The term “wine grower” is so common that we never think about how little sense it makes. Vintners aren’t “growing” wine. They are growing grapes, then producing wine from those grapes. So why do we use that odd phrasing?

It turns out there’s a story behind it, according to cultural historian Lisa Jacobson, an associate professor at UC Santa Barbara.

“The term was a clever invention by a lawyer for the Wine Institute who wanted to take advantage of a marketing program run by the California State Department of Agriculture in the 1930s,” she said. “To take part, you had to convince them that you produced an agricultural product. This was the linguistic invention they used to do that.”

In addition, the term’s imagery was useful, in that it “evoked the romantic idea of the gentleman farmer,” Jacobson added. “One way to overcome the stigma linked to alcohol was to associate yourself with agrarian virtue.”

As that bit of linguistic history suggests, the story of how alcoholic beverages morphed from disreputable habit to ubiquitous facet of American life is a complicated and fascinating one. Contrary to many people’s assumptions, the lifting of Prohibition in 1933 did not, by itself, usher in a golden age of drinking in America. The habit had to be cultivated.

How and why that happened is the topic of Jacobson’s book “Intoxicating Pleasures: The Reinvention of Wine, Beer, and Whiskey after Prohibition” (UC Press, 2024), which traces the changing image of imbibing from the 1930s to the end of World War II. She argues that, when prohibition was lifted, a lot of the stigma surrounding drinking remained. It took a concerted campaign and many years to make alcohol consumption an accepted part of middle-class American life.

“The beverage industry knew it had its work cut out for it,” she said. “They launched massive public-relations and advertising campaigns that reinvent drinking as an emblem of the good life — of middle-class respectability.

“Thanks in large part to those efforts, wine, beer and whisky have very distinctive cultural identities. I wanted to understand how that came into being — where their paths converged and diverged,” she added.

This history remains resonant for several reasons. Contemporary challenges including new tariffs on both imports and exports, as well as growing scientific consensus that even moderate drinking can be bad for you, have the potential to upend ingrained drinking habits. Understanding the forces that shaped those patterns in the first place is of obvious value.

At the same time, a new group of formerly illegal behaviors are rapidly gaining respectability, including marijuana smoking and sports gambling. The path to alcohol acceptance that Jacobson lays out could be applied to those industries to examine the extent to which their growing social acceptance is orchestrated as opposed to organic.

“I’m always interested in trying to understand how products and practices that were once viewed as disreputable eventually get mainstreamed and accepted,” she said.

In the case of alcohol, women were crucial to the normalization campaign. After all, as Jacobson noted, “they were the foot soldiers of the prohibition movement. They were often the ones who decided how much and what type of alcohol entered the home. So there was an effort to incorporate alcohol into domestic settings, and present drinking as an element of good hospitality.

“The idea was women were the ‘civilizing’ force, and you could encourage drinking in moderation as long as women are present. This idea was promoted in these campaigns, to counteract the image of the very masculine saloon.

“In addition, home economists join in promoting wine and beer as an adjunct to entertaining. Lots of people wrote guidebooks to drinking etiquette — what to serve guests, how to have good taste, how to drink in socially responsible ways.”

Alcohol, in this telling, was not about getting drunk.

“Wine was increasingly marketed as the drink active, busy people choose,” Jacobson noted. “That was a way of saying it was consumed by people who are employed — people who don’t want a hangover, so they drink in moderation. These are people who enjoy good conversation, who enjoy the extra conviviality alcohol might add to socializing.”

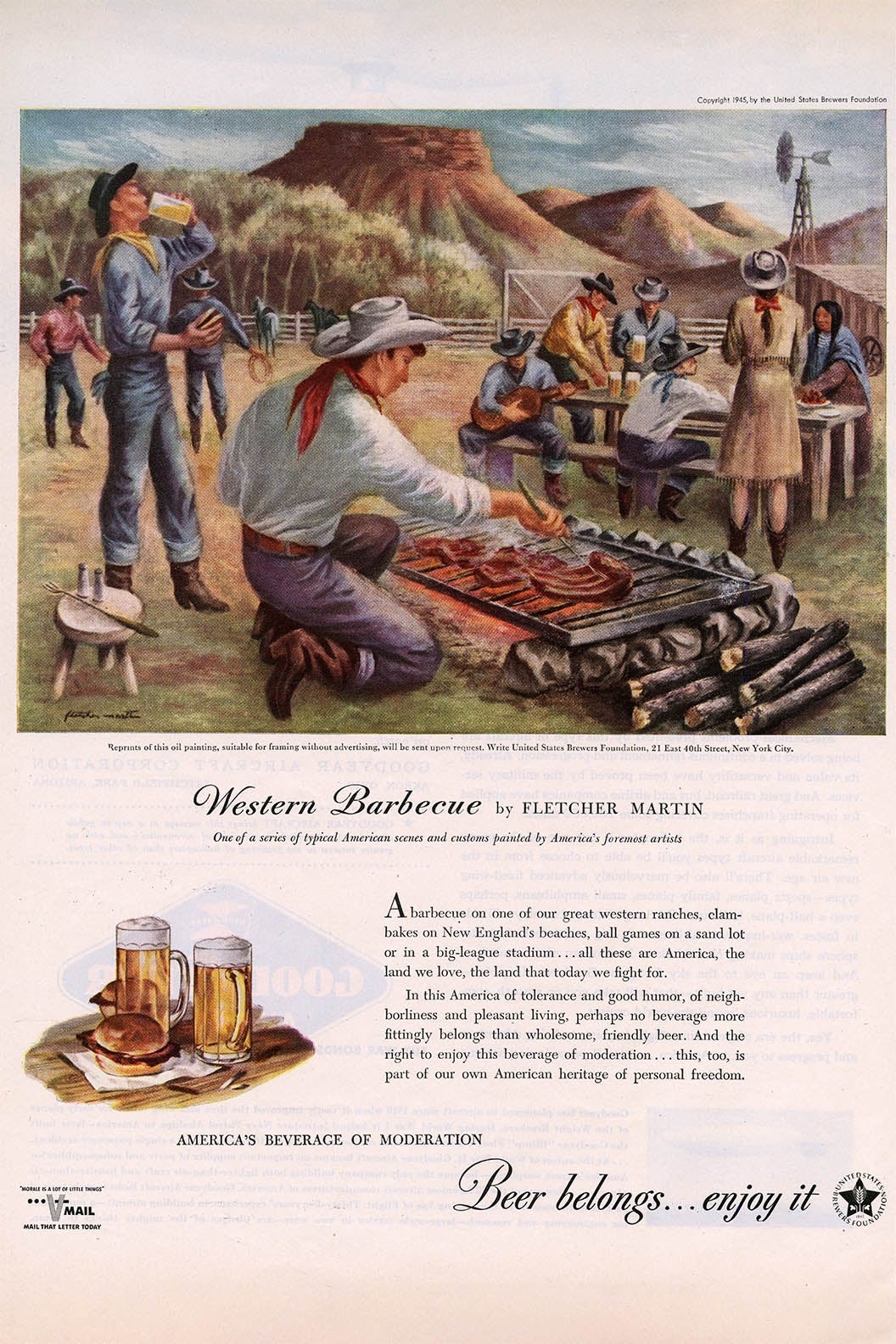

A similar approach was taken by brewers. “From World War II into the 1950s, beer was promoted as genteel — respectable enough that women could serve it to guests,” she said. “They were trying to distance beer from its roots in the rowdy, masculine careers by placing it in domestic settings like family gatherings. They also connected beer to Americana — the drink you serve at barbecues and roof-raisings.”

That campaign was not a complete success. By the mid-1950s, the beer industry realized it had “overstepped the mark and decided to embrace its working-class, masculine identity,” she said.

For her part, Jacobson is a wine drinker and incorporates alcohol into homemade desserts. “My father was a wine connoisseur,” she said. “He was influenced by California wine propaganda. He went to medical school at UCSF, where there was a standard wine course for medical students. It was part of the curriculum!”

In one of her first jobs out of college, she worked for the regional oral history office at UC Berkeley. “They have a long-running oral history series on California winemakers. I participated in some of those interviews and attended a few industry conferences in the late 1980s,” she recalled.

“This was a period where you saw much tougher alcohol regulations. I saw the wine industry attempting to reassert itself as the beverage of moderate drinkers” — just as it had a half-century earlier.

At UCSB, Jacobson teaches several courses on cultural history, including a popular one on the history of food. She is also working on a second volume of her history of social drinking in America, focusing on the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s.

She will leave the still-unfolding history of cannabis consumption to future historians.

“I suspect cannabis may be heading for a few bumps in the road,” she said. “It’s never a straight line from demon to darling.”