Too much screen time — particularly related to social media use in kids, teens and young adults — is a major concern in modern society. Smartphones are ubiquitous. Social media is enticing. And the impulse-control and decision-making capacities in young brains are not yet fully developed.

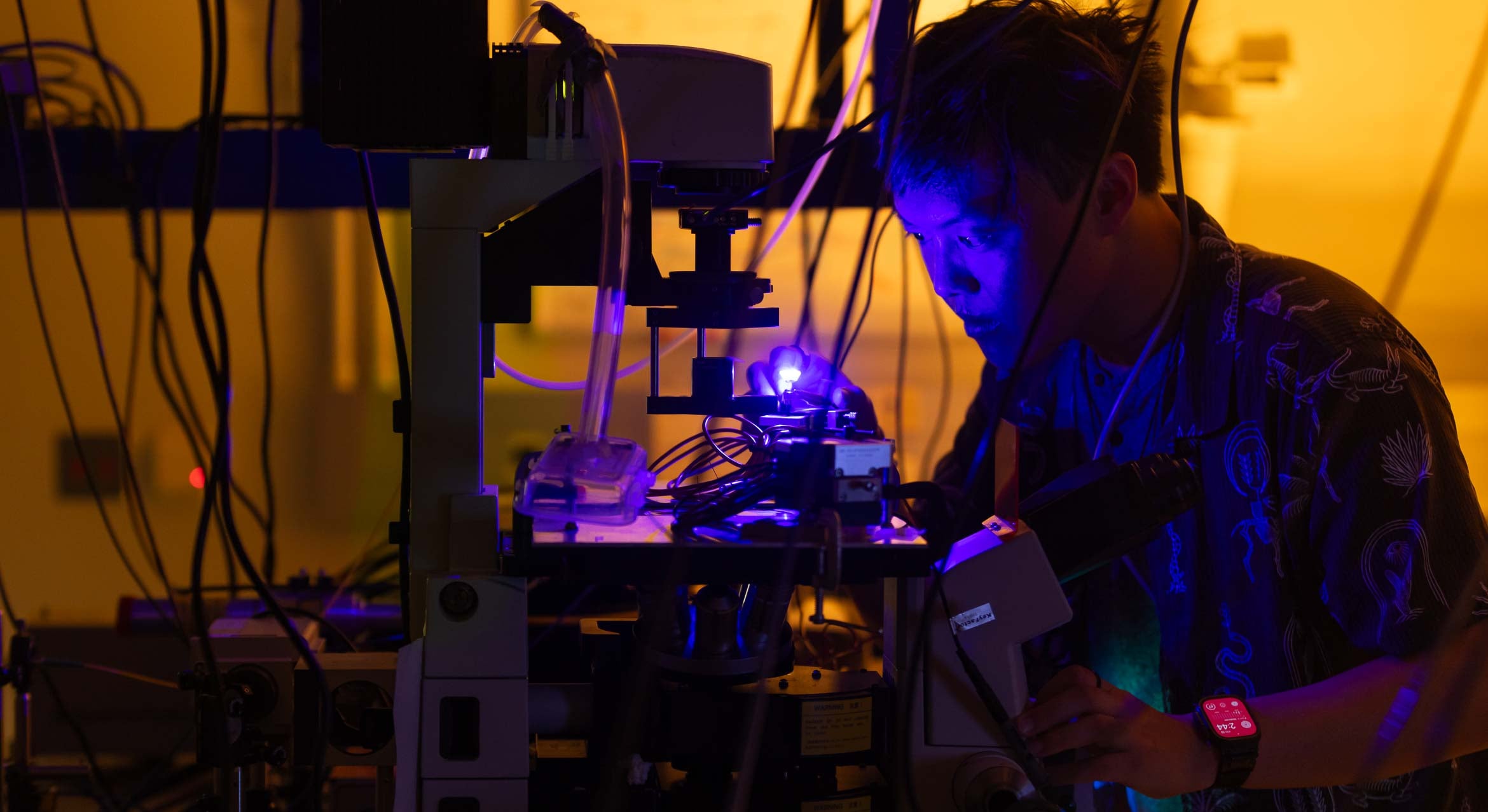

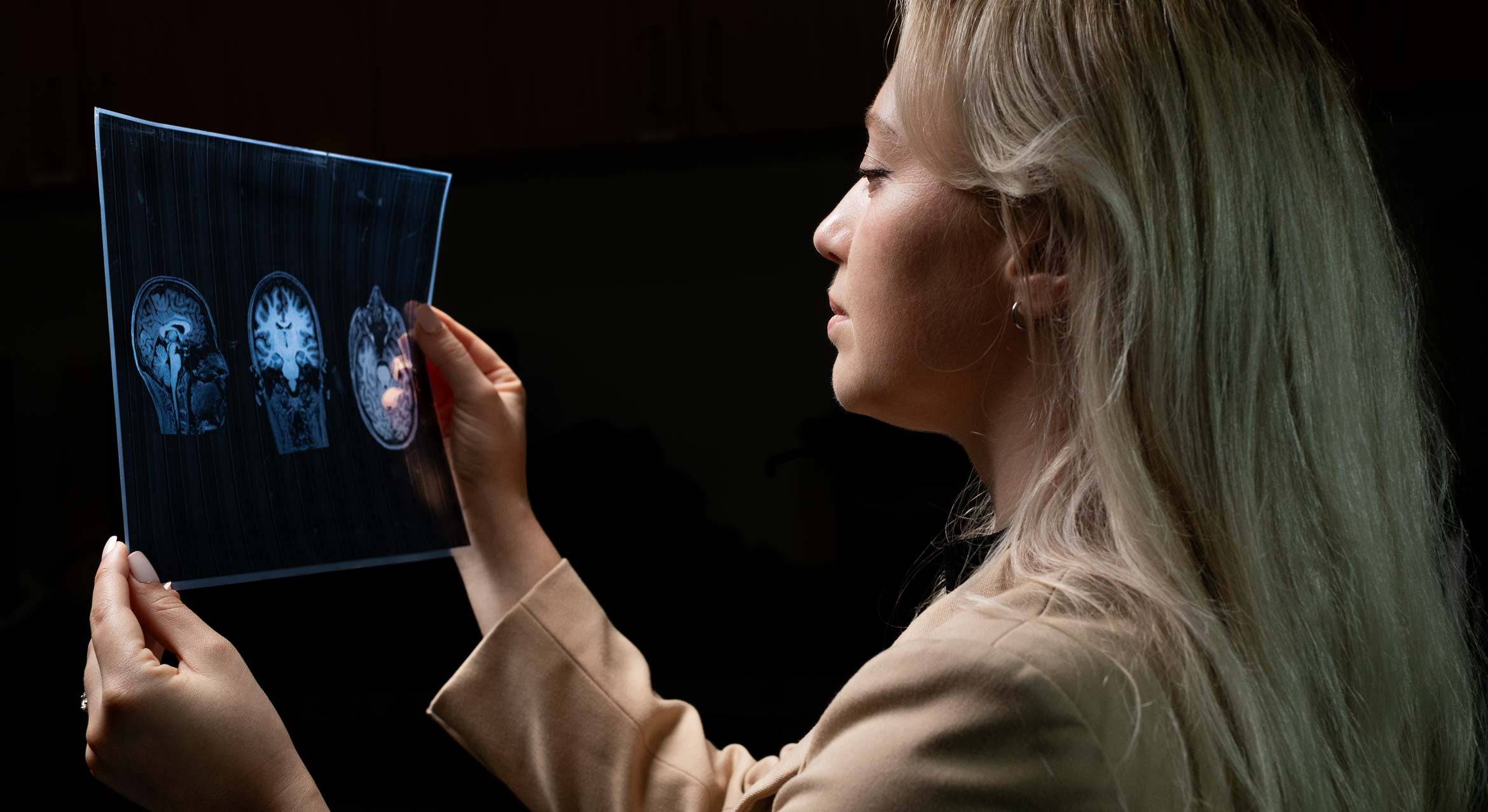

While social media addiction hasn’t been officially recognized as a mental health condition, it shows up in brain scans, according to Kylie Falcione, a graduate student in the Department of Communication and professor René Weber's Media Neuroscience Lab at UC Santa Barbara.

"The neural mechanism looks the same in the brain whether someone has a gaming disorder, is addicted to social media or gambling, or struggles with substance use," Falcione said.

In a recent gaming addiction study under review at the journal NeuroImage, Falcione and Weber found a pattern of reinforcement between gaming disorder and brain dysfunction within the reward system. This suggests that developing a gaming disorder changes how the brain processes rewards, creating a self-reinforcing cycle, she explained — brain dysfunction leads to hypersensitivity to rewards, which in turn increases disorder symptoms. Comparative imagery suggests that the same could hold true for social media addiction, as well.

For now, however, it’s certain that social media abuse “is a modern moral panic,” she added. As part of her doctoral work, Falcione has researched the history of media addictions, dating back more than 200 years. “This is not the first time we’ve seen something like this.”

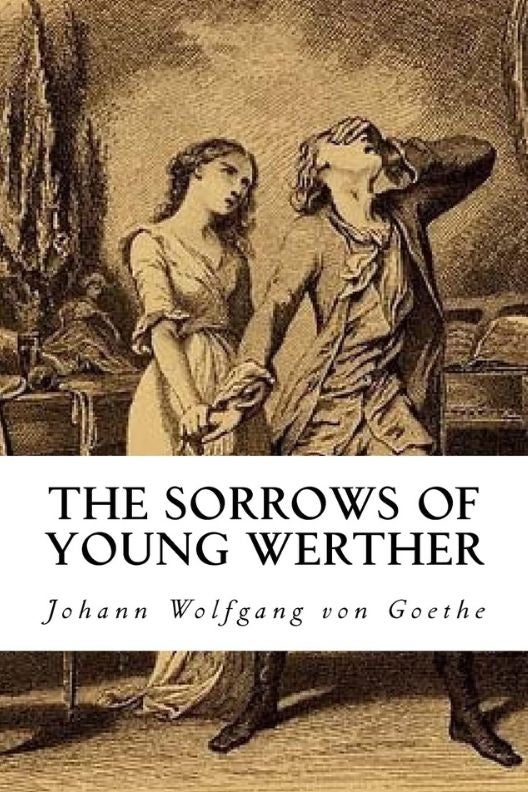

READING FEVER

In the late-18th century across England and Europe, the widespread popularity of reading novels was causing young people to hole up, shirk responsibility and act out immorally. Reading fever, as it was called, was also blamed for a spate of suicides among fans of Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s “The Sorrows of Young Werther,” first published in 1774. As the epistolary novel’s popularity grew, a sub-affliction — dubbed Werther Fever — presented mostly among young men, who dressed as the protagonist and, pistol in hand, killed themselves in the throes of unrequited love. The book was banned in Denmark and Italy; for other fictional offenders, a sin tax was floated as a general countermeasure.

RADIO

Much like the provocative novels 150 years prior, a new household technology in the 1930s took hold of young people. In the U.S., parents became exasperated with their kids’ obsession with listening to the radio, and blamed it for interfering with other interests, including reading, sports, playing music and participating in family conversations. Responding to content deemed overstimulating or inappropriate, such as the glorification of criminals in fictionalized dramas, parent activism prompted the National Association of Broadcasters to establish guardrails for children’s programming.

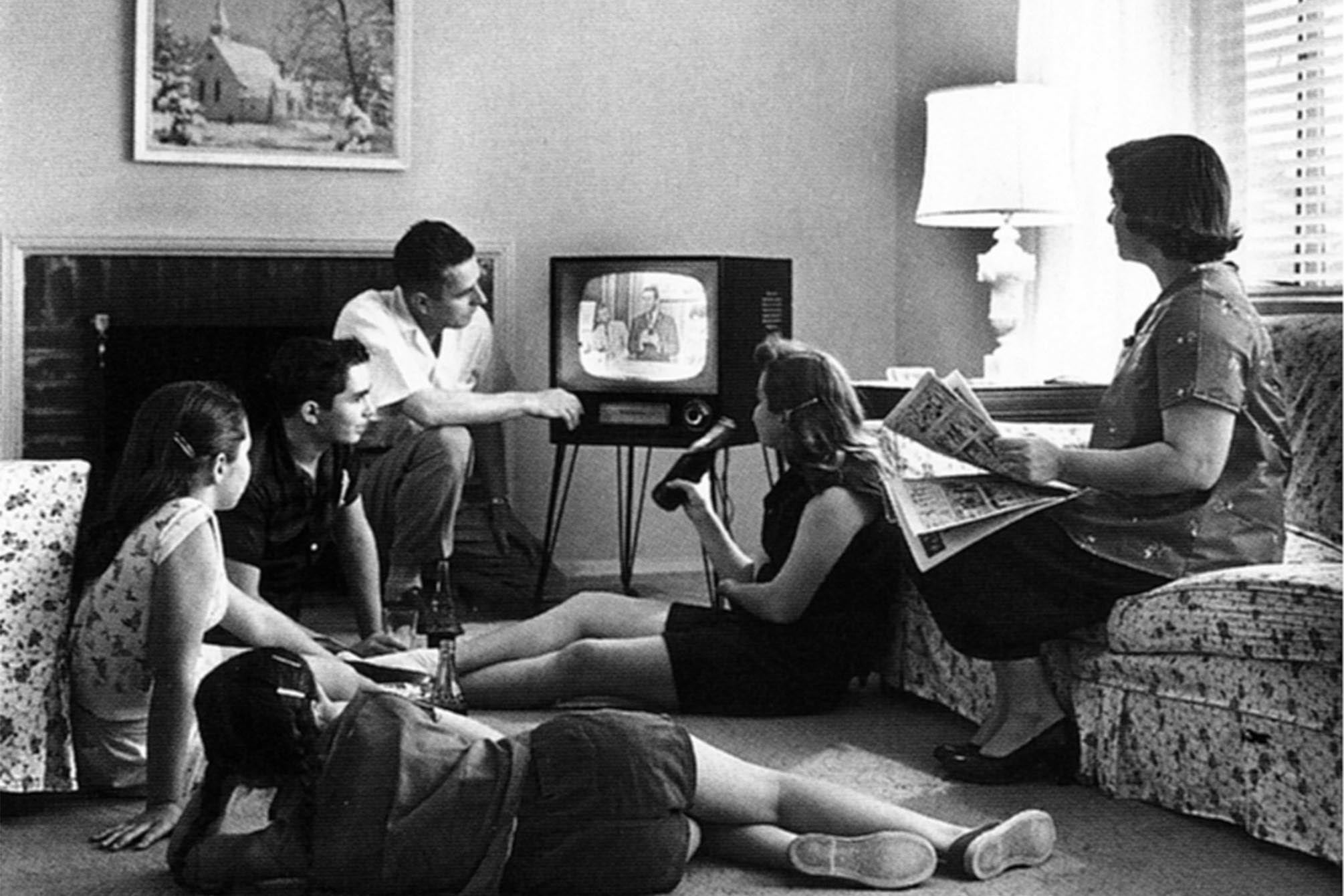

TELEVISION

Starting in the 1950s, televisions became standard in living rooms across the country. Not all shows were considered family friendly, however, and in 1969, the U.S. Surgeon General launched a three-year study of TV violence. The report’s summaries were mixed; in some cases, TV violence was found to promote aggressive behavior in some kids, but the study also put forth other considerations, including personality type, parental influence and the levels of violence in a young person’s surrounding community. “Television is only one of the many factors which in time may precede aggressive behavior,” the report stated. “It is exceedingly difficult to disentangle from other elements of an individual’s life history.”

VIDEO GAMES

Video game popularity first began its climb in the late 1970s, and has been on an upward trajectory ever since, particularly with the arrival of highly interactive online multiplayer platforms in the late 1990s. Research dating back to the early 1980s suggested that video game addiction was problematic among students. In 2018, the World Health Organization recognized gaming disorder as a mental health condition that intrudes detrimentally into an addicted gamer’s sleep, work, education and ability to foster and maintain relationships in real life, while also impacting memory, attention span and stress management.

SOCIAL MEDIA

Social media addiction hasn’t been officially recognized, Falcione said, “but it’s pretty clear – at least within the literature – that it seems to be transposable to the extent that all the criteria for gaming disorder also apply to a social media or smartphone addiction.”

There are three main criteria, she explained. The first is that the person feels a need to use that media more and more, which can build a tolerance similar to that experienced by drug addicts. Second, she continues, “there’s a salience that it becomes the most prominent thing in your life — it’s what you think about the most, it’s what you want to do the most, and even if you’re not on your phone, you’re thinking about it, craving it and choosing it over other activities that may need your attention.” The third criteria is that its use creates internal conflict or turmoil as it interferes with relationships or obligations to work or school.

“For teens and college students, when you see those grades drop, that’s a big signal that the media use is actually becoming detrimental,” Falcione said.

The original version of this article appeared in the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of UC Santa Barbara Magazine.