Recasting the architecture of empire

Ask any undergraduate or high school student and they will tell you empires are big and vast territorial entities.

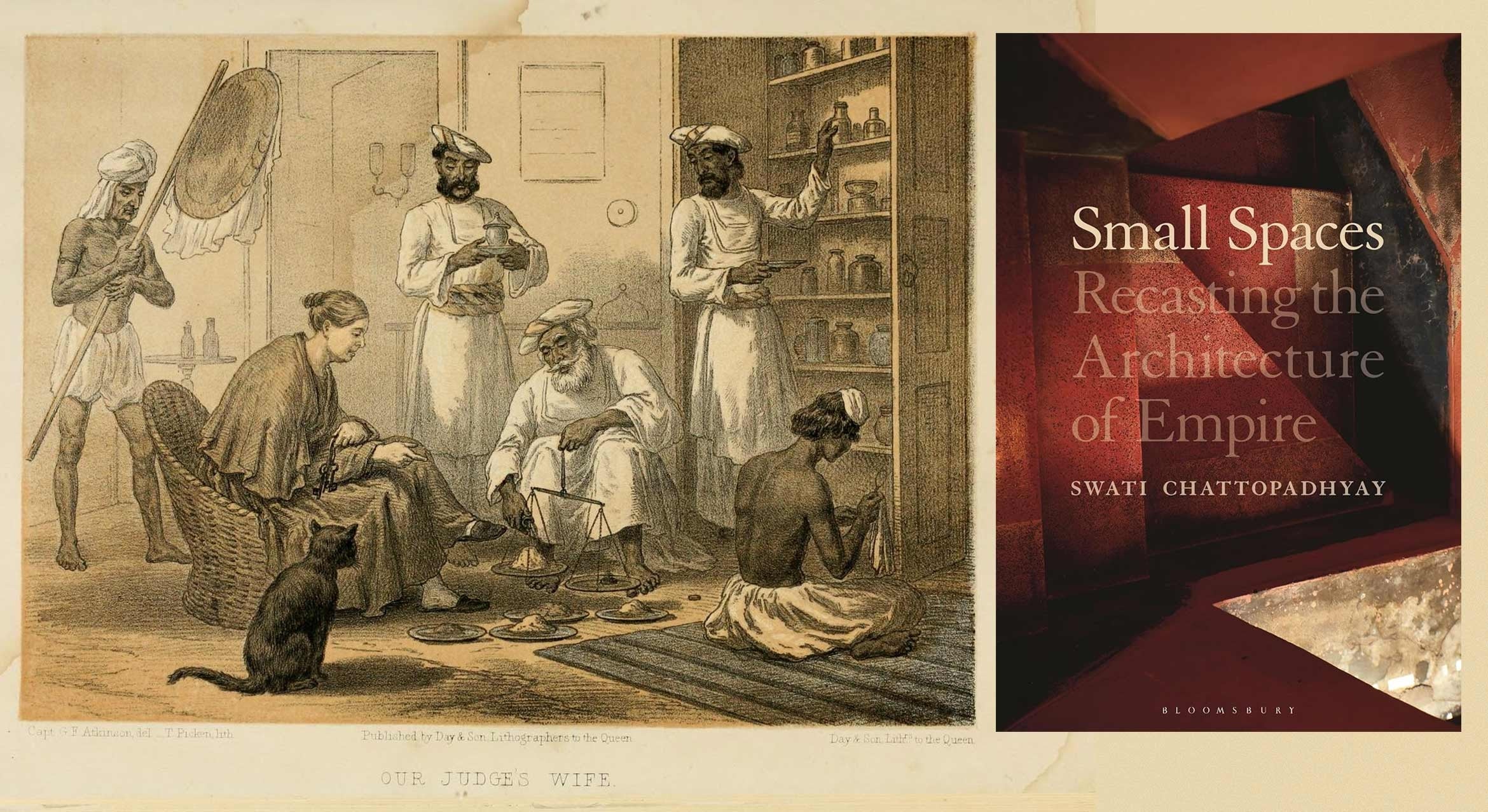

But that’s overlooking a lot of what makes up an empire, and how empire’s bigness is construed, according to architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay, a professor of architecture and urban history at UC Santa Barbara. Her latest book, “Small Spaces: Recasting the Architecture of Empire” (Bloomsbury 2023), takes a granular approach to the architecture of the British Empire, paying close attention to what has been overlooked in histories of colonialism and empire — particularly, spaces that have been deemed insignificant because of their small size, their marginal location or the minor role they seemingly played in the larger social and political scene.

“What fascinated me is that most of the spaces — and that could be storage spaces, kitchens, verandahs, servants’ quarters — never really figured in narratives of empire, even though they were essential to its everyday functioning,” said Chattopadhyay, who for years jotted down her notes in the margins of her research into the British empire’s big problems, key players and major colonial cities like Calcutta and New Delhi. “What is interesting is that some of these spaces such as warehouses and verandahs could be dimensionally large, so not ‘small’ in the conventional sense; but they were not considered suitable sites for launching stories. They were imagined as adjunct spaces, secondary or tertiary in importance to the formal spaces of gathering, ceremony and reception. To work around this scalar and dimensional prejudice of empire, you have to shift vantage,” she noted.

In her book, Chattopadhyay recalibrates the terms by which we approach the history of the British empire by focusing on the small spaces that made the empire possible. Taking the British empire in India as her primary focus, she discusses a series of architectural spaces, objects and landscapes to narrate untold stories of marginalized people — the servants, women, children, subalterns and racialized minorities — who held up the infrastructure of the empire. In doing so, “Small Spaces” is an important new approach to architectural history: an invitation to shift our attention from the large to the small scale.

Exploring an array of overlooked places and spaces, from cook rooms and slave quarters to outhouses, godowns, medicine cupboards, rooftop terraces and bookshelves, Chattopadhyay reveals how and why these kinds of minor spaces are so important to understanding colonialism. These sites of labor and recreation contributed to long-distance trade, became related to foodways and famines, and enabled landscape imagination and collecting practices.

By discussing the power dynamics and connections to empire in these spaces, as well as the importance of shifting the vantage point and centering the perspectives of disenfranchised populations, Chattopadhyay’s “Small Spaces” offers a new methodology for telling, constructing and understanding historical narratives.

The book is a paradigm-breaking account of the minor, overlooked spaces of empire, for anyone wishing to decolonize disciplinary practices in architectural, urban and colonial history.