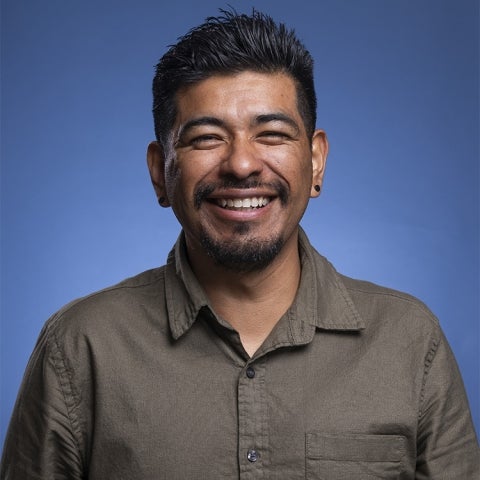

Born in Los Angeles to Guatemalan parents, Giovanni Batz was the first in his family to attend college. Studying political science at California State University Northridge, he started researching politics and war in Central America and the Maya diaspora. The work became the basis of his masters in Latin American studies and doctoral research in social anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin.

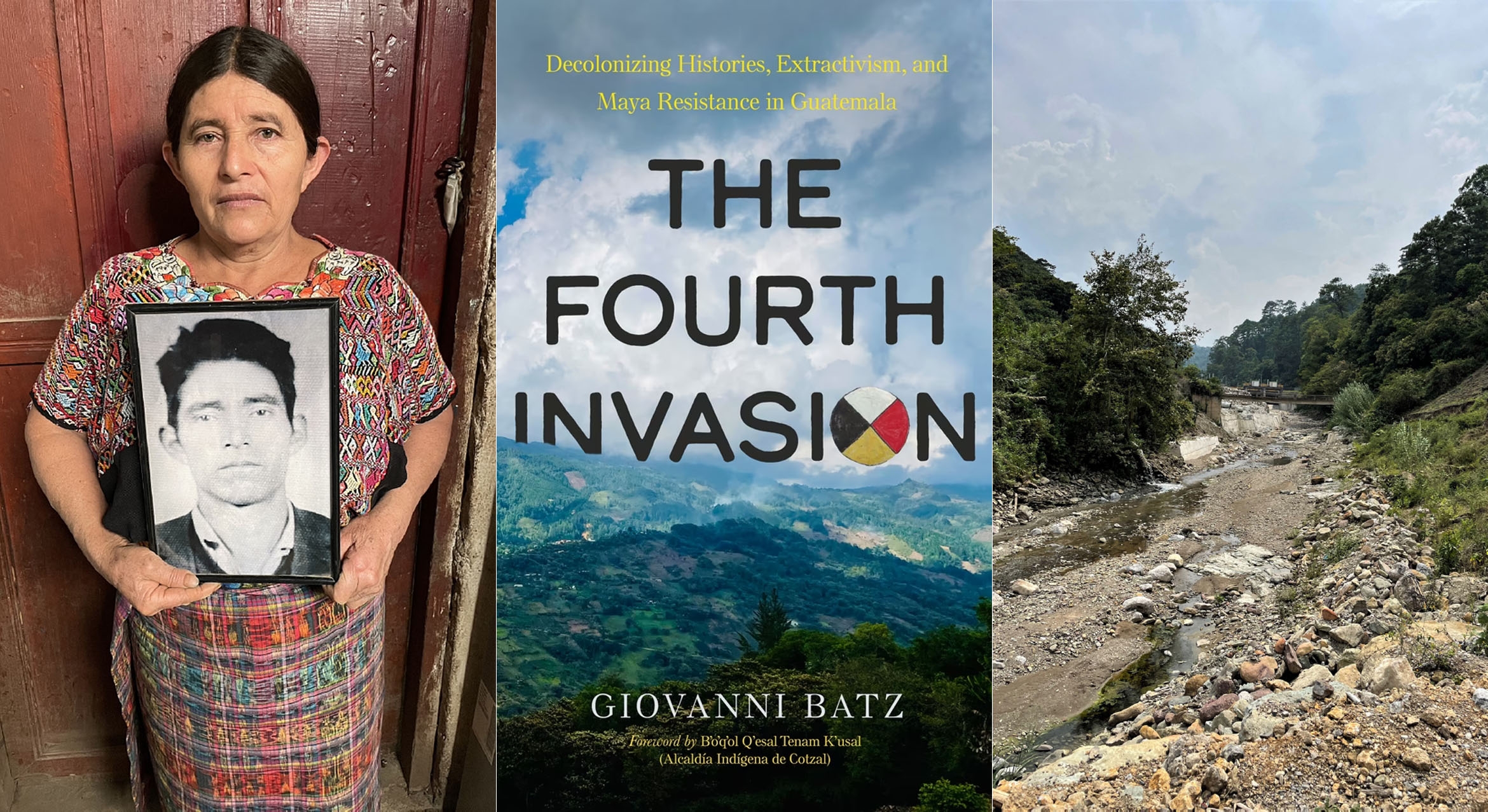

And now, culminating more than a decade of ethnographic research, it’s the basis of his new book, “The Fourth Invasion: Decolonizing Histories, Extractivism, and Maya Resistance in Guatemala” (University of California Press). In it, Batz, today an assistant professor in the Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies at UC Santa Barbara, argues that present-day mining and hydroelectric projects, among other extraction-based industries spearheaded by foreign companies, are a continuation of colonial invasions that have displaced and destroyed the country’s Indigenous territories since 1524.

Batz’s work is “critical for understanding how Guatemalan Indigenous peoples have encountered multiple invasions for more than five centuries, including by the contemporary extractivist corporations that are generating tremendous profits as well as massive environmental destruction,” said colleague Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval, a professor of Chicana and Chicano studies at UCSB. “Indigenous people, particularly Ixil communities, have organized and resisted. This movement parallels other Indigenous movements across the Americas that are focused on environmental and social justice.”

On a research fellowship in 2011, Batz traveled to the town of Cotzal, located in the Western Highlands in Guatemala, where the Ixil Maya community was fighting the construction of the Palo Viejo hydroelectric plant being built by Enel Green Power, a corporation based in Italy. Locals referred to the project and other extraction-based industrialization as the “new invasion” or “fourth invasion,” Batz said. The Central American county’s first three invasions, he explained, were the Spanish colonization of the early 16th century, the rise of the plantation economy during the late-19th and early-20th centuries and the state-sponsored genocide during the Guatemalan Civil War (1960-1996).

“I started learning about their struggles, including their history and the genocide that they had experienced,” Batz said. “I did my research there (in Cotzal) for two months, and I asked if I could come back the following year to present my results.” For the next 12 years, Batz made return trips to Guatemala, including 27 months of field research between 2013–2015.

“I have a natural curiosity about learning, and I wanted to explain the reality that I lived in at that point in time,” he added. “And I had also developed a political commitment with the people there.” During his project he regularly spoke and collaborated with the ancestral authorities of Cotzal.

“How do you consult communities about these extractivist industries, and what is the role of scholars in extracting knowledge?” he asked: “As scholars, we sometimes make our careers off of other people’s stories, right? How do I not replicate the extractivist violence that I’m critiquing? How do I develop a different research process? At every stage I kept that in mind. These injustices continue today, and it's not going to end anytime soon. So it’s not just an academic exercise for me. And the fact that the ancestral authorities vouched for the book and wrote the foreword for me is really important.”

Batz said that, over the years, the most rewarding part of his research and resultant book projects was earning confianza (trust) and building kinship with the communities he worked with. At the same time, he was recovering his own Maya roots, even something as seemingly straightforward as walking in the mountains in Guatemala, he remembered.

“At first I would wear my Chuck Taylors because I’m an urbanite from LA. I was slipping and falling and learning how to pick myself up. That was very symbolic in terms of how I try to carry myself today. Learning to walk, everyone is going to trip and fall, right? You just have to get up.”

A free ebook version is available through UC Press’s open access publishing program, Luminos.