Television in the 1950s is broadly synonymous with bland conformity. Popular programs painted a benign portrait of nuclear families — wholesome, suburban and, of course, white. Newscasts were heavy on the threat of Communism, light on internal issues such as inequality.

As a scholar of the Cold War era, Carole Stabile found herself asking how this came to be. Her intriguing conclusion: The uninspired uniformity can be traced to the infamous Hollywood blacklist.

As the incoming Trump administration threatens television networks with lawsuits and possible criminal investigations, it is useful to revisit that dark period roughly 75 years ago, when intimidation of media companies was common and effective. Stabile, a media history professor and dean of the University of Oregon’s Robert D. Clark Honors College, will bring two noteworthy CBS broadcasts from that fraught era to UC Santa Barbara’s Pollock Theater on Jan. 16th.

At the screening, Patrice Petro, a professor of film and media studies and Dick Wolf Director of the Carsey-Wolf Center, will interview Stabile about the blacklist’s origins and ramifications. The program, which is free to attend (reservations are suggested), is part of the ongoing “Panic!” series, which Petro describes as “an exploration of films and television shows that addressed the turbulent relations between social, cultural and moral panic in the past — and in our own time.”

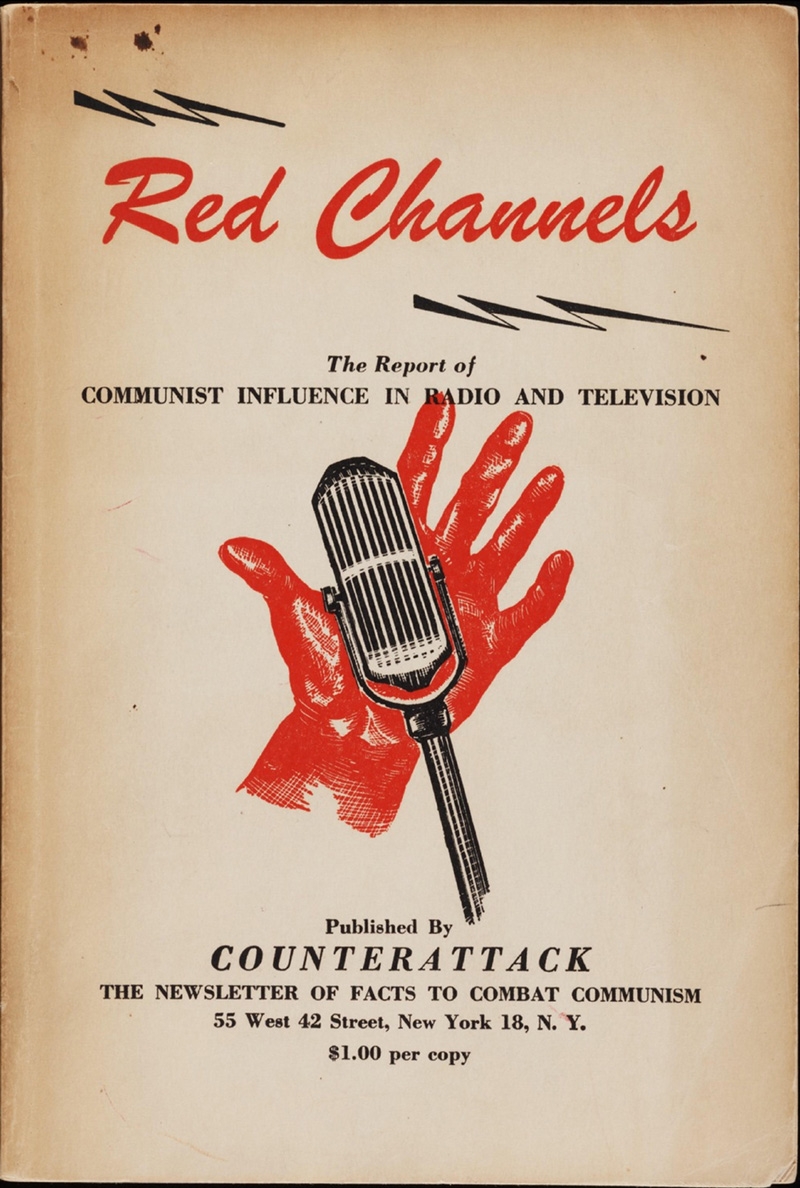

In the late 1940s and through most of the 1950s, movie studios and television networks were frightened into complying with what has become known as the Hollywood blacklist. Independent organizations, working in loose coordination with J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, compiled lists of writers, directors and actors who were alleged to be members of the Communist Party or radical leftist sympathizers (the so-called “fellow travelers”).

By threatening boycotts, they managed to intimidate some of Hollywood’s most powerful entities into firing, or refusing to hire, artists on their lists of “subversives.” Countless careers were disrupted or destroyed.

By the late 1940s, “The FBI was really worried about television — who would be in control of this new medium,” Stabile explained. Hoover and his team were particularly wary of CBS, which they referred to as the “Communist Broadcasting System” in internal documents.

Working with such varied associates as right-wing congressmen, the American Legion, and the Catholic Church, the FBI “mobilized many points of pressure” against entities that were labeled as leftist, according to Stabile. “These groups would threaten boycotts against the networks or sponsors if they continued to employ workers who were identified as Communists or fellow travelers.”

In this atmosphere, it was easy to label as “Communist” pretty much any actor, writer or director whose ideology was left of center and could, at least in theory, inject these “un-American” ideas into the public discourse through their work. (It was also easy to get revenge on a disliked superior or colleague.) The result was a culling of provocative voices, and a strong incentive to avoid questioning the status quo.

Stabile chose two programs to illustrate this dynamic. The first is a 1943 radio essay that producer William N. Robson wrote and directed in response to racial unrest in Detroit. He won a Peabody Award for the program, which the organization calls an “open letter” that “argued with dramatic simplicity and force for the futility of violence as a solution to racial problems.”

How did an eloquent call for nonviolence get construed as somehow radical or dangerous? The FBI and its allies “saw anything that was at all critical about race relations in the U.S. as evidence of Communist infiltration,” Stabile said. “So it didn’t matter what he said.”

Robson was fired from CBS in late 1950, and his influence and stature in the industry was reduced as the red scare intensified. He concluded his impressive career at the Voice of America. His “Open Letter on Race Hatred” suggests that, before the blacklist, CBS was a place where journalists had more freedom to express uncomfortable ideas openly — not exactly a hallmark of its 1950s programming.

(One notable exception was Edward R. Murrow’s famous 1954 takedown of Sen. Joseph McCarthy. Stabile suspects Murrow’s stature as America’s foremost broadcast journalist, forged during his World War II broadcasts, gave him some protection against the blacklist.)

The second program Stabile is showing is a 1951 episode of the long-running sitcom “The Goldbergs,” which made a successful transition from radio to television. It features creator and writer Gertrude Berg, guest star Anne Bancroft and series regular Philip Loeb, who was fired not long after the episode aired. He committed suicide in 1954.

“Loeb, who was one of the founders of Actors Equity, had been a target of the anti-Communist press throughout the 1940s, although he was not a member of the party,” Stabile said. “Berg was also unpopular among this group, which was highly antisemitic as well as racist. They didn’t like the fact she was a powerful woman who had a big fan base.”

Like Robson’s audio essay, “The Goldbergs” illustrates how different television was before the blacklist. In it, “you have a family speaking heavily accented English, living in a tenement in the Bronx,” Stabile noted. “Berg was broadcasting narratives about ethnic life and forms of diversity that would become far less common after the blacklist took hold.”

While thinking about how television might have been different, and better, if the blacklist hadn’t happened is a fascinating exercise, the stories of Robson and Loeb also have present-day ramifications. Once again, Stabile noted, we appear to be witnessing attempts to intimidate the heads of major media organizations into passivity.

“I think it’s helpful to know that it’s not the first time that forces in the United States have tried to redefine what it means to be an American,” Stabile said. “These forms of retaliation and suppression of dissent are not unprecedented.

“Perhaps by understanding the playbook, we can do a better job of preserving free speech.”