Artist Lisa Jevbratt explores history of invasive plants through textiles and data visualization

Despite their casting as problem species, invasive plants often hold deep ties to historical events and customs. A yearning to better understand their relationship to one specific ecosystem, the land and human life led artist Lisa Jevbratt to study their color and material properties.

“We are dyeing wool with dyestuff from invasive and non-native plants growing on Santa Cruz Island in the Channel Islands archipelago in California, investigating the complex and intertwined influence humans have on our ecosystems, and the aesthetic, emotional, magical and medicinal interrelationships between humans, plants and color,” said Jevbratt, aUC Santa Barbara art professor. With the spun wool, Jevbratt and her collaborator Helén Svensson of Stockholm, Sweden, weave shawls, some of which are on view in “Interlopings — Experiencing the Warp and Weft of Ecological Entanglements” at Chrisman California Islands Center in Carpinteria until October. (Many were previously on view in “Interlopings – Colors in the Warp and Weft of Ecological Entanglements” at the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, December 2022 to April 2023).

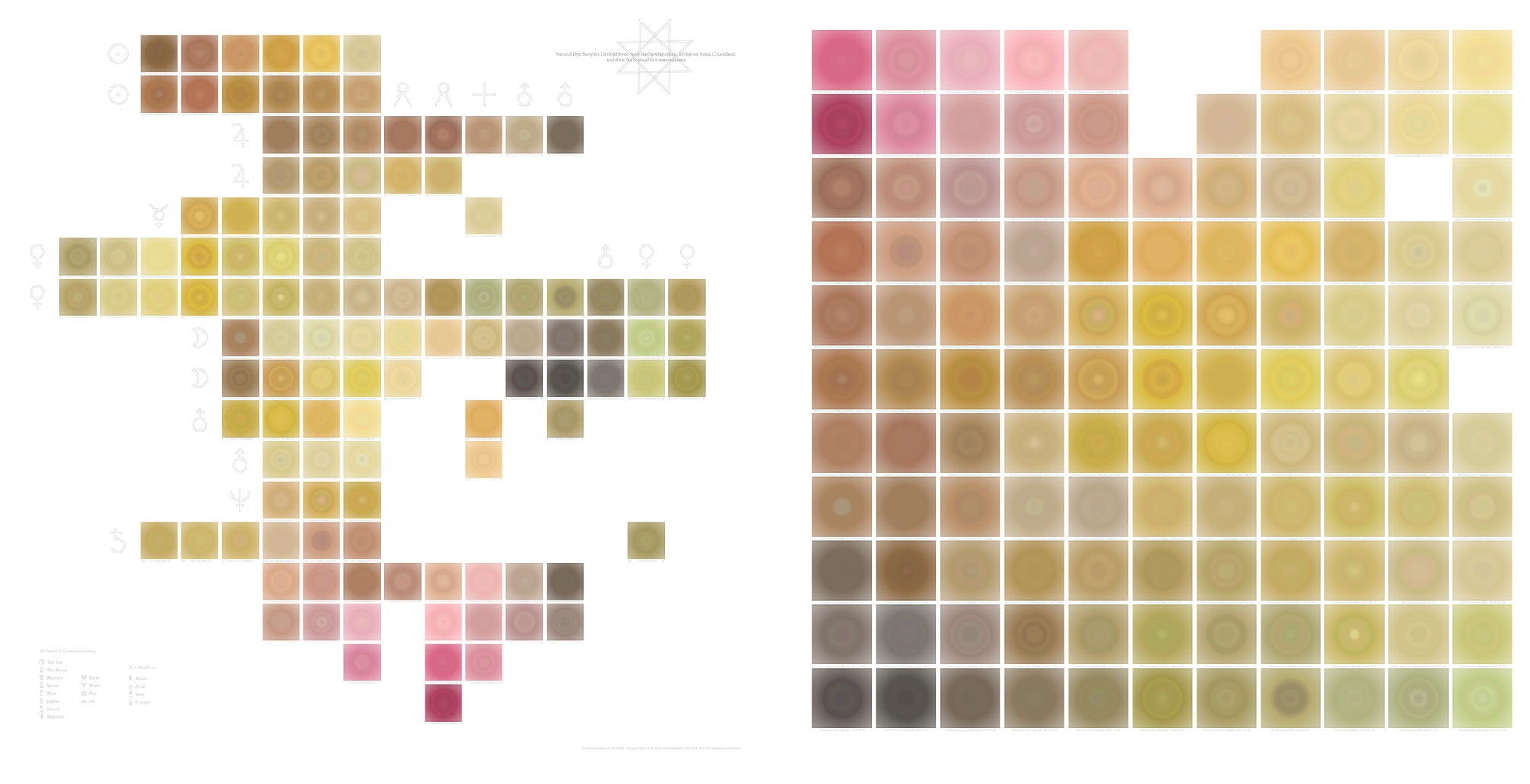

The current exhibition is a process-based collaborative art project combining traditional techniques such as dyeing, spinning and weaving, with data visualization, “performative science” and “relational aesthetics” strategies. Project contributors include Julia Ford, Amanda Hackelton, Jennifer Harman, Soren Johnson, Lizzie Lewis, Lynn Moody, Elizabeth Oriel, Barbara Rosén, and Sydney Wylde. With various methods for visualizing and organizing data, Jevbratt employs a wide range of systematics, from scientific to alchemical, creating a database of natural dye colors.

Mainly plants and one insect (cochineal), the non-native organisms were brought to Santa Cruz Island over an extended period of time, beginning when it was first colonized by Europeans and continuing into the late 20th century. Cochineal, an important source of red dye, was brought to the island in the late 60s to help kill off the cactuses which were considered a hazard to the cows grazing on the island.

“The human immigrants had a relationship to these organisms in their home lands for millennia, many of these plants have been used for food, medicine, magic and dyes,” Jevbrett said. “Just as with humans, some behave better than others when arriving in a new land.”

Referencing the work “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants” by Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Jevbratt noted how examples of non-native species, such as the broadleaf plantain, can be “a generous and healing newcomer, who is truly listening to the new environment.”

Other plants are infamous for wreaking havoc in the ecosystems they “invade.” “On Santa Cruz Island, fennel, a sweet smelling, delicious plant, which is highly medicinal, traditionally used for protection magic and yields a magical yellow color, has taken over large swaths of land to the detriment of the native flora,” she said. “It is now one of the many plants targeted for eradication from the island in a major conservation effort aiming to restore it to a more (real or perceived) natural state.”

The sheep breeds producing the wool and yarns Jevbratt and Svensson are working with have an historical connection to Santa Cruz Island. It’s believed that the Santa Cruz Island sheep breed stems from sheep of several breeds, potentially including Merino, Rambouillet (a French version of Merino) and English Leicester, brought to the island in the mid 19th century for wool and meat production. Over the years, the sheep increased in numbers and became feral, causing massive erosion to the landscape. In the 90s, consistent with restoration efforts on the island, the sheep, then in the tens of thousands, were eradicated. Due to the methods used (very few sheep were brought to the mainland, most were shot on the island) the endemic Santa Cruz Island breed has ironically become one of the five most critically endangered breeds on the Livestock Conservancy’s conservation priority list.

“The wool from these sheep speaks about the landscape where the individual sheep led their lives and the breed emerged. Its staple length and crimp, the soil and vegetable matter trapped in it, reveals something about the sheep, the breed and their environment (craftspeople now speak of the ‘terroir’ of wool),” said Jevbratt, originally from Sweden, who joined UCSB’s Art Department and Media Arts and Technology program in 2002. Before turning her focus to textiles, for more than a decade she explored the expressions and exchanges created by the protocols and languages of the internet, often manifesting as visualization software. Her work has been exhibited extensively in venues such as The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Banff Centre for the Arts in Canada, The New Museum in New York, The Swedish National Public Art Council in Stockholm, Sweden, and the Biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

“Interlopings” relies on visual, tactile and olfactory modalities of generating meaning, she added. “As such the most important questions will be asked, and maybe answered, in the direct experiences of hands, noses and eyes and in the relationships created between people and between people, processes and materials.”

Debra Herrick

Associate Editorial Director

(805) 893-2191

debraherrick@ucsb.edu