Colonizers were known to carry books in their luggage. In the early 1500s, books began to arrive in America by the thousands, destined for the capital of New Spain, Mexico City, and other urban hubs in Spain’s territories. A century later, Catholic monarchs in Spain learned of crypto-Jewish books across the Atlantic Ocean. They ordered all bookstores to submit detailed inventories to the Mexican Inquisition — an extension of the Spanish Inquisition — freezing in time a record of the reading materials that circulated among New Spain’s intellectual class.

For Spanish Professor Antonio Cortijo Ocaña, who researches early modern Spanish literature at UC Santa Barbara and is the author of over 50 books on the topic, these lists are a window into what people were thinking about during an important ideological shift. Descendants of Spanish-born colonizers transitioned from identifying with the Spanish Crown in Europe to thinking about a new American or Mexican identity.

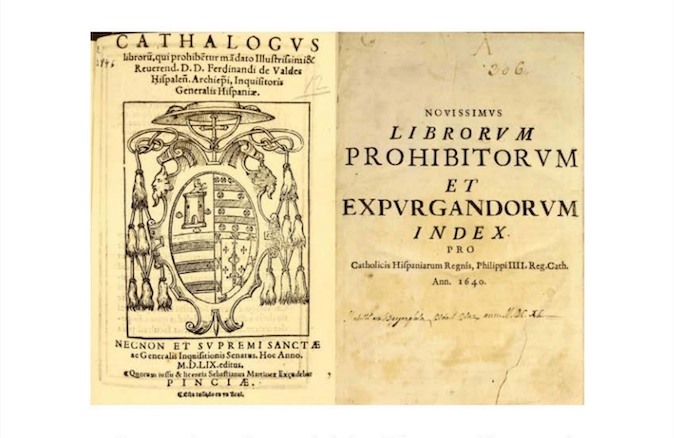

“They used the inventories to make sure none of the books were included in Spain’s ‘Index of Forbidden Books,’” said Cortijo Ocaña, who recently published a study of eight unknown and previously unedited inventories, shedding further light on the cultural and ideological foundations of New Spain.

“But the people creating these lists were also creating the consciousness of what is a ‘new Mexican’ or ‘new Spaniard’ or ‘Mexican’ and such. There’s a moment when people who are living in New Spain start to feel like they belong to New Spain and not to Spain,” he said.

The Spanish administration relied on books to prepare bureaucrats, lawyers and clergy — the learned elites of the new territories. Cortijo Ocaña noted, “Spanish-Mexican elites were composed of doctors, lawyers and merchants or entrepreneurs who learned their professions largely through books and university studies in cities in Spain, Mexico, Perú, Guatemala or the Dominican Republic.” By 1539, the first printing press was established in Mexico City and still, thousands of books continued to be imported from printing presses in Spain and Spanish Europe (Italy and the Low Countries).

In his book “Memorias de libros. Censura inquisitorial y comercio de libros en Nueva España. Siglo XVII” (Tirant lo Blanch) — on book inventories, inquisitional censorship and the book trade in 17th century New Spain — Cortijo Ocaña offers close readings of lists submitted between 1680 and 1684 by bookshop owners in Mexico City and Puebla. He analyzes the contents of the books, the networks of distribution between Europe and America, and the shifting concepts of national and cultural identity revealed by the books in circulation.

“In order to develop their ideas and to conceptualize society, they were reading and basing their thinking on what they were reading,” said Cortijo Ocaña.

Debra Herrick

Associate Editorial Director

(805) 893-2191

debraherrick@ucsb.edu