Fish Feed Foresight

As the world increasingly turns to aqua farming to feed its growing population, there’s no better time than now to design an aquaculture system that is sustainable and efficient.

Researchers at UC Santa Barbara, the University of Tasmania and the International Atomic Agency examined the current practice of catching wild fish for forage (to feed farmed fish) and concluded that using novel, non-fishmeal feeds could help boost production while treading lightly on marine ecosystems and reserving more of these small, nutritious fish for human consumption.

“The annual catch of wild fish has been static for almost 40 years, but over the same period the production from aquaculture has grown enormously,” said Richard Cottrell, lead author of a paper that appears in the journal Nature Food.

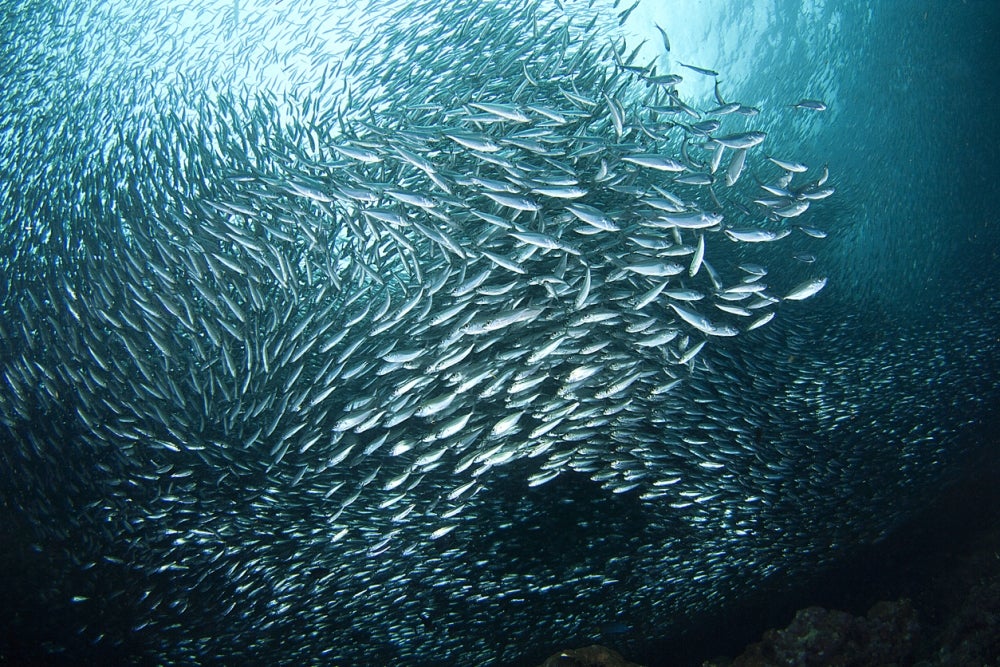

Approximately 16 million of the 29 million tonnes of forage fish — such as herrings, sardines and anchovies — caught globally each year are currently used for aquaculture feed. To meet the growing demand for fish in a sustainable manner, other types of fish feed must be used, the researchers said.

“We looked at a range of scenarios to predict future aquaculture production and, depending on consumer preferences, we found growth between 37-98% is likely,” said Cottrell, a postdoctoral scholar at UCSB’s National Center for Ecological Analysis & Synthesis (NCEAS), who conducted this work at the University of Tasmania.

Fortunately, nutritional sources exist that could ease the growing demand for forage fish. Based on microalgae, insect protein and oils, these novel feeds could, in many cases, at least partially substitute fishmeal and oil in the feeds of many species without negative impacts on feed efficiency or omega-3 profiles.

“Previous work has identified that species such as carps and tilapias respond well, although others such as salmon are still more dependent on fish-based feeds to maintain growth and support metabolism,” said Cottrell, who with his colleagues analyzed results from 264 scientific studies of farmed fish feeding experiments. As the nutrition and the manufacturing technologies improve for these novel feeds, they could allow for substantial reductions in the demand for wild-caught fishmeal in the future, he added.

“Even limited adoption of novel fish feeds could help to ensure that this growth (in aquaculture production) is achieved sustainably,” Cottrell said, “which will be increasingly important for food security as the global population continues to rise.”

As we lean more on ocean-based food, the practices in place for producing it must come under scrutiny, and be improved where possible, according to UCSB marine ecologist and co-author Ben Halpern, director of NCEAS.

“Sorting out these questions about feed limitations and opportunities is nothing short of essential for the sector, and ultimately the planet,” he said. “Without sustainable feed alternatives, we will not be able to sustainably feed humanity in the future.”

This study is one of several examinations of the potential for novel feed ingredients to replace wild caught forage fish in aquaculture.

“Our future research will continue to look at the wider consequences and trade-offs of shifting toward novel feed ingredients, including assessing the impacts on both marine and terrestrial environments, as well as balancing these with social and economic outcomes,” said University of Tasmania associate professor and study co-author Julia Blanchard.

Research in this study was conducted also by Halley E. Froehlich at UCSB and Marc Metian at the International Atomic Agency in Monaco.