New UCSB research shows p-computers can solve spin-glass problems faster than quantum systems

It remains an open question when a commercial quantum computer will emerge that can outperform classical (non-quantum) machines in speed and energy efficiency while solving real-world combinatorial optimization problems. In the meantime, the probabilistic computer — or p-computer — built from probabilistic bits, or p-bits, has continued to prove its value as an intermediate and practical approach. It’s a specialty of UC Santa Barbara electrical and computer engineering (ECE) associate professor Kerem Çamsarı, whose group has helped establish p-computing as a promising alternative for tackling hard optimization tasks.

Two recent papers underscore that potential. In one study, Çamsarı and collaborators at Northwestern University examined how synchronous probabilistic computers — in which p-bits update largely in parallel — compared to the asynchronous architectures his group first developed, where each p-bit updates independently and stochastically.

“In this work, the team achieved two exciting milestones,” Çamsarı said. “First, we showed that using voltage to control magnetism can produce highly efficient probabilistic bits. Second, we demonstrated that a carefully synchronized architecture — where all bits update together, like dancers moving in lockstep — can match the performance of conventional designs, in which each bit updates independently and unpredictably.”

In the most recent paper, published in the journal Nature Communications, Shuvro Chowdhury, a postdoctoral researcher in the Çamsari lab, and 14 co-authors, including Çamsari and fellow ECE professor and department chair, Luke Theogarajan, demonstrate that their p-computer design can outperform a leading quantum annealer on the same “spin-glass” benchmarks commonly used to evaluate hard optimization problems.

Titled “Pushing the Boundary of Quantum Advantage in Hard Combinatorial Optimization with Probabilistic Computers,” the paper responds in part to a claim that a privately built quantum computer had solved spin-glass problems faster and more effectively than any competing technology. Chowdhury and the team, comprising individual experts assembled to address the numerous specific challenges facing them, showed that with enough p-bits, a probabilistic computer might have the edge in speed and efficiency.

“This is an impressive piece of work from the Çamsari Lab,” Theogarajan said. “It’s a truly remarkable result that illustrates the power of p-bits and their future in computing.”

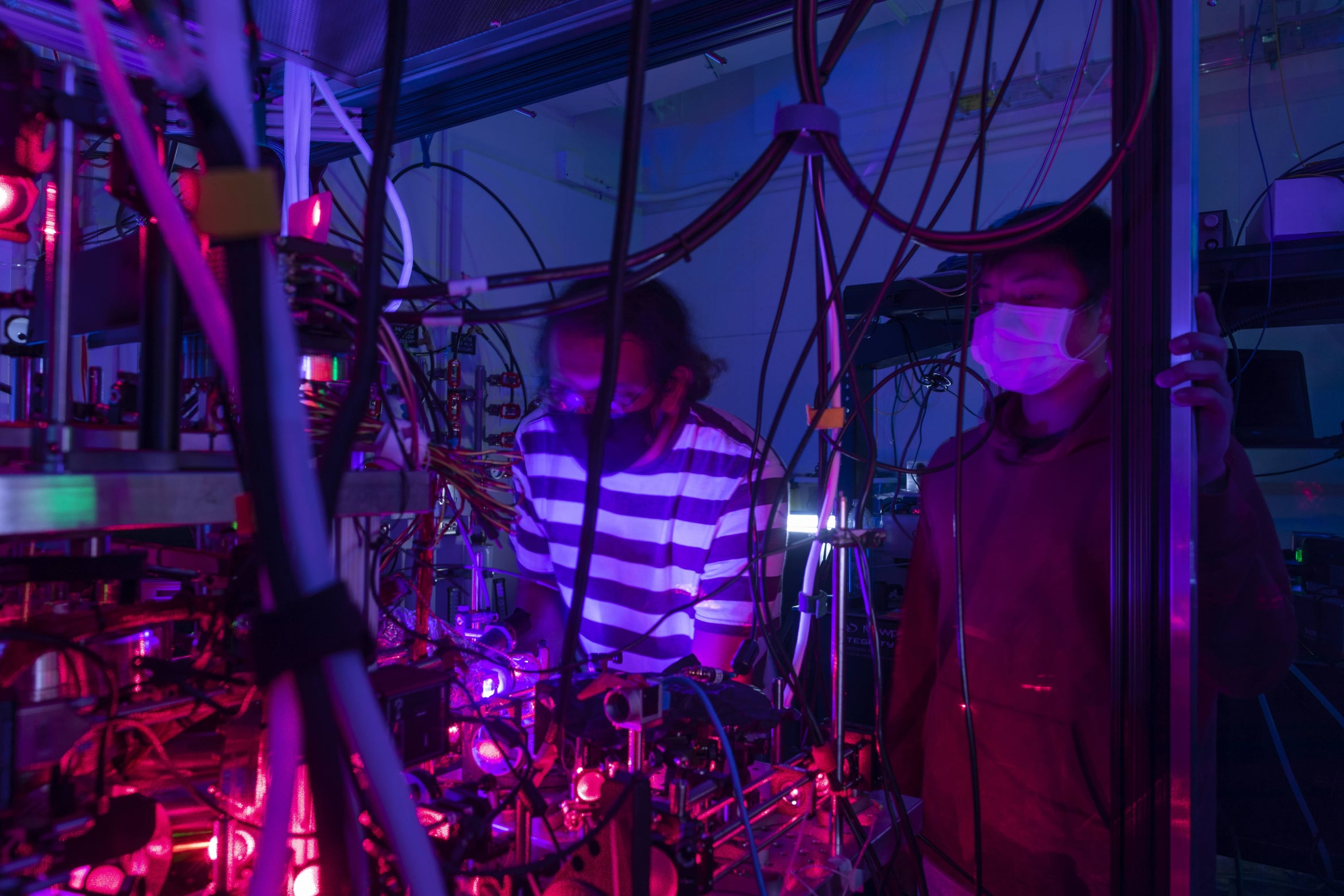

“To solve this problem required us to build p-computers at sizes we had never gone to before,” Çamsarı said, “We used millions of p-bits and then did simulations on CPUs to see how they will behave at much larger scales, using existing chips that we customize.”

The idea to use so many p-bits came accidentally. Two Ph.D. students from the University of Messina, in Italy — Andrea Grimaldi who was visiting the Çamsari lab, and Eleonora Raimondo, who was in Messina — began to see non-intuitive favorable behavior while working with very large numbers of p-bits. “It took a year or so to understand and develop a theory for why having lots of p-bits in parallel improves performance in such an unexpected way,” Chowdhury recalled. “Then, we wondered, ‘Can we build it?’ So, we got more collaborators to work on the paper and their collective opinion was, ‘Yes, in principle, this chip will work.’”

Chowdhury spent two years on the project. The result was the paper establishing that, when co-designed with hardware to implement powerful Monte Carlo algorithms, a p-computer provides a compelling and scalable classical pathway for solving hard optimization problems.

Focusing on two key algorithms applied to 3D spin glasses — discrete-time simulated quantum annealing and adaptive parallel tempering — the researchers showed that the p-computer outperformed a leading quantum annealer on the same problems. They further demonstrated, the team writes, that “These algorithms are readily implementable using currently available hardware, suggesting that specialized chips can leverage massive parallelism to accelerate these algorithms by orders of magnitude while drastically improving energy efficiency. Our results establish a new and rigorous classical baseline, clarifying the landscape for assessing a practical quantum advantage.”

“We previously had a chip with tens of thousands of p-bits, but modern semiconductor technology makes it possible to build one that can house millions of p-bits,” Çamsari explaineds. “By working with chip designers as part of our team and doing simulations, we showed that superior results could be achieved with a 3 million-p-bit chip that TSMC, a chip company in Taiwan, could build today. We simulated this chip and have 100% trust in the simulation that shows that it can be made with existing technology.”

“We had never run a problem that large,” Çamsari saidnotes. “Once we did, the question was whether a quantum machine solves it better than any other approach. The answer, from our research, is no.”