On a sunny, windy morning 10 UC Santa Barbara undergraduate students peer over the edge of the Long Valley Caldera, the remnant of a supervolcano that erupted 760,000 years ago. From their vantage point, on the side of Mammoth Mountain in California’s Eastern Sierra, they take selfies with the 20-mile-long, 11-mile-wide crater — ephemeral humans against a landscape forged by magma and sculpted by glaciers.

Only a few steps away is one of the world’s premiere snow labs, the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, also known as CUES. From the partially buried bunker and surrounded by supplies and equipment, climate scientist Ned Bair talks about a life spent studying snow: the cold, the rigor, the danger.

“It’s hard,” he said. “It’s hard on your body.” Indeed, even at this 9,600-foot altitude the air is thinner, forcing the unacclimated to breathe faster and deeper, and to be more deliberate about their movements. At an elevation this much closer to the sky, the sun also shines brighter, with less of the atmospheric cover that shields the lower elevations from the brunt of its rays.

None of these challenges faze UCSB environmental studies major Liv Valinsky, because she has just gotten a precious glimpse of her possible future, and it is bright. A lifelong outdoors person with a newfound interest in atmospheric science, Valinsky’s brief contact with Bair was enough to stoke her passion for the subject and sharpen her focus on a life in environmental science.

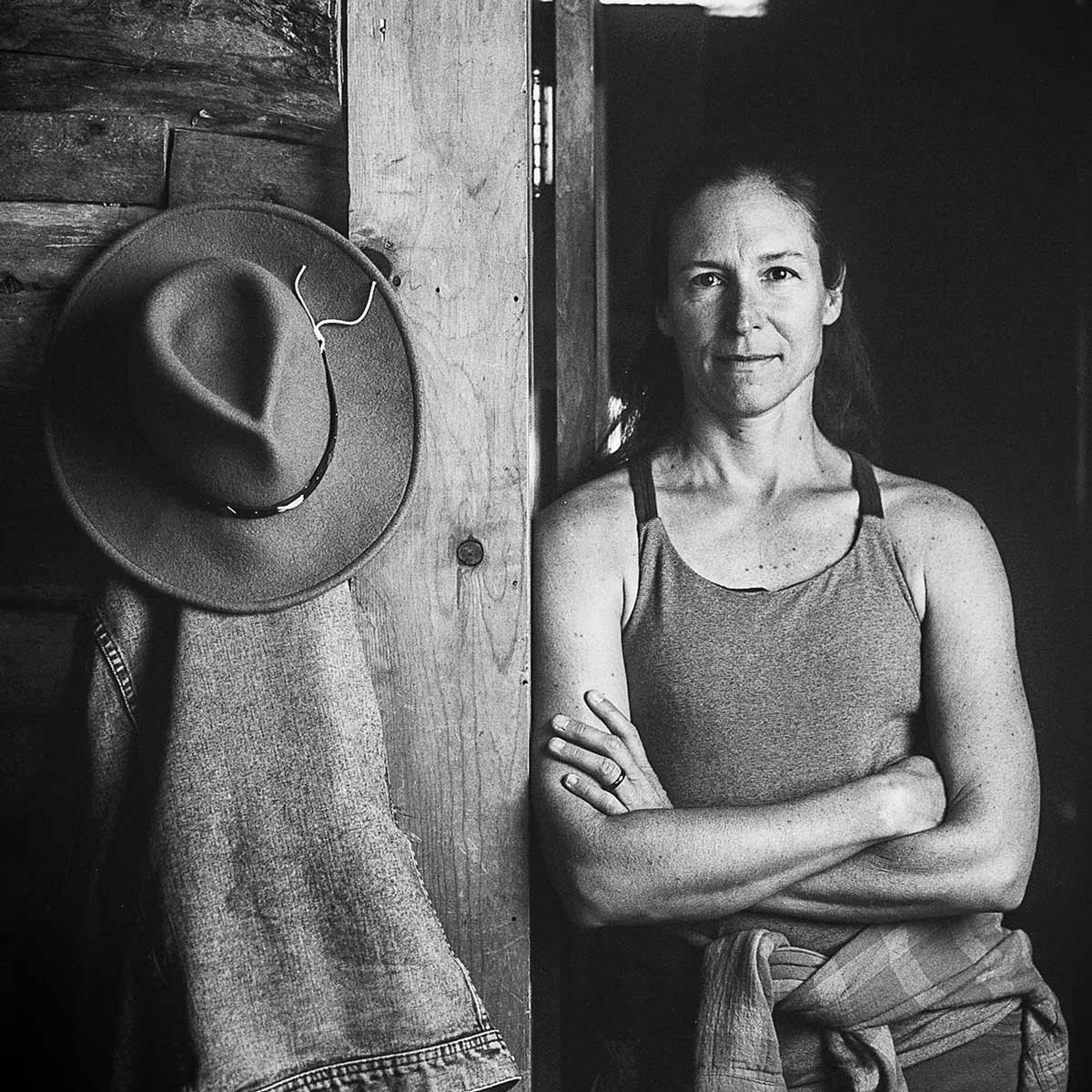

FUERTE participant Liv Valinsky at Valentine Camp

"It was really cool to talk to him,” she said. “Just to see someone that’s in a career that’s so similar to what I want to pursue and the instruments he’s using and where he ended up in life, it’s so exciting.”

Valinsky’s experience is just one of many doors that UCSB opens for its undergrads into the world of conservation and environmental science. As a participant in the FUERTE (Field-based Undergraduate Engagement through Research, Teaching and Education) program, she and the rest of her cohort are getting a firsthand taste of what it’s like to be a field scientist while developing the fundamental skills necessary to get their future careers off to a good start. Funded by a National Science Foundation program to enhance STEM education for underserved communities, the FUERTE students are taught and taken into the field by world-class UCSB scientists and mentored by a cadre of graduate students in the Department of Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology (EEMB). They grow their skillsets over three summers, building an impressive resume of projects, fieldwork and internships before they graduate.

For each participant, the adventure begins with a two-week intensive summer course that exposes them to a variety of ecosystems located in the rain shadow of the “granite curtain” that is the East Sierra Nevada mountain range. In this region of California, UCSB administers, as part of its system of natural reserves, the Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserves (VESR), the collective name for two separate protected spaces: Valentine Camp in the town of Mammoth Lakes and SNARL, the Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Laboratory, a former US Fish and Wildlife research station just a short drive away.

“The Eastern Sierra provides an amazing opportunity for training for environmental sciences with a wide array of ecosystems and habitats, ranging from the High Sierra alpine ecosystems to Great Basin sagebrush and including montane forests, high desert habitats and unique aquatic ecosystems from alpine lakes to saline lakes, and rivers, streams and high desert pools,” said VESR director Carol Blanchette. The reserves provide easy access to most of these habitats, she continued, and both of them offer opportunities to study stream ecology in a place where water is most precious.

Carol Blanchette, director of the Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserves.

Alpine

At the highest elevations of the Sierra Nevada, conditions are harsh, yet life will take hold if it can find even a little bit of shelter and moisture. Despite the inhospitable environment, the alpine biome hosts hundreds of compact plant species and hardy animals, including bighorn sheep, and mountain lions.

Montane

The montane ecosystems of the Eastern Sierra are among the most biodiverse of the region, hosting a variety of plants and animals in its relatively mild climate. Conifers, aspens and oaks are the major trees of the area, while the grasslands provide forage and breeding grounds for black bears, mule deer and several species of raptor.

Sagebrush

Low-growing sagebrush scrub — a community of plants adapted to the arid environment of the lowest elevations of the Eastern Sierra — populate the desert floor in a vast sea of gray-green plants. This ‘sagebrush sea’ hosts hundreds of species, including the iconic sage grouse, as well as rattlesnakes and small rodents.

Because of their locations and facilities, Valentine and SNARL are hubs for environmental scientists who study the area, making them ideal places for students contemplating a life in the environmental sciences, Blanchette added. Here, the students have access to decades of field science in this remote part of California, and also to its relatively untouched beauty. It’s a beauty that once led noted 19th century environmentalist John Muir to call the Eastern Sierra “a country of wonderful contrasts,” while early 20th century writer Mary Austin praised the area’s “luminous radiance” and its “lotus charm.” It’s a beauty that landscape photographer Ansel Adams never tired of as he aimed his camera again and again at the Sierra Nevada and where it touches the sky.