Warmer Water, Less Nutrition

As a foundational species, giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) is vital to the ecosystem of the temperate, shallow, nearshore waters where it grows. When the kelp flourishes, so do the communities that rely on the fast-growing species for food and shelter.

Giant kelp has proven resilient (so far) to some stressors brought on by climate change, including severe storms and ocean heatwaves — an encouraging development for those interested in the alga’s ability to maintain the legions of fish, invertebrates, mammals and birds that depend on it for their survival. But in a recent study published in the journal Oikos, UC Santa Barbara researchers reveal that giant kelp’s ability to take a temperature hit may come at the cost of its nutritional value.

“The nutritional quality, or the amount of nutrients in the kelp tissue seems to be changing,” said the study’s lead author Heili Lowman, a biogeochemist with the University of Nevada, Reno, who conducted this research as a Ph.D. student in the Department of Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology at UC Santa Barbara. “We found that those changes were associated or correlated with changing seawater temperatures. From a big-picture standpoint, that’s pretty important because there are a lot of things that rely on kelp as the primary food source.”

“I guess you could call it one of the more hidden effects of ocean warming,” said study co-author and UC Santa Barbara graduate student researcher Kyle Emery. “We haven’t necessarily lost kelp in places that have had these big temperature increases, but the kelp there has declined in terms of its nutritional content. So although it’s still there, it’s not able to provide the same function as when temperatures are lower.”

These findings of ocean warming’s hidden effects on kelp come from long-term data gathered at UCSB’s Santa Barbara Coastal Long-Term Ecological Research (SBC-LTER) site, which consists of several kelp forests located in the Santa Barbara Channel. Thanks to data collected over almost two decades, researchers have been able to track patterns of nutrient content, which fluctuate seasonally, and identify significant trends.

“The temperature of the seawater and nutrient availability are really closely coupled in the Santa Barbara Channel, and we’ve known that for some time,” Lowman said. Generally, the cooler temperatures bring nutrient-rich waters up from the deep, but during the warmer seasons, nutrients in the shallows and upper ocean — particularly nitrogen — become more scarce.

“Physiologically, kelp plants can’t store nitrogen for longer than a couple weeks, so whatever’s happening around them in the water they’re going to respond to very quickly because they need a constant supply of nitrogen to grow, and to continue to reproduce,” she said.

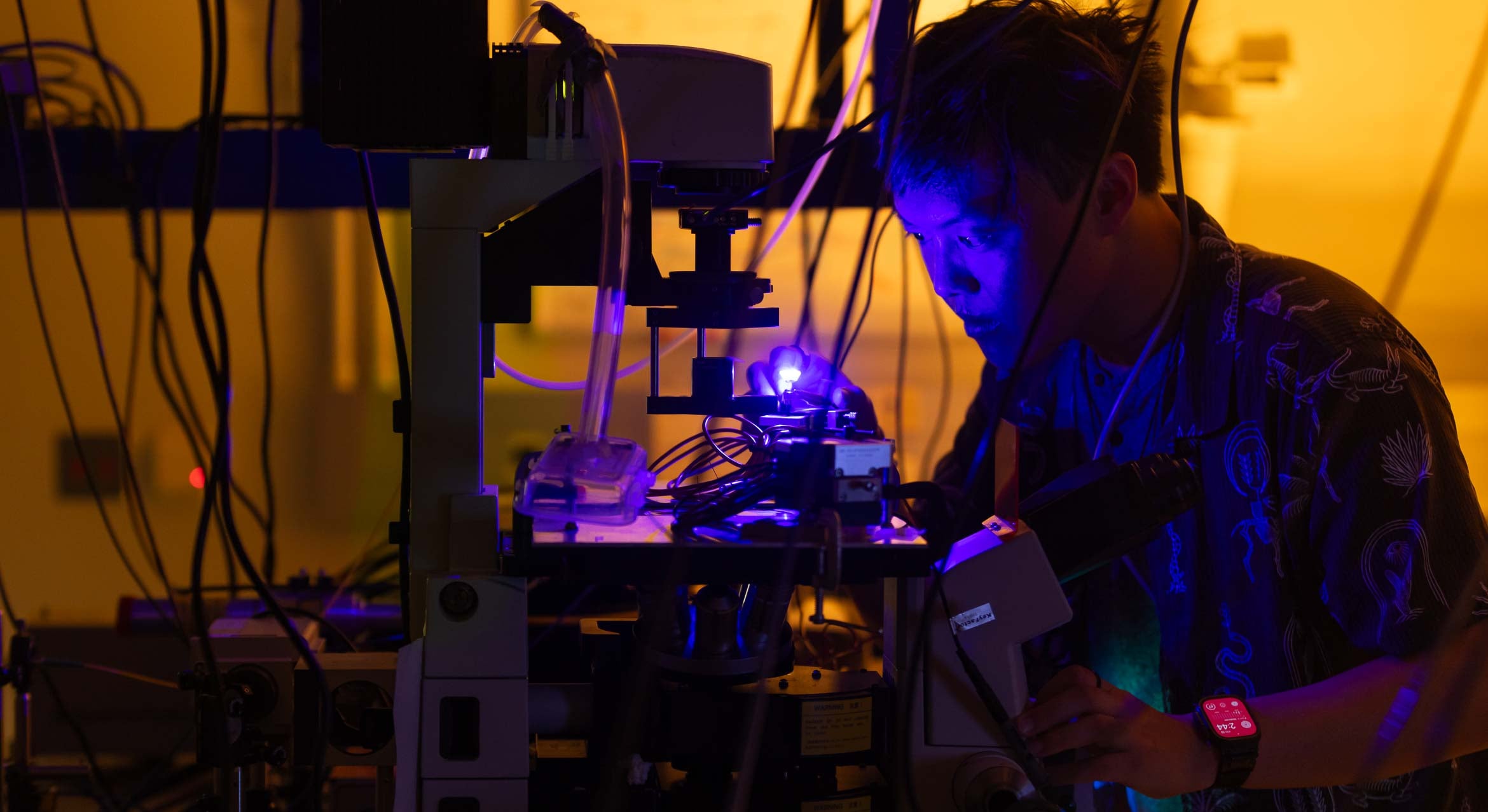

Knowing this pattern, the researchers then sought out how nutrient content might play out over a longer period of time, as ocean temperatures rose. They did so by looking at data from the primary productivity sampling that is conducted in the waters at the SBC LTER on a monthly basis.

“As part of that sampling, kelp blades are collected from these sites, brought back to the lab and then processed for carbon and nitrogen content,” Emery explained.

Over the 19-year period covered by the SBC LTER, according to the paper, nitrogen content of the giant kelp tissue declined by 18%, with a proportional increase in carbon content, according to the paper.

This apparent decline in nutritional content does not bode well for the consumers of kelp in and around the Santa Barbara Channel, which include sea urchins and abalone in the water, and intertidal beach hoppers and other invertebrates that consume the kelp wrack that washes up on the shore.

“As a result, urchins, for example, might go in search of a lot more kelp and that could cause a shift in certain places, potentially from a kelp forest to an urchin barren, if they’re just mowing down the reef looking for more food,” Lowman said. Animals that feed on kelp might also expend more energy trying to eat enough to fulfill their nutritional requirements.

While urchins have the ability to go searching for more food, Emery added, the consumers on the shore are stuck with what they get.

“If you have greater demand, but there’s not more kelp coming in, that poses a pretty challenging situation for them, whether it’s being underfed or through population declines,” he said.

In both cases, the effects could ripple out to the rest of the food web, the researchers said: Lower-nutrition kelp could mean smaller, fewer, perhaps less healthy beach hoppers, for instance, which would lead to less food for the shorebirds that eat them. In the water, less nutrition for urchins and abalone could mean less food for their consumers, including fish, lobster, sea otters and humans.

“Our results raise a lot of really interesting open-ended questions and suggest a lot of far-reaching effects,” Emery said.

Having explored the potential relationships of seawater temperature to nutritional content, the researchers are considering broadening the spatial scale of the study.

“The next step would be thinking about what all is playing into determining the nutritional content and then how might we then be able to predict it into the future,” Lowman said.

Research in this paper was conducted also by Jenifer Dugan and Bob Miller.