William Davies King was a math-and-science kid in boarding school when a reading assignment in a literature class opened his young mind to the power of the arts. From that point on, his life tracked in a new direction.

His homework on that fateful evening was to start reading the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Long Day’s Journey into Night” by American playwright Eugene O’Neill. King, who was 14 at the time, finished it in one sitting. “The play awakened me to what art can do, the power it has to bring meaning and sympathy to the painful reality a person might encounter within a family,” he said. “I reread it the next evening, and by the time I graduated from high school, I had read all of O'Neill’s plays and a biography and I had seen the Sidney Lumet film of the play and a community theater production, and I decided to go to Yale where the O'Neill papers were archived.” Those were just King’s first steps toward a four-decade career in theater history with frequent revisits to the work of the 1936 Nobel Prize winner.

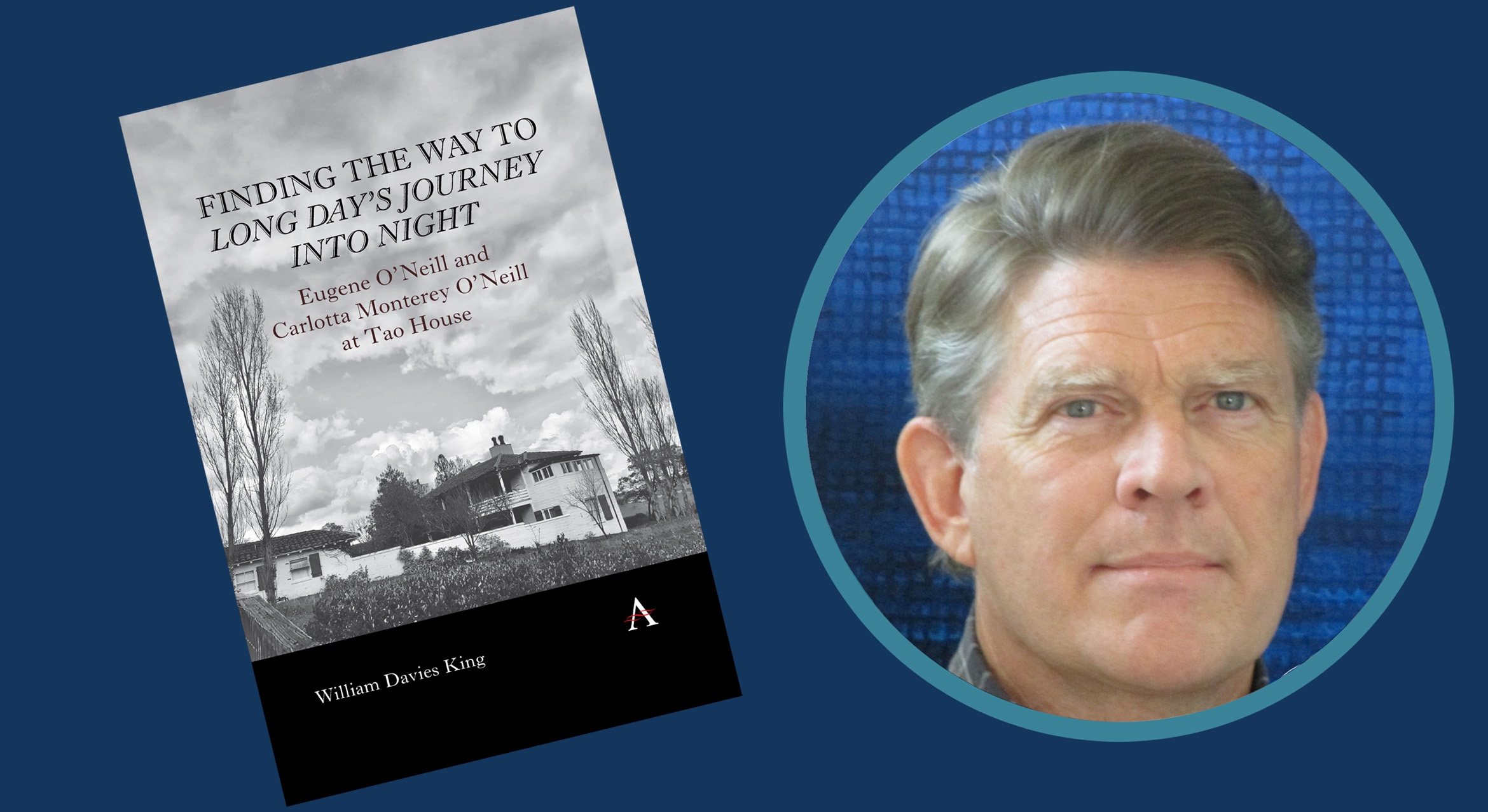

King now returns to the origin point of his deep dive into O’Neill’s life and letters with the September publication of “Finding the Way to 'Long Day's Journey Into Night': Eugene O’Neill and Carlotta Monterey O’Neill at Tao House” (Anthem Press, 2024). In the 362-page hardcover book, King examines the play — widely revered as a masterpiece of 20th century drama — in the context of the Taoism-inspired California home where it was written, historical circumstances leading up to World War II and the playwright’s fractious marriage to Carlotta Monterey O’Neill, his third wife. The book also serves as a professional swansong of sorts for King, a distinguished professor of theater and dance at UC Santa Barbara, where he has been teaching since 1987; King is planning to retire next year.

Taking a “fresh journey” into the autobiographical drama as it confronts O’Neill’s family tragedy circa 1912, King also argues that the play originated equally as a reflection of the time and circumstances of its writing some 30 years later and was widely enriched by the couple’s marriage and homelife. “Tao House,” their home on the edge of a wilderness preserve in Northern California, is now a National Historic Site. King’s book draws from vast quantities of documentary materials — particularly the diaries kept by the playwright and his wife — to bring O’Neill’s life at that time into focus.

Such sources helped King produce what he considers “the most granular and at the same time the most far-reaching inquiry into how this quintessential play was written — and almost not written — and how it came into the world.” He argues that there is a reason why this quintessential American drama could only be written at the endpoint of O’Neill’s career and in the ecological and ideological environment of California, which makes it especially pertinent to teach to University of California students.

“The play is very much alive today,” King added, “and it has become an essential challenge for all the great actors, starting with Fredric March, Katherine Hepburn and Jason Robards, and more recently Vanessa Redgrave, Jessica Lange and Gabriel Byrne. I have seen 17 different versions, most recently one with Brian Cox, who plays Logan Roy in HBO’s ‘Succession,’ this past March in London. Each one has reopened the play to the present.”

The book is laid out in a non-traditional design, juxtaposing the couple’s diary entries on the left side of the inside seam and King’s written chapters to the right. “As the culminating book of my academic career, I was reluctant to make compromises,” he said. “The result is a book that matches my vision, using a bicameral structure to capture the nexus of chronicle and history, literature and performance.”