The exiles who shaped the contours of modern dance

The experience of exile, whether literal or symbolic, is inevitably reflected in an individual’s body. Feeling cut off from one’s roots, or viewing yourself as a stranger in a foreign land, influences how one stands, walks and moves.

Modern dance in the United States, the land of immigrants, is rooted in precisely this form of physical expression. That’s the thesis of “Border Crossings: Exile and American Modern Dance 1900-1955,” a major exhibition running Jan. 25 through May 7 at UC Santa Barbara’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum.

“War, inequality and injustice shaped 20th century performance art,” explained curator and Professor Ninotchka Bennahum. “The exhibition rests on the idea that the immigrant, the asylum seeker, the exiled artist, shaped the language of dance modernism. The act of crossing borders, the nature of exile, initiated aesthetic philosophies which translated into choreography.”

“The impulse,” said UC Santa Barbara Professor Emeritus Bruce Robertson, “was to think about modernism in American dance in the context of bodily displacement — literally moving from one country to another, or moving across internal borders, such as from South to North.”

As Rena Heinrich of the University of Southern California said, “there is truth in the body.” The movements dancers make, and choreographers create, inevitably reflect their “embodied experience.” For many of the pioneers of American dance, one such embodied experience was the act of crossing a border.

“For example, Mexican-born choreographer José Limón fled the violence of the Mexican revolution with his family in 1915, crossing into the U.S. at the Nogales border,” Bennahum noted. “Despite growing up in L.A. and rising to prominence as one of the greatest male modern dancers of his generation, Limón did not gain U.S. citizenship until 1946."

Whether they were escaping violence in Latin America, emigrating from Europe due to anti-semitism, or moving from one region of the U.S. to another to get away from virulent racism, these émigré artists were all looking for sanctuary.

They found it, at least to a degree, in their new homes. And they found ways of telling their stories by entering a sanctuary of a different type: The dance studio. In the process, they invited a movement vocabulary that is still in use today.

“This story has been overlooked by modern dance studies for a long time,” Heinrich added. “This exhibition is intended to push it to the front.”

“Border Crossings” debuted in 2023 at the New York Public Library, where it was co-curated by Bennahum, a professor of dance studies, and Bruce Robertson, director emeritus of the AD&A Museum and a professor emeritus of the history of art and architecture. Bennahum curated the UC Santa Barbara show, which has been slightly reconfigured to focus more on West Coast artists, with Heinrich, who was part of a community of artists and scholars who consulted on the New York show.

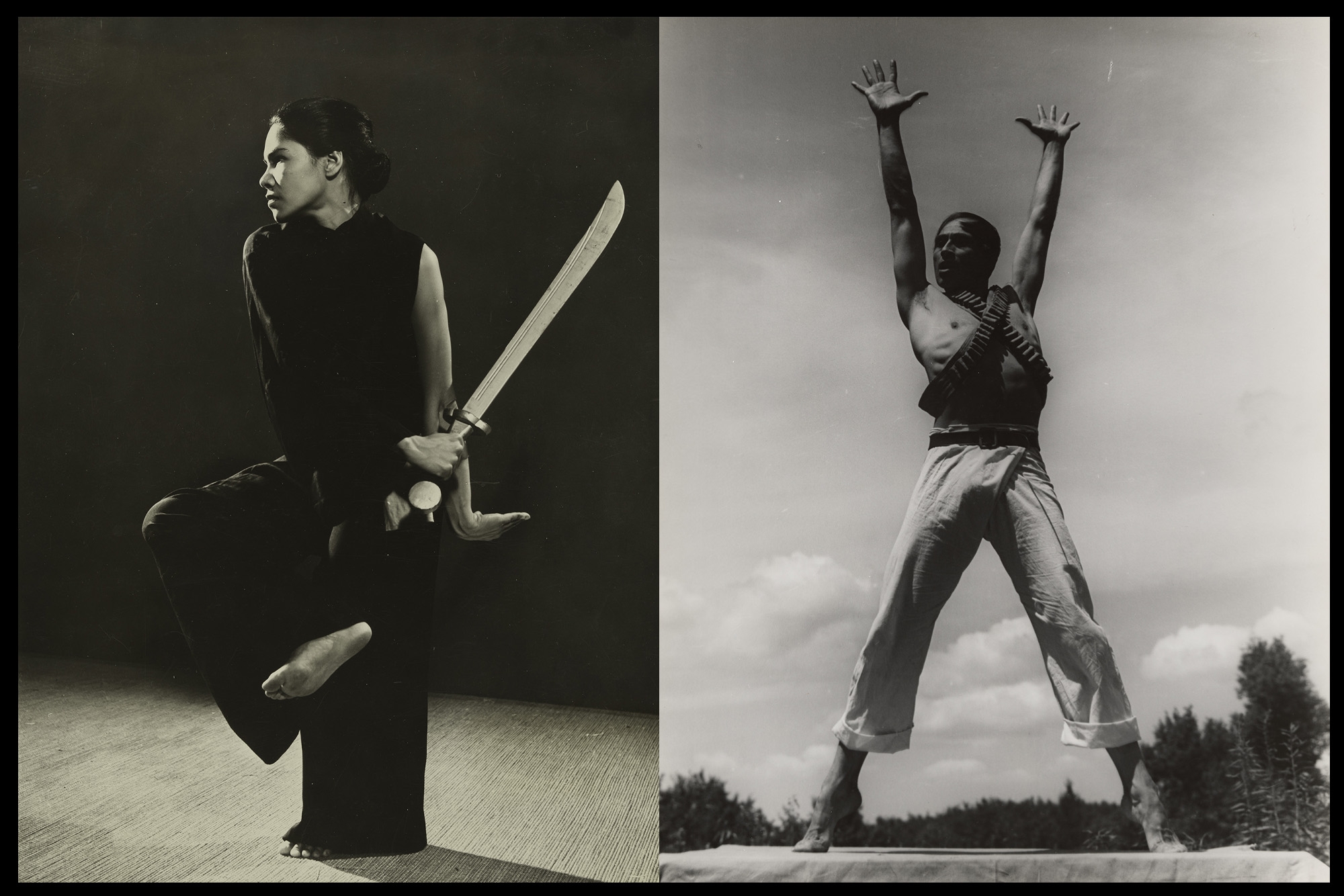

The exhibit contains works in a variety of mediums, including costumes, artwork, print media and still photographs from the period. They reveal two key things: American modern dance companies in the pre-World War II age were far more racially and ethnically integrated than one might imagine, and many of the works they presented had social or political themes.

“Martha Graham, who grew up in Santa Barbara, was influenced by radical artists such as Russian émigré Benjamin Zemach and Japanese-born Michio Ito,” Bennahum said. “In the 1930s she created contemporary works that spoke directly to the struggles of the day: the Great Depression is evidenced in Graham’s Steps in the Street, a dance about hunger.

“Graham, shown through the lens of Japanese photographer Soichi Sunami, exhibits a political point of view. In ‘Vision of the Apocalypse,’ the viewer witnesses an individual facing a street mob."

A film shows Pearl Primus’s “Strange Fruit” from 1943, in which a dancer performs the role of a white male spectator who has just witnessed a lynching. There are also photos of a dance from the 1930s about the struggles of a homeless woman. They provide “evidence of the power of the dancing body to deliver these messages,” she said.

Three costumes are on display, along with what Bennahum calls “rare filmography, with excerpts from dozens of films shown on multiple monitors. This is material that would be very hard to see otherwise. It’s a Manifesto of the Unsung — a record of movement that bears witness to trauma — but also to courage, resilience and complex artistry.”

The exhibit’s opening weekend will feature a two-day symposium and two public performances: A visit by the Jose Limón Dance Company Jan. 27 at Campbell Hall, presented by UCSB Arts & Lectures, and a recital at 3 p.m. Jan. 28 in the campus’s Hatlen Theater featuring that internationally renowned troupe, plus the Santa Barbara Dance Theater and UCSB Dance Company.

The Sunday afternoon performance, which is open to the public, complements the exhibit’s themes “with a nod to legacy and generational perspectives,” said Brandon Whited, director of dance performance at UC Santa Barbara, and artistic director of Santa Barbara Dance Theater.

He noted that the “UCSB dance company’s repertory offers the students a connection to historical works with the opportunity to learn from Alice Condodina,” a professor emeritus of dance and former principal dancer with the Limón company. Similarly, “Santa Barbara Dance Theater’s repertory selections consist of new and recent works by choreographers with a direct connection back to Limón Dance Company, and representing the artists’ personal resonances on migration and cultural adaptation within personal family histories.”

Like those performances, the exhibit is aimed at two audiences: The general public, and the dance community. The former “tends to think of modern dance as abstract,” Robertson noted. “This shows that, since its beginnings, it has been rich and surprising (in its choice of themes).”

For the latter, the exhibit “shows younger dancers and choreographers that there’s a century-old history” of multicultural, politically aware performance art. “One big takeaway for them is: You’re not inventing something out of thin air. You have a rich tradition to play with.”

Heinrich agreed. “If you’re part of a group that feels disenfranchised, making art can feel like a very tall hill to climb,” she noted. “I hope this show shows those folks, ‘Your place has been carved out for you. You can build on that.

“It’s important for young artists to know that they not only have a place in the field—they have always had a place in the field.”

Debra Herrick

Associate Editorial Director

(805) 893-2191

debraherrick@ucsb.edu