Japanese artist Tomiyama Taeko’s critique of imperialism

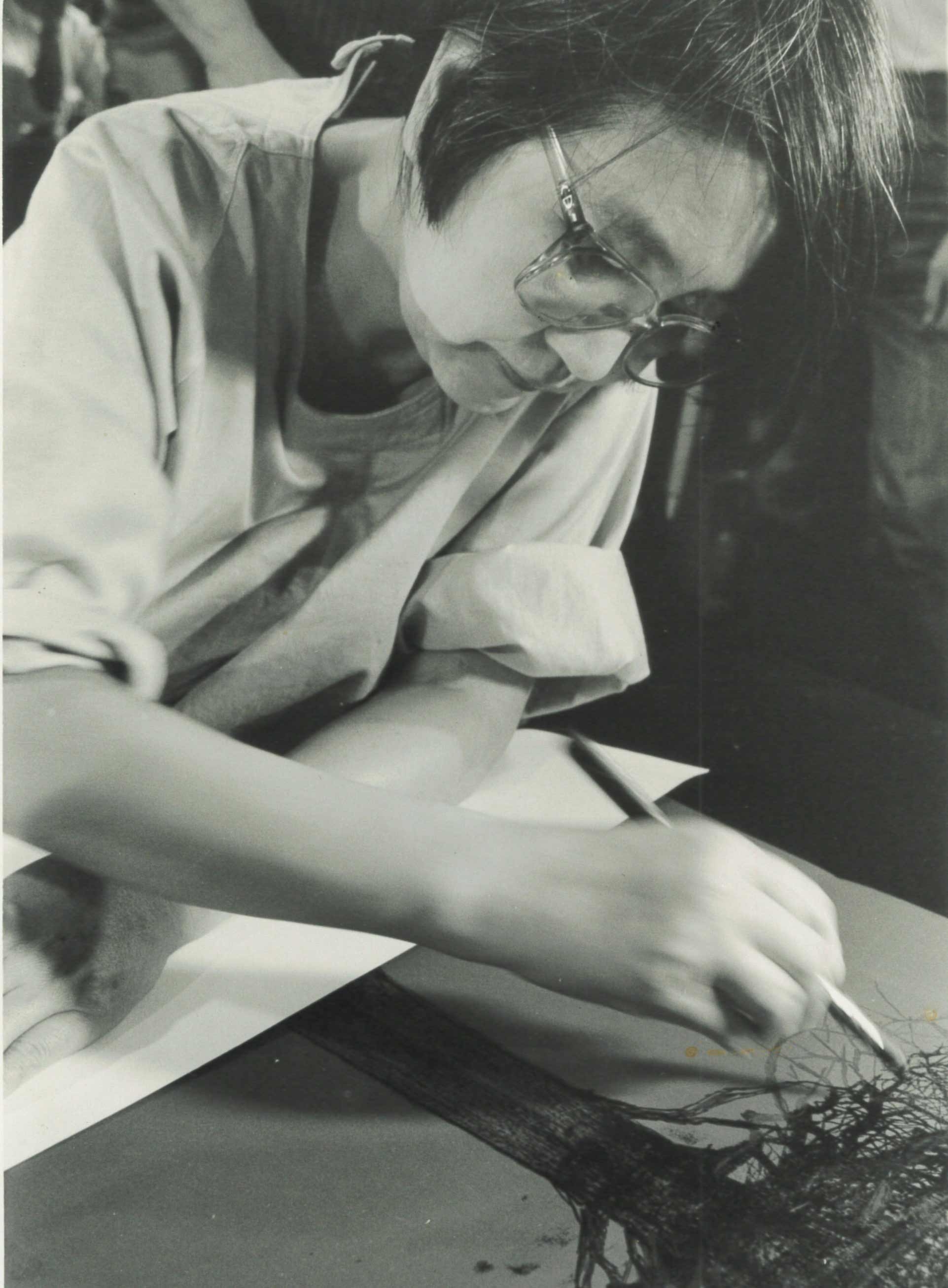

Japanese artist Tomiyama Taeko (1921–2021) might have remained a lesser-known figure, her work overshadowed by the tumult of colonialism and war that shaped her life. Yet her art — bold, evocative and politically charged — found recognition abroad, particularly in Korea, even as it remained underappreciated in Japan due to cultural taboos and her vivid critiques of imperialism.

Now, her groundbreaking series “Hiruko and the Puppeteers: A Tale of Sea Wanderers” is poised to reach new audiences. Thanks to a major gift to UC Santa Barbara’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum (AD&A), the series will make its U.S. debut, offering a profound exploration of history, imperialism and environmental stewardship. Tomiyama spent her youth in Japanese-occupied China before returning to Japan in 1938 to study art, her life experiences fueling a body of work that continues to resonate with contemporary themes of justice and memory.

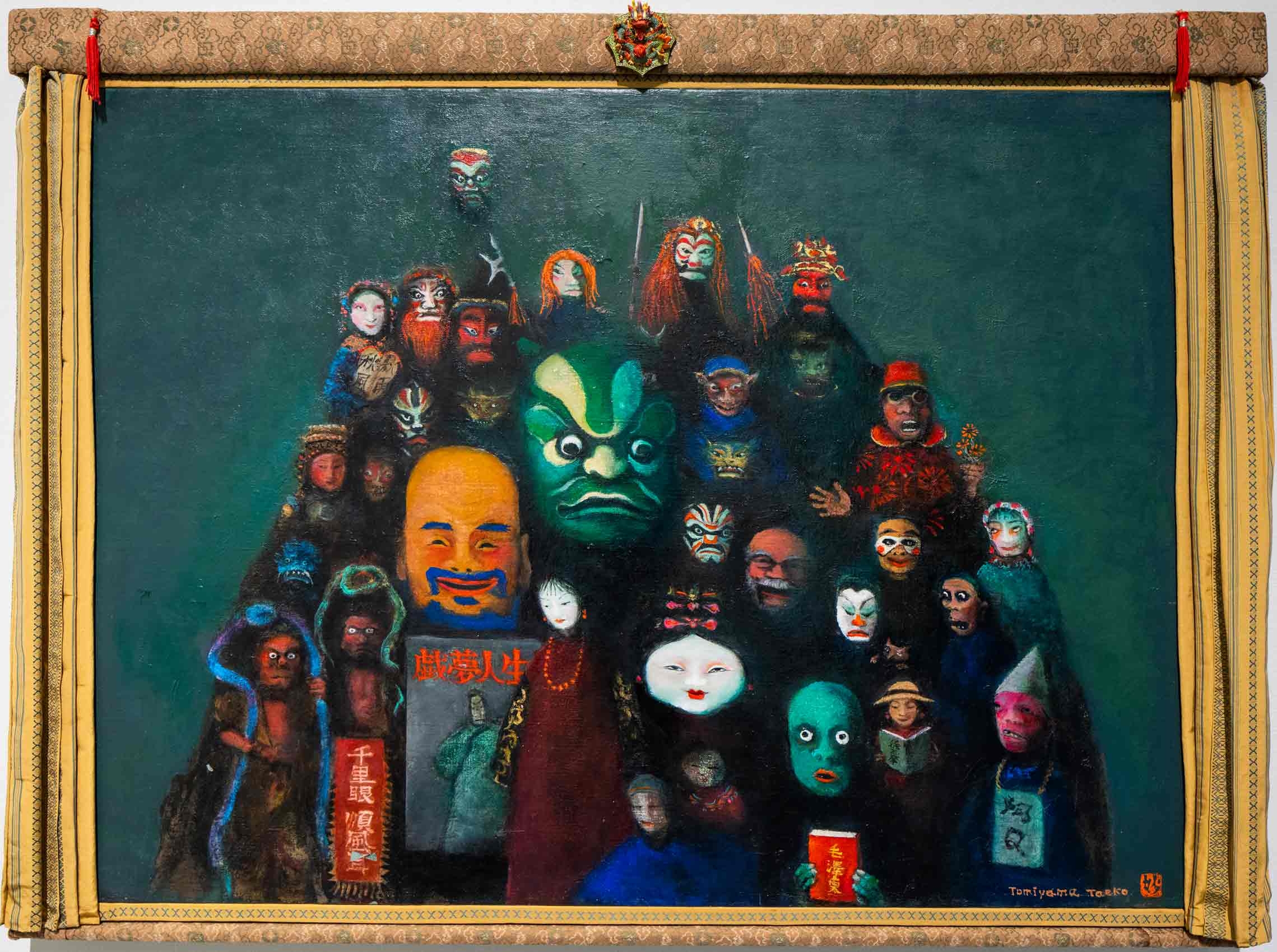

“She was unapologetically ahead of her time,” said the exhibition’s curator Gabriel Ritter, director of the AD&A Museum. “Tomiyama’s work champions democracy, gender equality and ecological consciousness, often confronting subjects still considered taboo in Japan.” The exhibition “Tomiyama Taeko: A Tale of Sea Wanderers” (Jan. 18–April 27) brings together 28 works from the “Hiruko” series, marking the largest collection of Tomiyama’s work outside Asia.

Born in 1921 in Kobe and later residing in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, Tomiyama witnessed firsthand the consequences of imperialism and war. These experiences informed her critique of colonialism, capitalism and environmental destruction. In her “Hiruko” series, she weaves these themes pictorially into a narrative that begins with ancient Japanese mythology — Hiruko, the “leech child,” cast out to sea — and transitions to a stark critique of Japan’s colonial history and its impact on the Pacific. Layered with symbolism, the series features collages and paintings teeming with seashells, skulls, imperial flags and army helmets, a surreal reminder of what lies submerged yet unresolved beneath the ocean’s surface.

In an earlier painting, “At the bottom of the Pacific” (1985), Ritter described an “eerie menagerie of seashells — but as you look closer — there’s also skulls, army helmets, Japanese imperial flags, and you start to get a sense that this is not just a surrealist painting about a kind of other world potentially under the sea, but something more sinister that has sunk to the bottom and is out of sight, but has not disappeared.”

Throughout her career, Tomiyama used diverse media to amplify her message. In addition to painting and printmaking, she collaborated with composer Yuji Takahashi to create multimedia slideshows, combining her visual art with evocative musical scores. One such project highlighted the 1980 Gwangju Uprising in South Korea, depicting the brutal government crackdown on pro-democracy protesters. Ritter first encountered these visceral works during the Yokohama Triennale in 2024, where they left a lasting impression. “Even in Japan, visitors would question if such bold, anti-imperialist work could come from a Japanese artist,” Ritter recalled.

The journey to bring Tomiyama’s work to UCSB began with a serendipitous connection: her family sought academic institutions willing to preserve and promote her legacy. Ritter’s research into Japanese surrealism and avant-garde movements aligned with Tomiyama’s themes, as did UCSB’s commitment to interdisciplinary inquiry. Collaborating with faculty from the Departments of East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies, Religious Studies, and History, Ritter found researchers were interested in the collection, adding fuel to securing the acquisition and ultimately in developing the exhibition.

Crucially, history doctoral student Hayate Murayama — who specializes in modern Japan and war memory — contributed to the project as a curatorial research assistant. “Hayate’s insights into Tomiyama’s life and work were invaluable,” said Ritter. Their joint effort underscores the exhibition’s role as both a cultural event and a teaching resource, fostering dialogue on themes ranging from gender and labor to ecological resilience.

“Tomiyama’s art invites us to rethink history through the eyes of those often left out of its narratives,” said Murayama. “Tomiyama’s work encourages audiences of all ages to explore the rich cultural connections and traditions united by the Pacific — connections that have been disrupted by imperialism and the profit motives of modern times,” added Murayama, whose Ph.D. advisor is Kate McDonald, an associate professor of history and director of the UCSB East Asia Center.

For Ritter, Tomiyama’s art offers more than historical critique; it’s a call to action. “The ocean, in her work, becomes a metaphor for humanity’s shared past and future,” he said. “It’s a reminder of the environmental stakes we face today.”

That resonance is particularly poignant at UCSB, situated on the Pacific coast and home to groundbreaking environmental research. The exhibition connects Tomiyama’s cautionary narratives to local histories like the birth of Earth Day in Santa Barbara.

“Tomiyama Taeko: A Tale of Sea Wanderers” represents a vital addition to UCSB’s artistic and intellectual community. As the largest U.S. exhibition of her work to date, it not only honors Tomiyama’s legacy but also invites viewers to reflect on the enduring consequences of imperialism and the urgent need for environmental and social justice.

Organized with the support of the AD&A Museum Council and UCSB’s Division of Humanities and Fine Arts, the exhibition is a testament to the power of art to challenge, inspire and transform. It opens a new chapter for Tomiyama’s legacy, one where her visions of justice and equality continue to resonate across oceans and generations.