Political science professor examines democracy in America in special issue on Black Lives Matter

Some people say the United States is the oldest continuous democracy.

Not so, argues political scientist Christopher Parker.

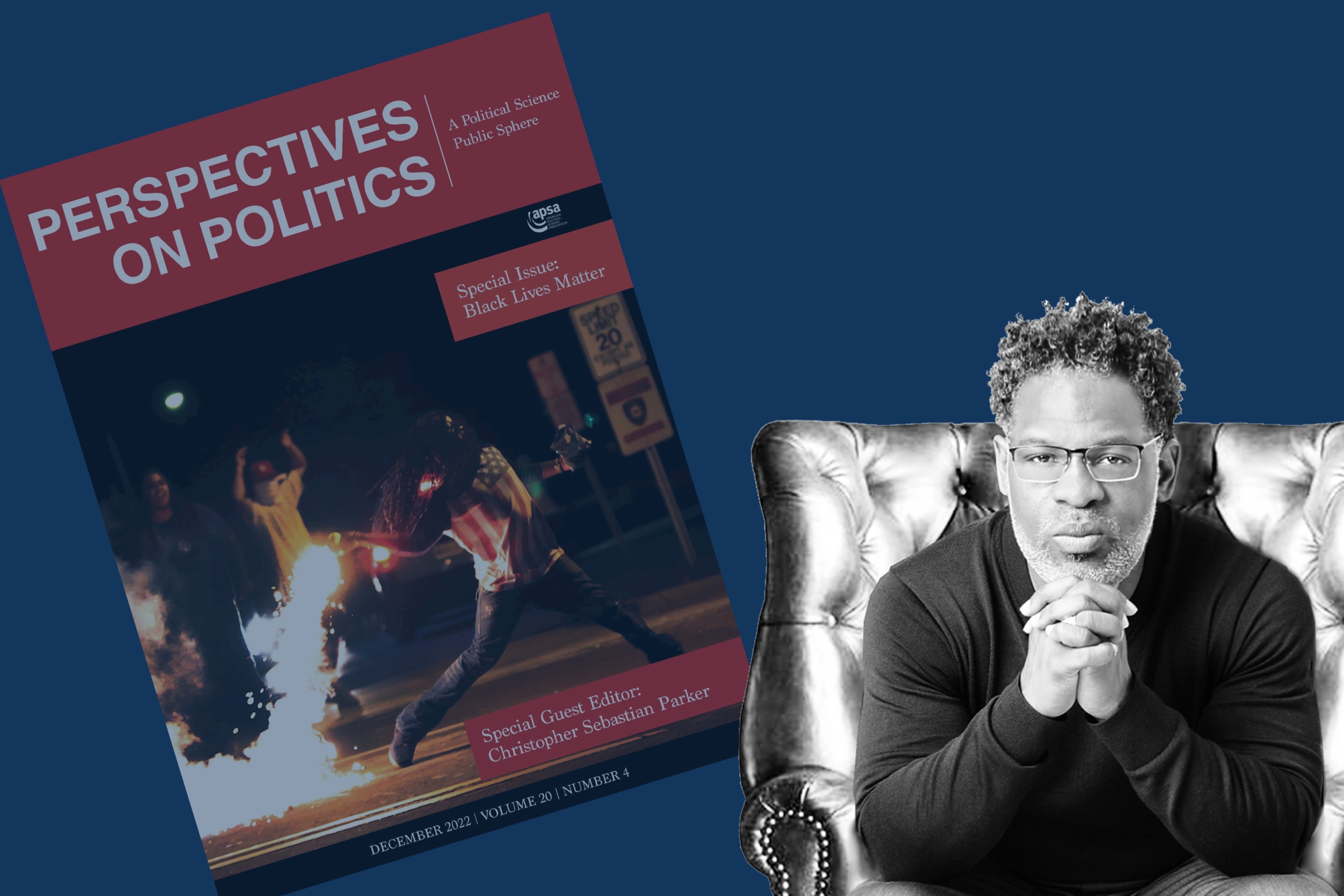

“That’s only if you don’t count slavery and the Jim Crow South where you have a third of the country basically under authoritarian rule — and that’s from the country’s founding until the Voting Rights Act of 1965,” said Parker, a political science professor at UC Santa Barbara and the editor of a special issue on Black Lives Matter in the journal Perspectives on Politics. “’American democracy’ is this idea that people like me — Black folks — weren’t initially included in, and institutions weren’t set up for us to be either; and yet, we were made to bear the burden of sustaining it, even fighting for it during war.”

By addressing Black Lives Matter (BLM) cover-to-cover in a highly-regarded, peer-reviewed journal in political science, Parker hopes the contemporary civil rights movement will garner more attention from the discipline where it’s often marginalized in favor of more “mainstream” political science.

BLM is about preserving Black lives, acknowledged Parker, whose first book, “Fighting for Democracy: Black Veterans and the Struggle Against White Supremacy in the Postwar South” (Princeton University Press, 2009), won the American Political Science Association’s Ralph J. Bunche Award. But he, himself a veteran of the U.S. Navy and Naval Reserve, also pointed out that the movement confronts systems of injustice that exploit people of color, exposing how race and racism still play out across institutions, such as the criminal justice system, the armed forces and elections.

As a movement, BLM sprang up in 2012 in response to the murder of Trayvon Martin, and the acquittal of his assailant. It later achieved historical levels of support after the police killing of George Floyd in 2020.

Even so, Parker said there has been an unwillingness to investigate Black rights within the institution of political science, a discipline he called the most conservative of the social sciences save economics. A few years ago, he started saying out loud that he wanted to see more analysis of the movement in the corridors of political science departments. By 2020, acting on his word, he proposed the special issue on BLM to his colleagues Michael Bernhard and Daniel I. O’Neill at the University of Florida, editors of Perspectives on Politics published by University of Cambridge Press.

“This is a major journal in political science and the issues surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement needs to be represented,” Parker said. “We need a space for this kind of work in one of the flagship journals of the discipline. It’s not going to happen in any of the other journals. This was the only one that I thought, ‘We have a shot to do this.’”

Articles in the special issue use qualitative, quantitative and interpretive methods to analyze BLM, police and community perspectives, the role of activists and the meaning of the movement. “The pieces included represent a collective attempt to make plain the extent to which race (and racism) are, at once, a threat to American democracy and a necessary condition for American democracy to ‘work,’” Parker writes in his letter from the editor, “An American Paradox: Progress or Regress? BLM, Race, and Black Politics.”

In a multiracial democracy, explained Parker, there would be a universal application of the American values of life, liberty, equality and tolerance. “Black people are still fighting for voting rights,” he said, noting that last year the Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act collapsed in Congress. The new voting legislation would have made Election Day a national holiday, ensured access to early voting and mail-in ballots and enabled the federal Justice Department to intervene when states attempted voter interference — all actions that would increase voter registration and access for Black constituents.

For Parker, this is just another example of how “the promise of multiracial democracy is consistently undermined by the practice of American democracy.”

“I’m a Black man in America. Can I afford to be optimistic? We’re disappointed at every turn. That’s the difference between Black folks and white folks,” he said. “We can’t afford to be optimistic because we are so often disappointed. They, whites, move the goal posts on us all the time.”

Debra Herrick

(805) 893-5446

debraherrick@ucsb.edu