In the fall of 1977, Nori Muster was starting her senior year at UC Santa Barbara. A transfer student from Humboldt State, she was working towards a degree in sociology. Like so many young adults, she was also asking fundamental questions about why we are here, and how we should live.

“At that time, every single cult was represented in Santa Barbara,” she recalled. “I was looking for answers, so I checked some of them out.”

Over the course of the school year, she was cultivated by the Hare Krishnas, a phenomenally popular movement that promised a path to inner peace. The day after she graduated, Muster packed up her car and drove to Los Angeles. She moved into a temple and began a decade of work in the public relations department of the International Society of Krishna Consciousness.

She regrets her decision to this day.

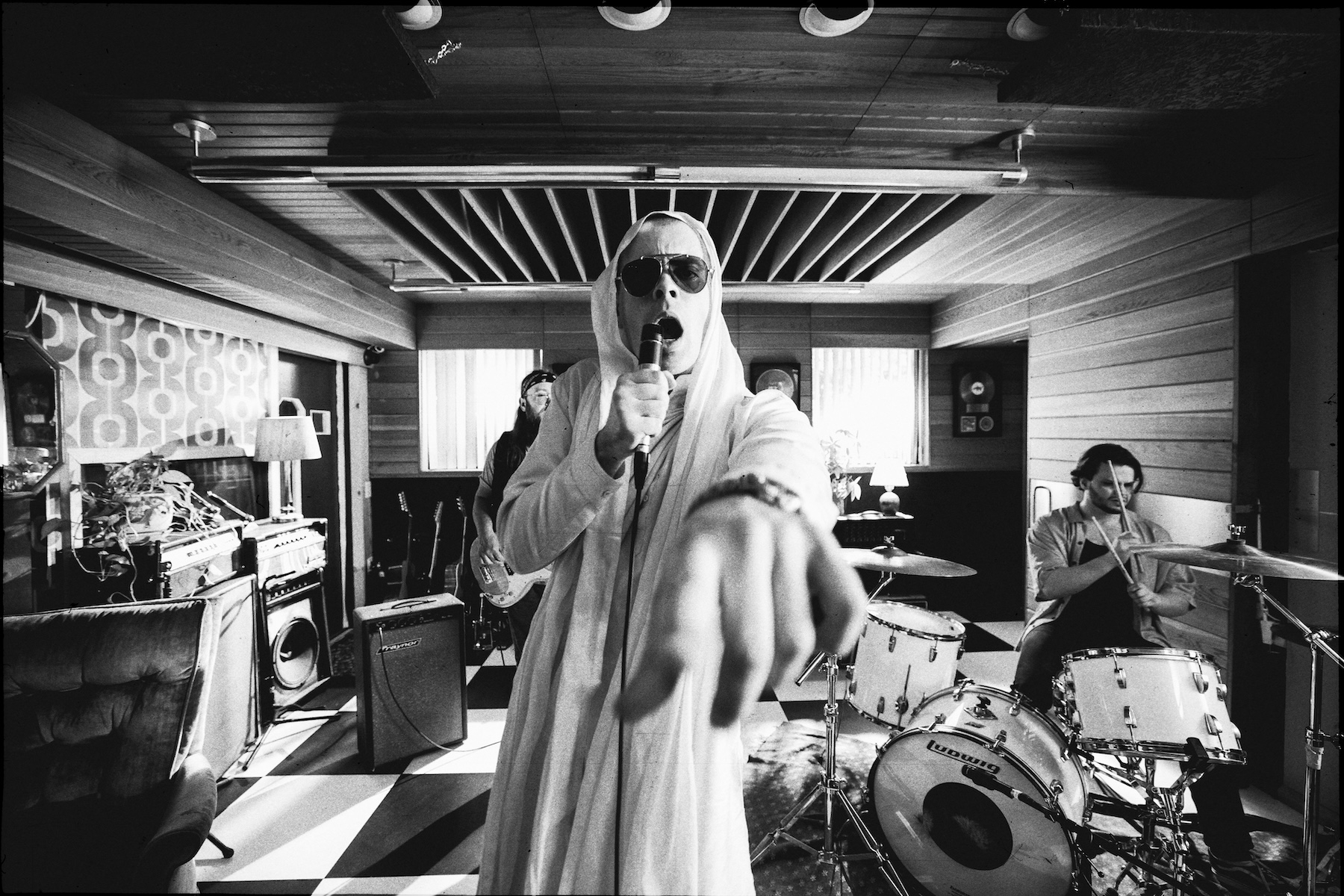

Muster is a central narrator of “Monkey on a Stick,” Jason Lapeyre’s documentary about the Hare Krishnas, which will be screened at 7 p.m. Thursday, April 10, in the Pollock Theater on the UC Santa Barbara campus. Afterwards, she and Lapeyre will answer questions about the film, some of which was filmed at the UCSB Library, where Muster’s remarkable collection of documents from her time with the organization is housed.

“The film is not a critique of Krishna consciousness as a religious movement,” said Lapeyre. “Eastern philosophy has much to teach the world. The film is about a corrupt organization that spun out of control.”

Founded in 1965, the Hare Krishna movement is perhaps most remembered for its devotees’ habit of swarming airport lounges asking for money. Derived from ancient Hindu scripture, the practice emphasized chanting the name of the god Krishna, along with yoga, vegetarianism and a prohibition against alcohol, drugs and recreational sex.

It was, according to founder A.C. Bhaktivedanta, a method to escape the cycle of reincarnation. But in reality, it created a sinister cycle of cultishness and criminality, in which drug trafficking, child abuse and even murder were covered up to protect the organization.

“I think (the founder) was naïve,” Muster mused. “He accepted money from drug smugglers, believing their service to Krishna would purify them.”

After his death, which occurred while Muster was first exploring the movement, power was passed to a group of 11 “gurus” — young, inexperienced men who were each, in essence, given their own fiefdom to rule over. As John Hubner and Lindsay Gruson document in the 1988 book that served as the foundation of the film, the results were often ugly.

“John says something profound in the introduction to the book: Power corrupts, but no power corrupts as absolutely as fanatical religious power,” Lapeyre recalled. “In this case, that led to child sexual abuse and murder.”

The Vancouver-based director read the book in 2000, after it was given to him by a friend. “The contrast between the ideals espoused by Krishna consciousness — peace and anti-materialism — and the violence, corruption and abuse the book exposes — those two things were so at odds with each other that I immediately thought, ‘This needs to be a film,’” he said.

He worked for years to try to turn the story into a feature film, until “it eventually became clear that the shortest path to doing anything with the book was to make a documentary first, and use that as a springboard to make a drama. That’s still the plan.”

Perhaps reflecting that mindset, the movie includes several recreations of dramatic moments as performed by actors — including a gruesome murder and decapitation.

“I want people to be outraged by this story,” he said. “A good way to make people feel that is to dramatize these true events. These are things that actually happened. They are backed up by our research and interviews.”

How did the organization lose its way so badly? “I think it was a combination of a few fatal decisions and mistakes that were made,” Lapeyre said. “One was giving human beings unlimited, unquestioned power. That never works out. Shakespeare knew this!

“Another was the core belief that men are superior to women. I think that was a cancerous belief that was doomed to metastasize into something awful.”

That gender imbalance was one reason he was particularly interested in working with Muster, one of the few females with knowledge of the organization’s inner workings. “As a PR person for the group, she was so perfectly located to both witness the victimization that was happening and the cover-up,” he noted. “Nori organically emerged as the heart of the documentary.”

She ultimately became an associate producer of the film. “I gave her a voice in the editing,” Lapeyre said. “She was not just a historical fact-checker: I wanted her to approve of the way the story was told. It’s her life!”

Now living in Arizona, Muster — who wrote her own memoir, “Betrayal of the Spirit,” in 1996 — is largely satisfied with the film, a version of which is streaming on AMC Plus and Sundance Now. (The Pollock screening, which features Lapeyre’s preferred director’s cut, is free. Reservations are recommended.)

But for her, its subject remains difficult to face.

“I still feel shame for what I did there,” she said. “If you do something that hurts other people, you should feel shame.”

That said, the screening at the Pollock Theater should serve as something of a homecoming. Not only did Muster first connect with the Hare Krishnas in Santa Barbara, but what Lapeyre calls “crucial filming” was done at the UCSB Library.

“I always knew I wanted to film her at UCSB with her archives, showing us what she had kept,” he said. “While we were filming there, she said, ‘This is the history the organization is trying to erase. But if you forget the past, you are doomed to repeat it. And that’s called karma.’

“Sadly, that idea is so relevant right now,” he added. “People are ignoring history or pretending it didn’t exist, as they try to impose their power on other people. There’s a real timeliness to that message.

“So many times, during a Q&A after a screening of the film, somebody will ask, ‘Did you make this about right now?’ My answer is ‘yes and no.’ This story reflects human nature.”