Historian Tsuyoshi Hasegawa writes definitive account of the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II

The Romanov family rose to imperial power in Russia in the early 1600s, its rule passed down for more than 300 years until the compounding crises of World War I, political turmoil and public pushback against the regime led to its violent end. But it wasn’t the sword of fate that struck down Imperial Russia as much as its “blinkered faith in autocracy” and the inept leadership of Tsar Nicholas II, the last ruler of the Romanov dynasty.

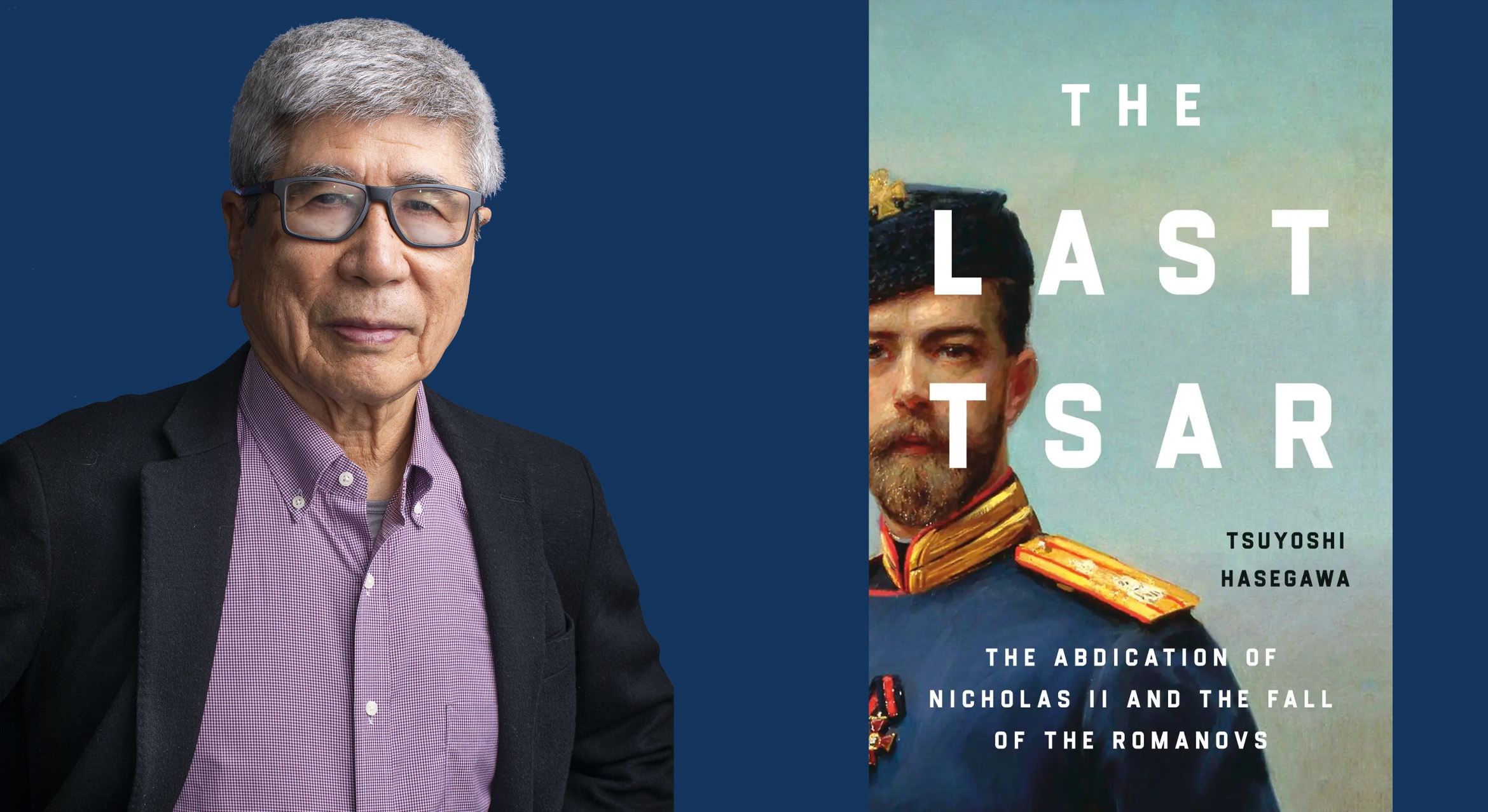

In his newly released book, “The Last Tsar: the Abdication of Nicholas II and the End of the Romanovs" (Basic Books), author Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, an emeritus professor of history at UC Santa Barbara, closely narrates the tumultuous backdrop and captivating personalities of the last tsar’s undoing — Nicholas and his family were executed by the Bolsheviks in 1918.

An expert on modern Russian/Soviet history, Hasegawa provides a detailed account of how Nicholas II’s poor leadership and attachment to archaic notions of autocracy led to the end of the Romanov dynasty. The book also brings to life the bumbling Nicholas, his spiteful wife and the family’s faith healer, Rasputin, as it untangles the dramatic struggle by Russia’s aristocratic, military and legislative elite to stem the tide of revolution by demanding Nicholas’s concessions during the February Revolution of 1917. Under their pressure, Nicholas was forced to abdicate not only for himself but for his son, a decision that led to the end of three centuries of Romanov rule.

Included among the books of the year by History Today, “The Last Tsar” is “essentially a forensic study of the last week of Tsar Nicholas II’s reign and the shenanigans of grand dukes, generals, parliamentarians and officials by which his train, and his reign, were brought to a halt.”

Robert Service, author of “A History of Modern Russia: From Tsarism to the Twenty-First Century” (Harvard University Press, 2009), praised Hasegawa’s account for “knock(ing) down many of the pillars of our usual interpretations” of the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Hasegawa’s scholarship on the subject dates to the 1960s. As an undergraduate at Tokyo University, his senior thesis at the University of Tokyo would later serve as a jumping off point for his first book, “The February Revolution: Petrograd, 1917” (University of Washington Press, Seattle). Decades later, “prompted by the changing world, as well as by new scholarship and new sources,” he returned the history to publish a revised edition in 2017.

Since then, he said, “the world has been going through a new challenge — the rise of authoritarianism globally,” a trend that has impacted democracy worldwide.

“I went back to reexamine the vigorous debates among Russian historians about Nicholas II’s abdication and sources that I had overlooked,” he said. “I also benefited a great deal from new research” for this newest volume.

“This book is the fulfillment of a dream to tell the full story of the abdication drama that ended the tsarist autocratic system,” he said.