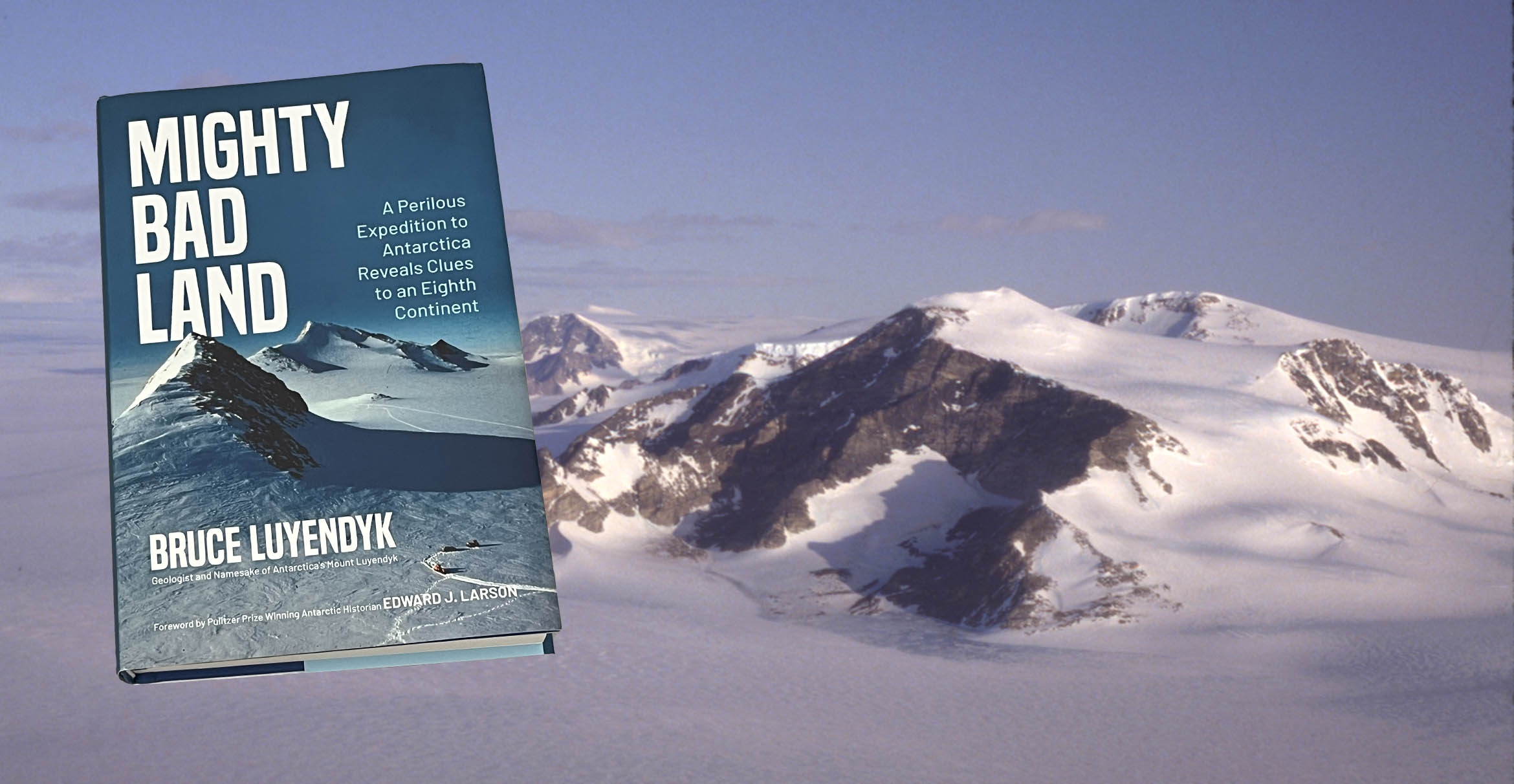

In an age where exploration seems long since passed, geology professor Bruce Luyendyk presents a modern story of research and adventure. His memoir “Mighty Bad Land” (Permuted Press, 2023) chronicles his first expedition of many to the frozen reaches of Marie Byrd Land to uncover how the southern supercontinent broke apart. Working beyond the reach of helicopter rescue, his team braved whiteouts, deep crevasses and interpersonal conflict much like the pioneering explorers of the inhospitable Antarctic interior.

The geologic history of Antarctica was far from Luyendyk’s first academic interest. He was already widely traveled when he joined the faculty at UC Santa Barbara and began researching the landscape of California. He was soon joining expeditions to New Zealand, which had certain geologic parallels with the west coast of the United States. Eventually, he and his collaborator Dave Kimbrough realized that answering their questions about New Zealand would require a voyage to Antarctica. One thing led to another, which led to another, until one cold day in December 1989 Luyendyk stepped out of a cargo plane into the Antarctic wilderness.

The author found himself at the bottom of the Earth at the cusp of the internet era, during a gap between the efforts of the Cold War and the fully connected information age. Outposts and infrastructure were already well established, but isolation still pervaded Antarctic research. “This was a transitional time that hasn’t gotten much exposure,” said Luyendyk, a veteran of nine Antarctic expeditions. “None of the other scientists were inclined to write a book like this, so I figured I’ll learn how to write, and I’ll tell a new story.”

The seasoned scientist went back to class and developed an engaging writing style. His tone is at once direct and poetic, describing in relatable detail the scenes and characters of his story, and the thoughts in his head, while vividly capturing the terrifying and majestic wasteland in which it takes place.

Luyendyk tackles topics like his relationships, anxieties and family trauma with unvarnished candor. “You just can’t hide stuff if you’re going to write a memoir,” he said, recalling advice from his writing instructor. “If you do, it’s not a memoir; it’s some other story.

“You get judged, of course,” he continued. “But what’s worse: being judged for BS-ing or telling the truth?”

Fortunately, the simple truth is more than enough when talking about Antarctica. “Nobody makes anything up about down there,” Luyendyk said. “You don’t have to.” The work is hard and the continent, mercurial. One day you might make great progress under the southern summer sun, while the next could be a total whiteout: no land, no sky, no horizon; just a team and their gear suspended in a glass of milk. Fierce storms held up progress for days as the group hunkered down in their polar tents.

“What you know is you’re alone. That’s what you know,” Luyendyk said. “Even six people, we’re alone. Alone together.”

As the leader of this first expedition, he also felt alone in his responsibility. His duty for the success of the mission, the safety of the team and the results of their research.

Perhaps his favorite summary of the book, he noted, came from an Amazon review: “Each person had something valuable to teach me through the eyes of their very real and not-always-fearless-leader.”

“I said to myself, ‘That is true. And you know what? Being in Antarctica, that’s a real asset,’” Luyendyk remarked. “Because if you’re not a little anxious, if you’re not a little frightened, you’re going to get yourself into trouble you can’t get out of.”

Luyendyk learned to channel his fear into his work rather than let it control him. “The thing is, you don’t get rescued in Antarctica,” he said. “You have to rescue yourself. That’s what makes it really dangerous.”

Yet despite the peril, the discomfort and isolation, Luyendyk returned time and again to the frozen continent and its surrounding seas. “You feel kind of good after you’ve done something really hard,” he said. “I think everybody knows that.

“Why do easy stuff?” he added. “There’s no reward in that, personally or professionally.” The book illustrates how hard researchers will push themselves in pursuit of answers, the individual passion that drives the scientific enterprise.

Antarctic research epitomizes this ethos. “It’s a place where there are still places that people haven’t visited, still questions that haven’t been looked at,” Luyendyk said. “The sense of discovery hooks you in, and you find yourself returning despite the isolation, danger and discomfort.”

And not everyone has an opportunity to journey to Antarctica. You need to have business down there to be cleared to visit. “It’s a unique privilege,” he said. “I’m lucky we got some good science out of it.”

That “good science” was a comprehensive account of how New Zealand separated from Antarctica during the breakup of the southern supercontinent Gondwana. Luyendyk and his colleagues answered questions like why the crust of Marie Byrd Land rose while New Zealand sank He later coined the term “Zealandia” for the extensive submerged continent of which New Zealand is the summit. He summarizes the scientific findings in an appendix for readers eager to learn how things panned out.

Even after nine expeditions, Luyendyk said he’d still return if he could, perhaps as a writer this time. He’d love an opportunity to capture the eccentricity, dedication and skill of the folks who venture to the southern continent, and the community that forms around them.

“It’s not for everybody, of course,” he said. But an accomplishment down there hits differently. “You feel like, ‘That was tough, but we did good; we did fine. Let’s do that again.”

Harrison Tasoff

Science Writer

(805) 893-7220

harrisontasoff@ucsb.edu