UC Santa Barbara researchers are working to move cold atom quantum experiments and applications from the laboratory tabletop to chip-based systems, opening new possibilities for sensing, precision timekeeping, quantum computing and fundamental science measurements.

“We’re at the tipping point,” said electrical and computer engineering professor Daniel Blumenthal.

In an invited article that was also selected for the cover of Optica Quantum, Blumenthal, along with graduate student researcher Andrei Isichenko and postdoctoral researcher Nitesh Chauhan, lays out the latest developments and future directions for trapping and cooling the atoms that are fundamental to these experiments — and that will bring them to devices that fit in the palm of your hand.

Cold atoms are atoms that have been cooled to very low temperatures, below 1 mK, reducing their motion to a very low energy regime where quantum effects emerge. This makes them sensitive to some of the faintest electromagnetic signals and fundamental particles, as well as ideal timekeeping, navigation devices and quantum “qubits” for computing.

In order to capitalize on these properties, many researchers currently work with highly sensitive laboratory-scale atomic optical systems to confine, trap and cool the atoms. Conventionally, these systems use free-space lasers and optics, generating beams that are guided, directed and manipulated by lenses, mirrors and modulators. These optical systems are combined with magnetic coils and atoms in a vacuum to create cold atoms using the ubiquitous 3-dimensional magneto-optical trap (3D-MOT). The challenge that researchers face is how to replicate the laser and optics functions onto a small, durable device that could be deployed outside of the highly controlled environment of the lab, for applications such as gravitational sensing, precision timekeeping and metrology, and quantum computing.

The Optica Quantum review article covers recent and rapid advancements in the realm of miniaturizing complex cold-atom experiments via applications of compact optics and integrated photonics. The authors reference photonics achievements across a variety of sub-fields, ranging from telecommunications to sensors, and map the technology development to cold atom science.

“There’s been a lot of really great work miniaturizing beam delivery,” said Isichenko, “but it’s been done with components that are still considered free-space optics — smaller mirrors or smaller gratings — but you still couldn’t integrate multiple functionalities onto a chip.”

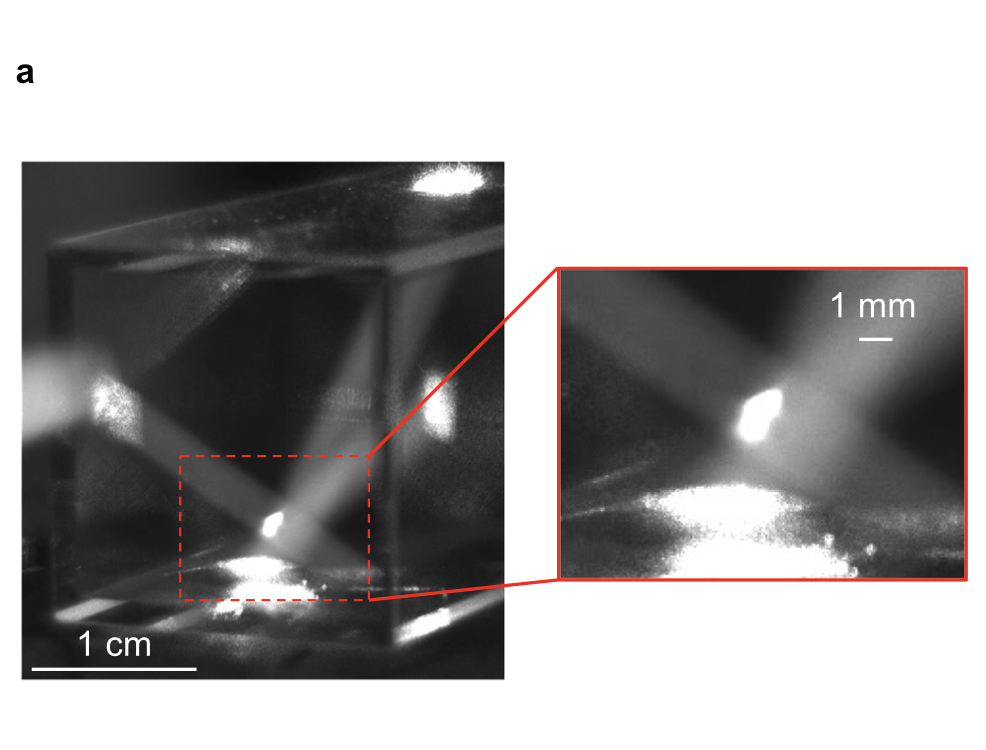

Enter the researchers’ photonic integrated 3D-MOT, a miniaturized version of equipment used widely in experiments to deliver beams of light to laser cool the atoms. Embedded into a low-loss silicon nitride waveguide integration platform, it’s the part of a photonic system that generates, routes, expands and manipulates all the beams necessary to trap and cool the atoms. The review article highlights the photonic integrated 3D-MOT — or “PICMOT” demonstrated by the UC Santa Barbara team as a major milestone for the field.

“With photonics, we can make lasers on chip, modulators on chip and now large-area grating emitters, which is what we use to get light on and off the chip,” Isichenko added.

Of particular interest is the atomic cell, a vacuum chamber where the atoms are trapped and cooled. One feat the researchers accomplished was to route the input light from an optical fiber, which is less than the width of a hair, via waveguides to three grating emitters that generate three collimated free-space intersecting beams 3.5 mm wide. Each beam is reflected back on itself for a total of six intersecting beams that trap a million atoms from the vapor inside the cell and, in combination with magnetic fields, cool the atoms to a temperature of

just 250 uK. The larger the beams the more atoms can be trapped into a cloud and interrogated, Blumenthal noted, and the more precise an instrument can be.

“We created cold atoms with integrated photonics for the first time,” said Blumenthal.

The implications of the researchers’ innovations are far-reaching. With planned improvements to durability and functionality, future chip-scale MOT designs can take advantage of a menu of photonic components, including recent results with chip-scale lasers. This can be used to optimize technology for applications as diverse as measuring volcanic activity to the effects of sea level rise and glacier movement by sensing the gradient of gravity on and around the Earth.

Integration of the 3D-MOT can give quantum scientists and time keepers new ways to send today’s earthbound instruments into space and conduct new fundamental science, and enable measurements not possible on Earth. Additionally, the devices could advance research projects by decreasing the time and effort spent establishing and fine tuning optical setups. They can also open the door to accessible quantum research projects for future physicists.