After years of searching, scientists at the Micro Booster Neutrino Experiment (MicroBooNE) have ruled out the possibility of the existence of a sterile neutrino, a hypothetical particle that had long been speculated as a solution to open questions in particle physics. Publishing their results in the journal Nature, the collaboration’s result narrows the field of possibilities that could explain one of today’s biggest puzzles in neutrino physics.

“Neutrinos are elusive fundamental particles that are difficult to detect experimentally, yet are among the most abundant particles in the universe,” said UC Santa Barbara assistant physics professor David Caratelli, who was the physics coordinator for the experiment when this analysis was carried out. Previous experiments have made observations that are at odds with what is known about this particle, he added, opening up speculation on a hypothetical fourth neutrino — a “sterile” neutrino. However, MicroBooNE’s latest results show that this hypothesis does not fit with its data.

Ruling out this hypothesis is a major milestone for the field, Caratelli said, energizing searches for new exotic particles while giving particle physicists a leg up on future, larger experiments that dive into the nature of neutrinos.

This research is supported in part by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation.

A neutrino puzzle

The Standard Model is a solid, self-consistent theory of the interlocking forces and particles that underlie the universe, and much of it has been proven experimentally. However, there are areas that continue to challenge scientists.

“We know that the Standard Model does a great job describing a host of phenomena in the natural world,” said Matthew Toups, Fermilab senior scientist and co-spokesperson for MicroBooNE. “And at the same time, we know it’s incomplete. It doesn’t account for dark matter, dark energy or gravity.”

One such gap in understanding is in the realm of neutrinos, which the model initially predicted to have no mass. However, a series of experiments in the latter half of the 20th century that measured neutrinos as they came in from outer space hinted that something odd was happening with these so-called “ghost” particles. Essentially, these experiments noted that certain neutrino “flavors” — they come in either electron, muon or tau flavors — were disappearing as they were traveling, leading scientists to conclude that these particles were oscillating between the flavors, changing their identities as they traveled.

“The only way this oscillation can happen is if neutrinos have mass,” Caratelli explained. “This is something that the Standard Model did not predict.”

Further investigations conducted in the 1990s at the Liquid Scintillator Neutrino Detector (LSND) at Los Alamos National Laboratory and the MiniBooNE experiment at Fermilab into neutrino oscillation turned up another puzzle: muon neutrinos oscillating into electron neutrinos in a way that is not possible with only three neutrino flavors. “The most popular explanation to these anomalies for the past 30 years has been a hypothetical sterile neutrino,” explained Justin Evans, a professor at the University of Manchester and co-spokesperson for MicroBooNE.

Compared to the three known neutrinos, which couple to their charged counterparts via the electroweak force, this hypothetical fourth neutrino would not couple to a charged counterpart via the weak force.

Enter MicroBooNE, a more sensitive detector built at Fermilab to observe with greater resolution these seemingly anomalous oscillations.

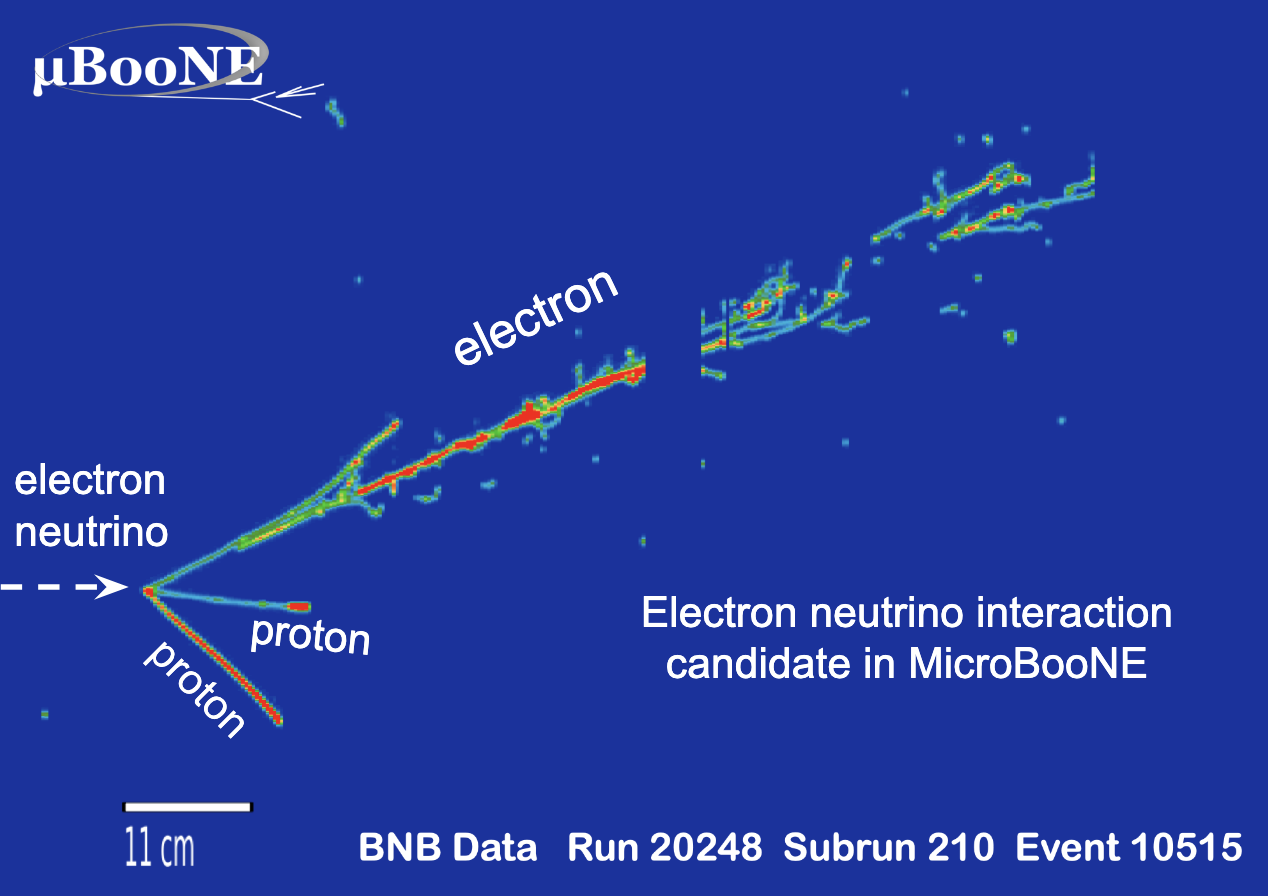

To investigate, the MicroBooNE collaboration took data from two neutrino beams at the Fermilab campus from 2015 to 2021. These beams direct neutrinos toward the MicroBooNE liquid-argon time projection chamber, an instrument that allows the researchers to observe neutrinos as they interact with the highly sensitive liquid argon inside the chamber.

“We produce neutrinos of one kind and place our detectors at optimal positions so that we could maximize the probability of finding this sterile neutrino,” Caratelli said. “In practice, what we did is produce muon neutrinos and if a sterile neutrino were to exist, we would see an appearance of electron neutrinos.”

They then measured how many electron neutrinos reached the detector, and tested the data against the rates they would get if there was a sterile neutrino, and also against the prediction if there wasn’t a sterile neutrino. “Basically, what we were looking for is the effect of the appearance of new electron neutrinos caused by this oscillation phenomenon.”

What they saw, Caratelli said, was consistent with no oscillations into a sterile neutrino, thus ruling out the existence of this hypothetical particle. This work followed an earlier result led by the UCSB group published in Physics Review Letters in the summer of 2025 which ruled out an excess of electron neutrinos.

A 'paradigm shift'

While the collaboration has closed the door on the sterile neutrino hypothesis, the mystery unearthed by LSND and MiniBooNE remains, one that the scientists are eager to dive into with more, and more powerful detectors.

“I think it’s a bit of a paradigm shift for us,” Caratelli said. After ruling out the roughly 30-year-old sterile neutrino hypothesis, the researchers look forward to investigating a much broader landscape of theories that could explain this anomaly and more generally address open questions in particle physics, including uncovering the nature of dark matter.

“We have a much more varied menu of options that we’re investigating,” Caratelli added. And to do this, the researchers also have the benefit of the technology and methods they developed and perfected in their work with MicroBooNE to take to multi-detector approaches.

One such option looks into whether photons, from a possible mis-modeled background or alternative new physics explanation, may be responsible for these anomalies. UCSB physics professor and MicroBooNE collaborator Xiao Luo recently released a first analysis that begins to investigate this new hypothesis. The broader Short Baseline Neutrino program at Fermilab, to which the UCSB team contributes, will be able to study these questions in even greater detail in the coming years.

Meanwhile, preparation and construction are underway for the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE). Located a mile underground at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota, the particle detector, which will be the largest of its kind ever built, will receive the world’s most intense beam of high energy neutrinos fired through the ground from Fermilab, 800 miles away.

“MicroBooNE is big — it’s the size of a school bus. But DUNE is football field-scale,” said Caratelli, who is a member of the DUNE collaboration. Its sensitivity, precision and the amount of data it will generate could give scientists insights not just into neutrino oscillations, but also other mysteries of physics that neutrinos are associated with, such as why the universe has more matter than anti-matter.

One of the key things that MicroBooNE did was give us all confidence and teach us how to use this technology to measure neutrinos with high precision,” Caratelli said. “What we learned with MicroBooNE on how to analyze the data that comes to the detector all directly applies to DUNE.”