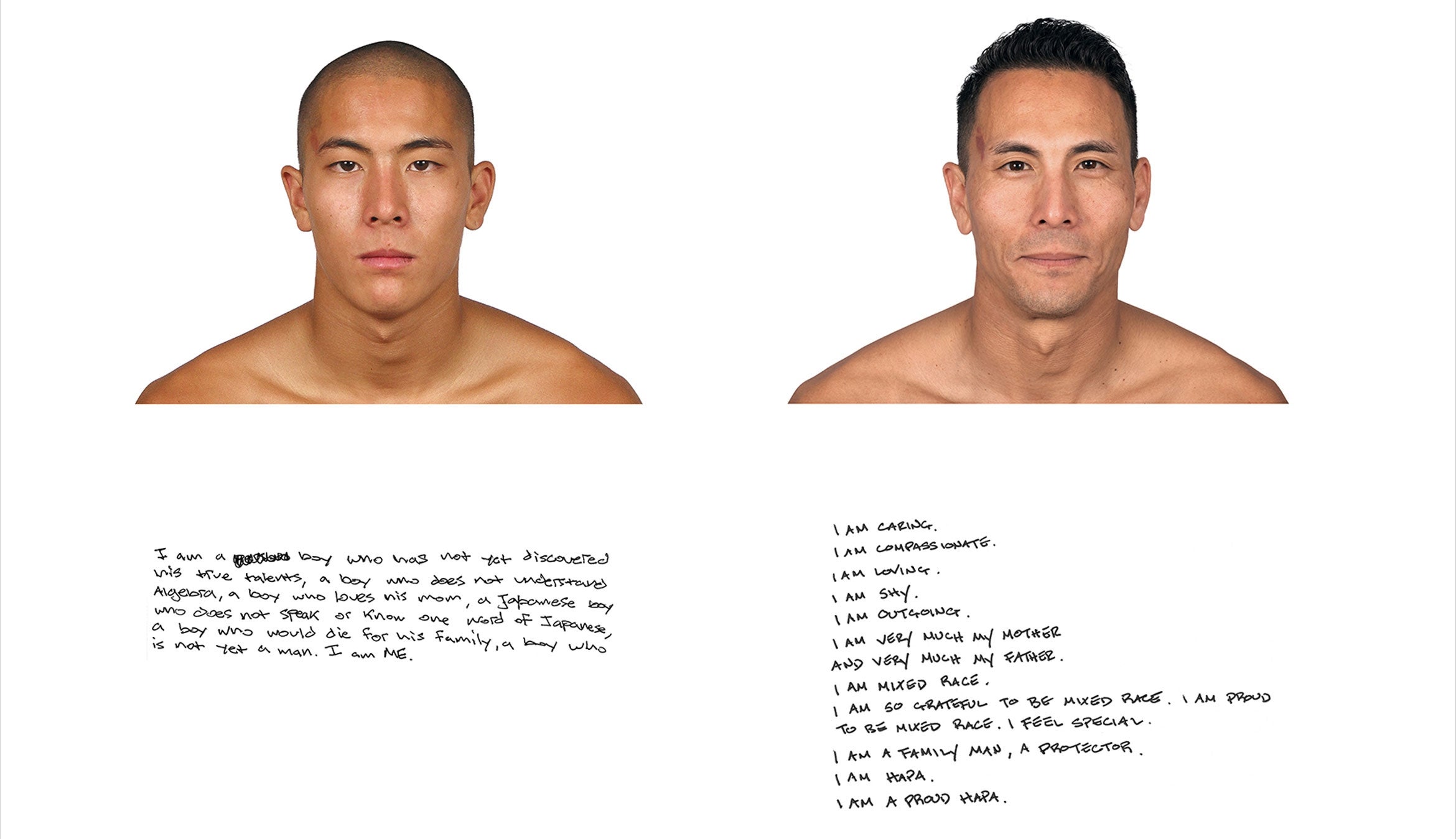

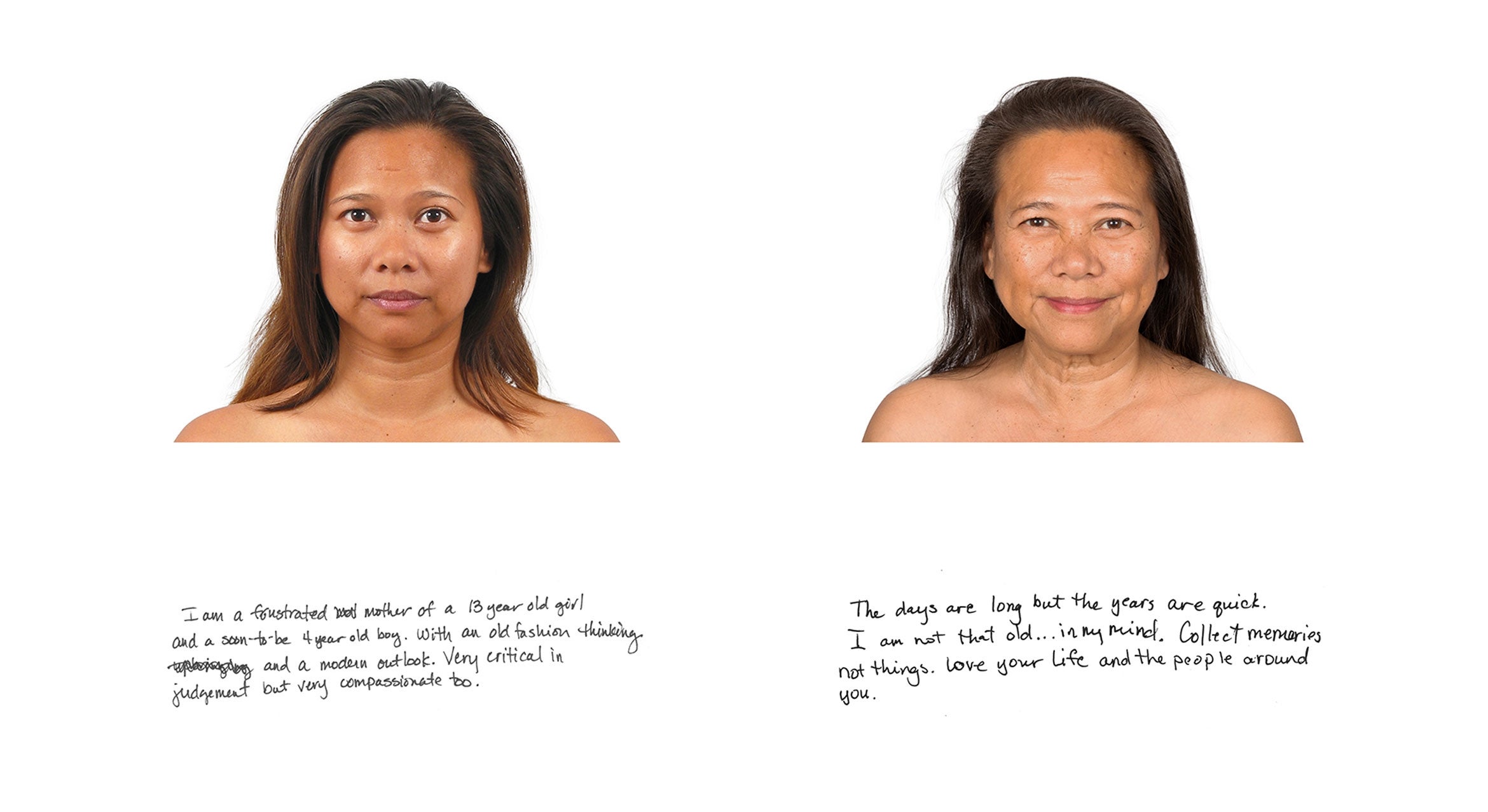

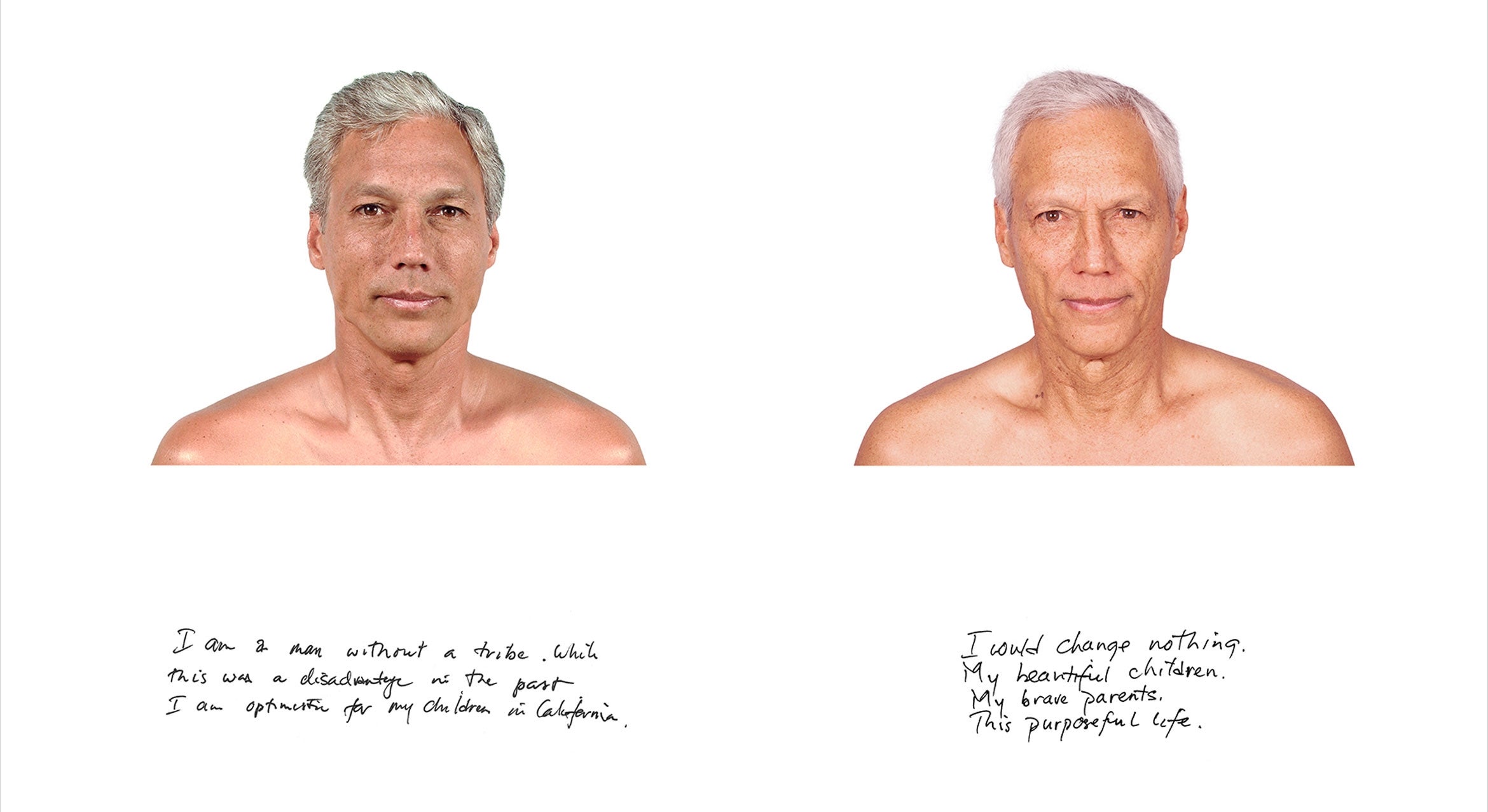

Twenty-five years ago, Fulbeck asked hundreds of multiracial Asian and Pacific Islander Americans a question: “What are you?” Their handwritten answers accompanied stark, unadorned portraits in his groundbreaking exhibition, “Kip Fulbeck: Part Asian, 100% Hapa.”

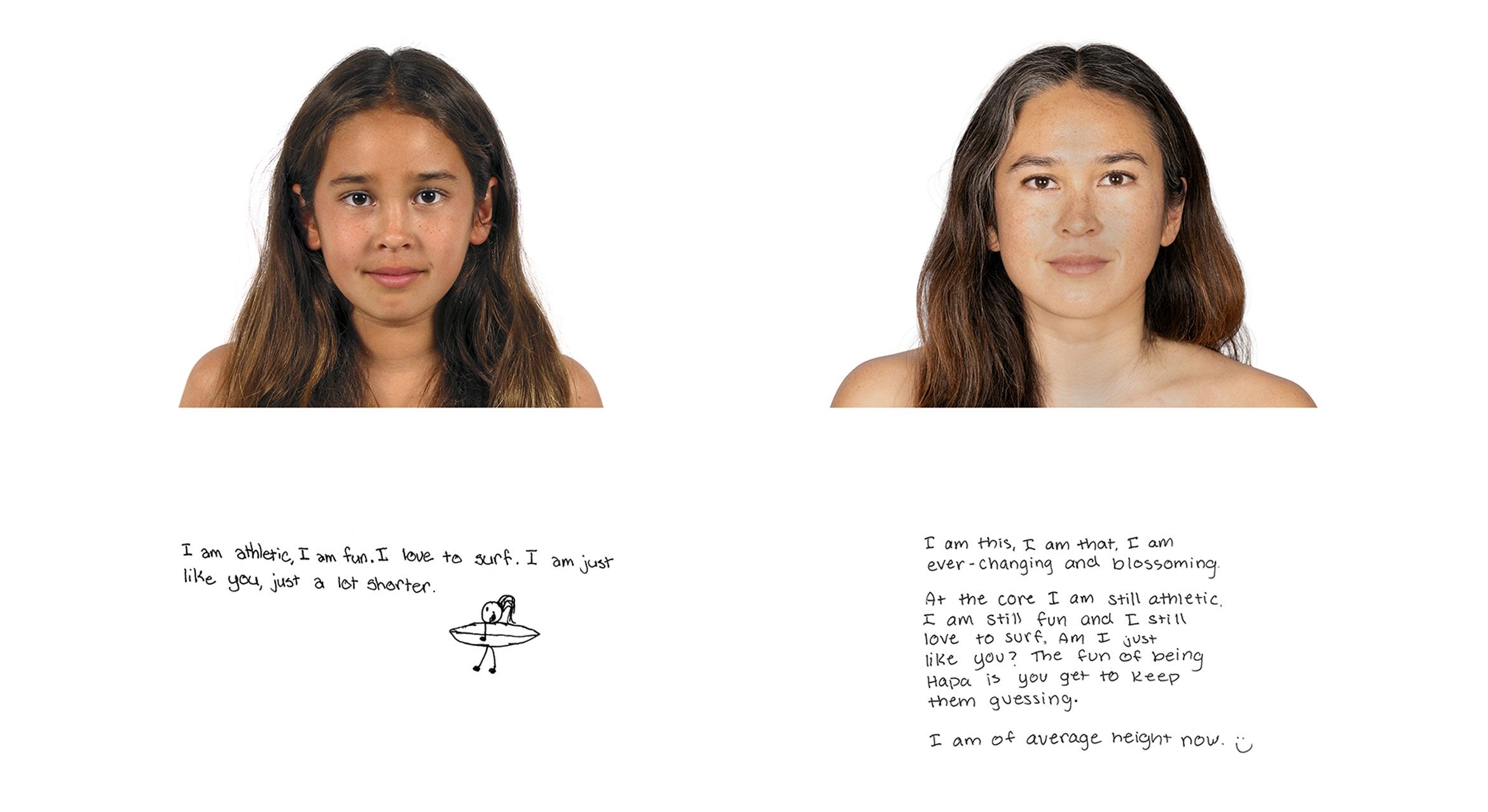

Now, Fulbeck, a distinguished professor of art at UC Santa Barbara, revisits those same participants in “hapa.me – 25 years of The Hapa Project,” at the Museum of Us in San Diego, pairing the original images with contemporary portraits and new handwritten statements, reflecting the participants’ changing identities over time.

“It’s really about agency,” Fulbeck said, “how people define themselves, rather than how others define them. It’s about seeing yourself and being seen on your own terms. It’s about being included.”

The word “hapa,” derived from the Hawaiian term for “half,” has been embraced by many Asian and Pacific Islander Americans of mixed heritage. Originally used to describe children of islanders and White settlers, the term has grown into a marker of community and pride.

“For hundreds of thousands, defining themselves as Hapa meant recognition and acceptance for the first time,” Fulbeck said.

Fulbeck launched The Hapa Project in 2001, photographing over 1,200 multiracial individuals who answered the identity-defining question in their own handwriting. Nearly 25 years later, he has re-photographed 130 original participants, inviting them to share updated statements of personal identity.

“Language constantly evolves, shifts, changes — just like people do,” Fulbeck said. “We didn’t have language to describe people like me as a kid. We had Census forms and health questionnaires and job applications telling us to check one box for ‘race.’”

“(This project) has always been about personal and individual identity,” states the Museum of Us. While race and heritage are central themes, Fulbeck’s focus is on self-definition, giving participants the platform to answer the question in their own terms.

The original portraits were intentionally neutral — no clothing, accessories or directed expressions — to allow participants to shape their own representations. “Participants pick their own photograph, handwrite their own statement, and — in the very purest form — define themselves,” reads the exhibition text at the Museum of Us.

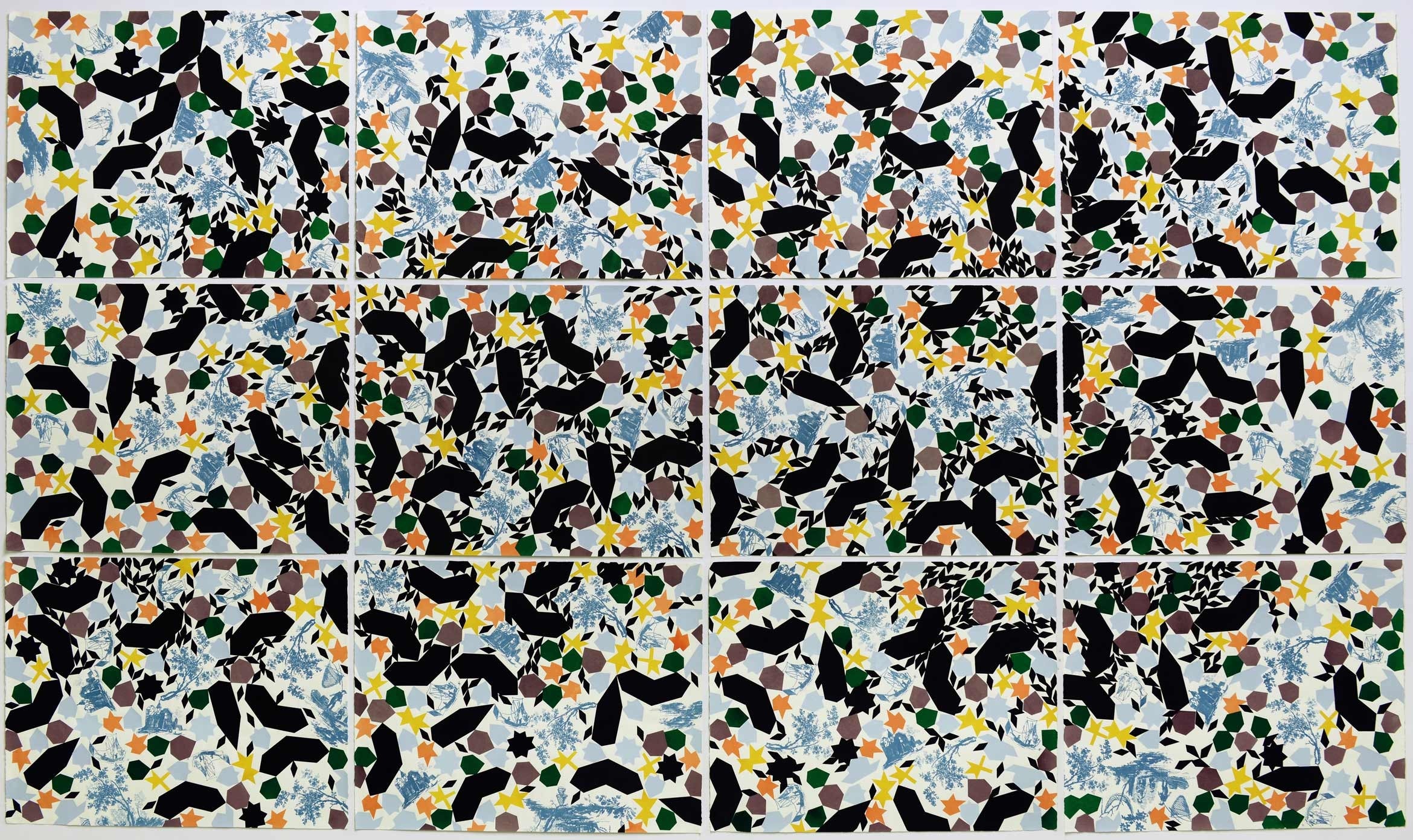

Beyond portraits, the exhibition features Fulbeck’s paintings, calligraphy and eight bamboo-and-steel artist’s books containing hundreds of additional portraits and statements, many never before shown. Visitors are invited to engage directly in the exhibit, contributing their own portraits and handwritten statements to the ongoing dialogue.

As well known as Fulbeck is for The Hapa Project, he may be even better known for “Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in a Modern World,” which opened at Los Angeles’s Japanese American National Museum in 2014 before traveling internationally. In “Perseverance,” he turns his camera toward another form of self-definition: traditional Japanese tattooing, a practice revered for its precision and cultural lineage, with roots in the art of ukiyo-e 浮世絵, yet still stigmatized in its country of origin.

Curated by master tattooer Takahiro “Taki” Kitamura and conceived, photographed and designed by Fulbeck, the first-of-its-kind exhibition featured the full-body work of seven internationally acclaimed tattoo artists, many of whom were shown at this scale for the first time. Sharply composed, Fulbeck’s portraits present bodies as living archives of myth, memory and meaning — while staking a claim for the art form’s place in the museum, a space synonymous with cultural legitimacy.

At UCSB, Fulbeck is known for his dynamic, unorthodox teaching style and deep commitment to creative expression. He has earned multiple honors, including the Distinguished Teaching Award and Faculty Diversity Award, and is especially known for his spoken word course, which was the first of its kind in the country. Blending performance, openness and personal narrative, Fulbeck’s classroom is as much a space for artistic growth as it is for self-discovery.

Fulbeck’s artistic journey is deeply personal. Growing up as the only mixed race child in both his extended family and community, he felt isolated both at school and within his Chinese immigrant household. “At home, I’m the kid that doesn’t speak the language, doesn’t quite like the food,” he recalled. “At school, it’s like, ‘Let’s throw the Chinese kid in the trash can,’ and I’m realizing that I’m the Chinese kid!”

Fulbeck often found comfort in comic book heroes like Spider-Man and the Silver Surfer, outsiders who “couldn’t quite make it work.” His own restless creativity, influenced by ADHD, turned drawing into a therapeutic outlet. “My brain is always going a million miles an hour,” he shared, “It’s exhausting. But when I was drawing, somehow I could focus. I could hear better. Everything else quieted down.”

One such artwork, “100% after if no side effects,” was created during Fulbeck’s first experience with antidepressants. “I remember just drawing sharks over and over while the psychiatrist was explaining these potential side effects to me,” he said. He eventually found balance not through medication, but rather through a combination of swimming, sunlight and cold water immersion. “If I do those three things, I’m gold.”

In the original Hapa Project, participants’ responses ranged from whimsical to profound. A memorable submission from a fifth-grade boy read, “A very littel (sic) boy that has no friends.” “He nailed the human condition,” Fulbeck said. “At some point, we’ve all been the blank in the blank. This kid just had the bravery to say it.”

The Hapa Project’s interactive installation at the Japanese American National Museum in 2018 quickly filled with visitor’s photographs and handwritten statements, surging past capacity on opening night and growing beyond its original space. “People started going right past my images, straight to these,” Fulbeck said. “It was a compliment and an insult at the same time, but exactly what I’d hoped would happen.”

Through revisiting participants decades later, Fulbeck emphasizes a deeper narrative around identity and self-acceptance. The portraits are markers of physical change but also of emotional and cultural evolution.

As the new exhibition opens, Fulbeck envisions its broader impact: “This isn’t just my project anymore. It’s always depended on others. It’s not about photographs on a wall; it’s about every individual who participated, every idiosyncrasy or story they shared. It’s about people feeling seen. Whether you’re five or 50, you look at these faces and realize you’re not alone.”