Eruption’s Echoes

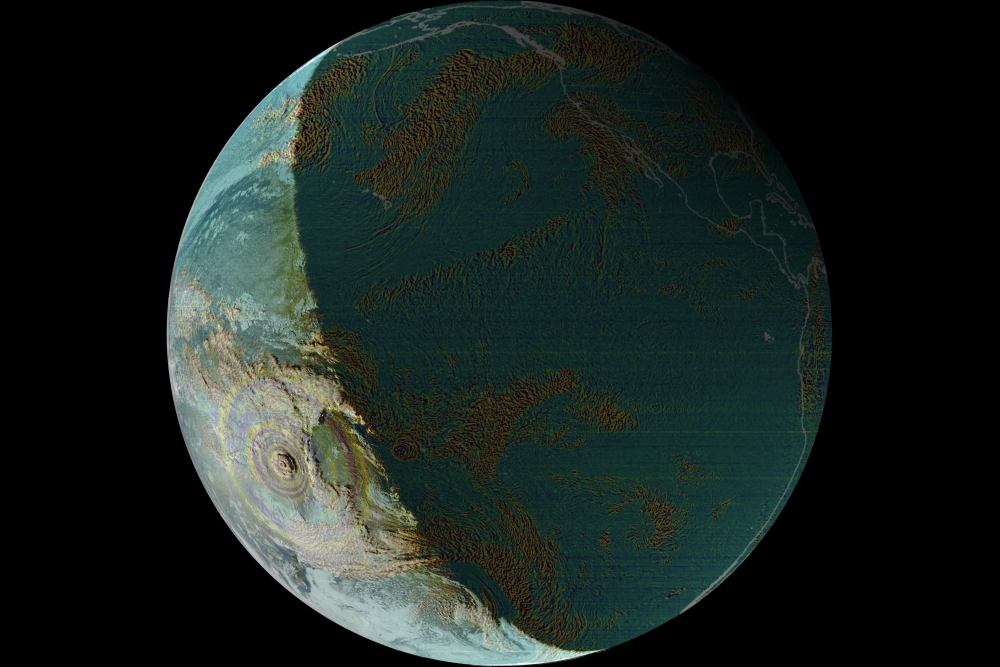

The Hunga volcano ushered in 2022 with a bang, devastating the island nation of Tonga and sending aid agencies, and Earth scientists, into a flurry of activity. It had been nearly 140 years since an eruption of this scale shook the Earth.

UC Santa Barbara’s Robin Matoza led a team of 76 scientists, from 17 nations, to characterize the eruption’s atmospheric waves, the strongest recorded from a volcano since the 1883 Krakatau eruption. The team’s work, compiled in an unusually short amount of time, details the size of the waves originating from the eruption, which the authors found were on par with those from Krakatau. The data also provides exceptional resolution of the evolving wavefield compared to what was available from the historic event. The paper, published in the journal Science, is the first comprehensive account of the eruption’s atmospheric waves.

Early evidence suggests that an eruption Jan. 14 sunk the volcano’s main vent below sea level, priming the massive explosion the following day. The Jan. 15 eruption generated a variety of different atmospheric waves, including booms heard 6,200 miles away in Alaska. It also created a pulse that caused the unusual occurrence of a tsunami-like disturbance an hour before the actual seismically driven tsunami began.

“This atmospheric waves event was unprecedented in the modern geophysical record,” said lead author Matoza, an associate professor at UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Earth Science.

The Hunga volcanic eruption has provided unprecedented insight into the behavior of a variety of atmospheric wave types. “The atmospheric waves were recorded globally across a wide frequency band,” said co-author David Fee at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute. “And by studying this remarkable dataset we will better understand acoustic and atmospheric wave generation, propagation and recording.

“This has implications for monitoring nuclear explosions, volcanoes, earthquakes and a variety of other phenomena,” Fee continued. “Our hope is that we will be better able to monitor volcanic eruptions and tsunamis by understanding the atmospheric waves from this eruption.”

The researchers were most interested in the behavior of an atmospheric wave known as a Lamb wave, which is the dominant pressure wave produced by the eruption. These are longitudinal pressure waves, much like sound waves, but of particularly low frequency. Such low frequency, in fact, that the effects of gravity must be taken into account. Lamb waves are associated with the largest atmospheric explosions, such as large eruptions and nuclear detonations, though the wave characteristics differ between these two sources. They can last from minutes to several hours.

After the eruption, the waves traveled along Earth’s surface and circled the planet in one direction four times and in the opposite direction three times, the authors recorded. This was the same as scientists observed in the 1883 Krakatau eruption. The Lamb wave also reached into Earth’s ionosphere, rising at 700 mph to an altitude of about 280 miles.

“Lamb waves are rare. We have very few high-quality observations of them,” Fee said. “By understanding the Lamb wave, we can better understand the source and eruption. It is linked to the tsunami and volcanic plume generation and is also likely related to the higher-frequency infrasound and acoustic waves from the eruption.”

The Lamb wave consisted of at least two pulses near the volcano. The first had a seven- to 10-minute pressure increase followed by a second and larger compression and subsequent long pressure decrease.

A major difference between the accounts of Hunga’s Lamb waves versus Krakatau’s is the amount and quality of data scientists were able to gather. “We have more than a century of advances in instrumentation technology and global sensor density,” Matoza said. “So the 2022 Hunga event provided an unparalleled global dataset for an explosion event of this size.”

Scientists noted other findings about atmospheric waves associated with the eruption, including remarkable long-range infrasound — sounds too low in frequency to be heard by humans. Infrasound arrived after the Lamb wave and was followed by audible sounds in some regions.

Audible sounds reached Alaska, about 6,200 miles from the volcano, where they were heard around the state as repeated booms. “I heard the sounds,” Fee recalled, “but at the time definitely did not think it was from a volcanic eruption in the South Pacific.”

The scientists believe the sounds heard in Alaska couldn’t have originated in Hunga. While there’s still much to learn, it’s clear that standard sound models cannot explain how audible sounds propagated over such extreme distances. “We interpreted that they were generated somewhere along the path by nonlinear effects,” Matoza explained.

“There is a long list of possible follow-up studies examining the many different aspects of these signals in more detail,” he said. “As a community, we will be working further on this event for years.”

The paper's co-authors included UC Santa Barbara's Alex Iezzi, Hugo Ortiz and Rodrigo de Negri.

(This release was co-authored by Rod Boyce at University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute)