An Informed Citizenry

A little over two years ago, communication professor Joe Walther taught a graduate seminar at UC Santa Barbara that focused on fake news — what it is, where it comes from, how to identify it and how the public can protect itself from being duped. Out of the course came a website, “A Citizen’s Guide to Fake News,” produced by doctoral students as a resource accessible to the general public, designed to be comprehensive as well as politically neutral.

So far 2020 has been a banner year for the project: The guide has been viewed more than 121,000 times by readers around the world. And in the past month — from September 29 to October 29 — viewership increased 133% over the previous month, with more than 22,000 views.

“We’re surprised and we’re not surprised,” said Walther, director of the campus’s Center for Information Technology and Society, an interdisciplinary collective of researchers and students who share interests in the design, implementation and effects of technology on all aspects of our lives. “We aimed to present enduring principles based on sound research that would have some longevity. At the same time, it seemed as though government investigations and promises for accountability from the tech industry might diminish the level of fake news in circulation now. We didn’t foresee that foreign interference would largely be replaced by domestically produced misinformation as much as it has been, keeping our material as relevant as ever.”

Peak readership occurred on Oct. 29, when the site was viewed 1,339 times in one day. On average, readers spend more than five minutes on the site. Among the more popular pages: “A Brief History of Fake News,” accounting for 22% of total page views. Next was “How Fake News is Spread — Bots, People Like You, Trolls and Microtargeting” followed by “The Danger of Fake News to Our Election.”

“Although a lot of fake news has been domestic, the mainstream media and national intelligence agencies have kept people aware that there’s still a lot of fake news confronting Americans from foreign adversaries, too,” Walther said.

And Americans aren’t the only people consulting the guide. According to Walther, 48% of readers seem to be in the United States. Others come from the Philippines, Canada, India, the United Kingdom, Germany and China, among others.

“That tells us that fake news is a global problem, and that other countries have their eyes on the American election,” Walther said.

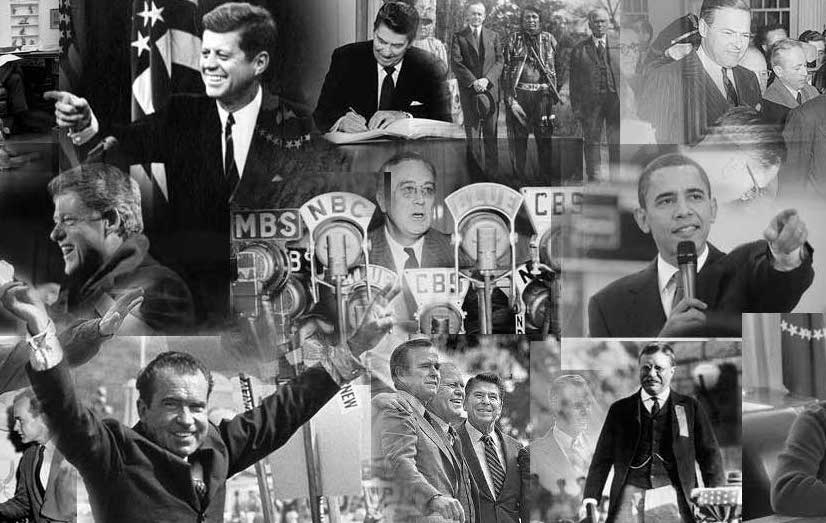

Elsewhere on campus, the American Presidency Project (APP), a non-partisan online source for presidential public documents, also has seen a remarkable increase in traffic during this election cycle. The searchable database includes 137,721 presidential and non-presidential records.

According to co-director John Woolley, professor emeritus of political science, viewership in September and October is nearly double that of the two previous months. “There also has been a shift in the composition of visited pages,” Woolley said. “The biggest proportionate increase in page views was for our generic guidebook for APP elections resources, with 14-fold increase in page views.”

The greatest numerical increase in page views (from 10,000 to nearly 64,000 views) — and also the second-largest proportionate increase — was for the APP page with data on “Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections.” In addition, in the two months leading up to the election, the Executive Orders page had a total of almost 50,000 views. “Visits to both pages were undoubtedly stimulated by mentions in national media,” Woolley noted.

“Over time we’ve broadened our collection in many ways, adding official documents that were not part of the ‘official’ compilations — many executive orders and proclamations — adding new categories of documents such campaign sources and Twitter, and adding a great deal of detail about individual presidents,” said Woolley.

“We’re gathering many examples of 19th-century Presidential popular speech that were excluded from the official compilations,” he continued. “We’re in the process of creating ‘timelines’ for each president to highlight some of the most important issues they’ve dealt with, and to assist users in navigating our site.”

Woolley added that the timeline project will help create more “modern” and, in many ways, a more “ambivalent” perception of presidents, consistent with the critical tone of much of our current politics. “So, for example, we can include in the timeline important dates and events in movements for women’s rights and racial equality — implicitly pointing to the ways presidents did and did not connect with those movements,” he said.