A Woman's Place

A film about a little-known female architect has made a big splash at this year’s Santa Barbara International Film Festival. “Lutah,” directed by Kum-Kum Bhavnani, sociology professor at UC Santa Barbara, is scheduled for another screening at the Lobero Theatre this weekend.

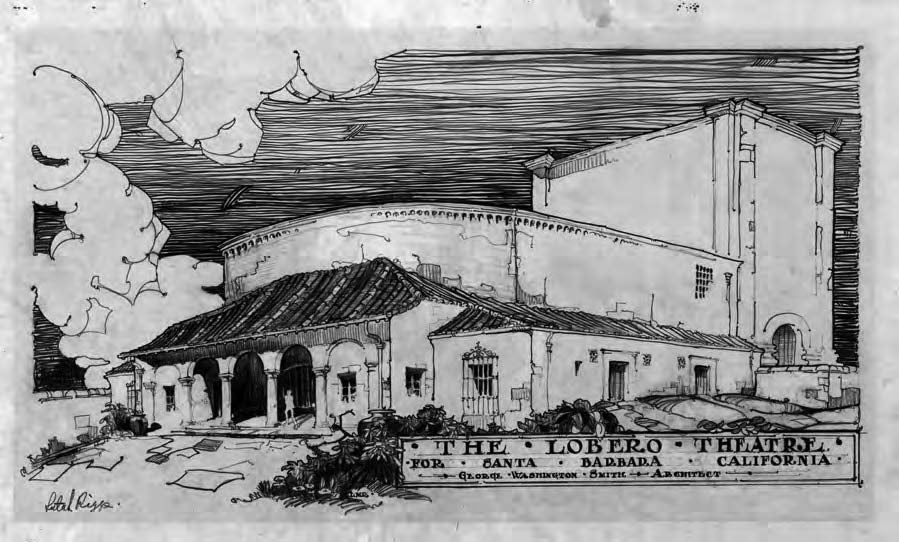

If Lutah Maria Riggs, who was instrumental in Santa Barbara’s Spanish Revival aesthetic — red tile roofs, arched doorways and colonnades, just to name a few elements — saw the lines that formed around the very theater she designed almost a century ago to see the film about her life, she might have been pleased at the attention her work was getting…but perhaps not as concerned about the notice directed at her. “I dedicated myself to architecture,” she once said. “…it comes first, I come last.”

Nevertheless, film buffs, art historians, architecture enthusiasts and those who just wanted to hear a good story have made it clear that the woman behind the Lobero, who worked under the renowned George Washington Smith to make Santa Barbara look the way it does, is worth the attention. A woman who accomplished more than anyone of her gender was expected to during a time and in a profession dominated by men, Riggs was also a pioneer for women, and a worthy subject for Bhavnani, who specializes in social justice documentaries.

“I felt that Lutah…was someone who, through her fiercely independent approach to her work, and life in general, had been a pioneer both architecturally and for women’s rights,” said Bhavnani. Though not initially interested in the project, a conversation with the film’s producers, Leslie Bhutani and Gretchen Lieff, as well as Riggs’ archivist Melinda Gandara, convinced her that this was a story that needed to be told, particularly because Riggs was an independent woman who contributed so much to her community.

For Riggs, who hailed originally from Ohio, early life was punctuated by misfortune. Her father abandoned the family when she was two years old, forcing her mother to rely on in-laws to keep Lutah and her sisters above water. After her father’s death, her mother married twice more, and it was the second stepfather who was instrumental in getting the future architect from away from the Midwest and to Santa Barbara in 1914.

The West Coast proved to be the best place for the young woman, who continued her studies and found her growing fascination with architecture at the local junior college and eventually headed up north to UC Berkeley, where she got her degree.

Perhaps it was the continuous struggle her mother went through to support the family, or the constant disappointment in the father figures in her life, but by the time Riggs was ready to embark on her own life, her decision to remain single and concentrate on her career was made — not an easy choice during a time when a woman’s greatest achievement was a marriage and family.

“I really have enjoyed that she was a woman who was fiercely independent — she lived her life in the way she wanted to and did it such that her clients and contractors accepted it. In other words, as someone says in the film, she was a ‘pioneer’ and a ‘trailblazer’ while also being a brilliant architect,” said Bhavnani

And yet, she was a homemaker, in that she was concerned with more than just the structure of the buildings she designed, but also with how they would be used.

“She did tend to ask clients what light they liked, where they ate breakfast, did they want to have relationships to the sun,” said Bhavnani. “That is, she was interested in the lived experience of the people — rich or of more modest means — before she designed residences.” Riggs also became more spiritual (“not religious, but spiritual,” Bhavnani emphasized), allowing her to design buildings with both beauty and function in mind. The harmony between building and landscape that persists in Santa Barbara today can be credited in large part to Lutah Maria Riggs.

“Lutah,” screens at the Lobero Theater this Sunday, February 9 at 7 p.m.