‘Theater for Social Change’

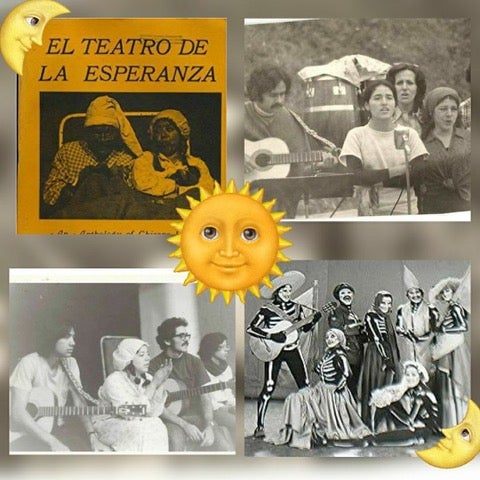

At UC Santa Barbara, as at many universities, the early 1970s are remembered as a period of conflict and strife. But something remarkable emerged from that tumultuous time: A new theater company created by Hispanic artists, for Hispanic audiences.

It was called El Teatro de la Esperanza — the Theater of Hope — and for more than a quarter-century, it promoted justice and inclusion through storytelling and music.

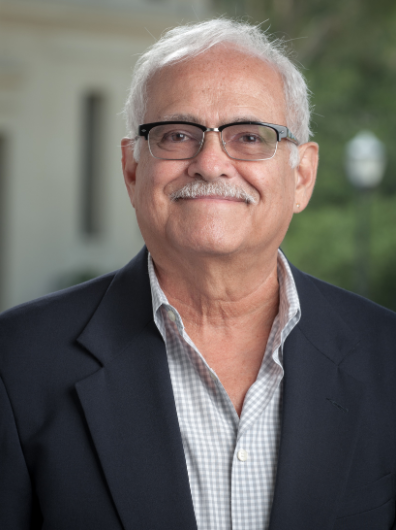

“It was theater for social change,” recalled Jorge Huerta, who founded the troupe while working towards his doctorate in the Department of Dramatic Art. “We would perform at high schools and community colleges. Those performances inspired a lot of people who had never seen themselves represented on stage.”

A pandemic-delayed conference marking the 50th anniversary of the company’s 1971 founding will take place from 1 p.m. to 6 p.m. Thursday, March 3 at the MultiCultural Center on campus. It is free and open to the public, and also will be livestreamed via Zoom.

The event will feature discussions about the company and its historical impact; excerpts from some of the actos, or short plays, it created and produced in its early years; and musical performances of the sort of songs that were incorporated into those productions.

Theater professor emeritus Carlos Morton, who organized the conference, called the troupe “an important part of the Chicano theater movement,” which was in its infancy in the early 1970s. Thanks in part to its pioneering efforts, he noted, “We now have a network of theaters all over the country.”

Huerta, who was a child actor in Hollywood in the 1950s, was working as a high-school drama teacher near Riverside when, in 1968, he saw a performance by the seminal troupe El Teatro Campesino. Founded by Luis Valdez in 1965 as an offshoot of Cesar Chavez’s farm workers union, it was touring the state with a program of short, consciousness-raising plays.

“I had never seen anything like it,” he recalled. “I said to myself, ‘This is what I have to do.’”

After visiting a friend who was pursuing a graduate degree in history at UCSB, he applied, and was accepted, to the university’s Ph.D. program in dramatic arts. Upon arrival, he assumed directorship of an ensemble that called itself Teatro Mecha, which was “mainly a folkloric dance group,” he said.

After much research and considerable trial-and-error, he began to mold the members into a theater troupe. In the style of El Teatro Campesino, the young actors performed and created work that reflected the issues they faced in their lives. But as the academic year went on, Huerta developed concerns about the larger organization the company was affiliated with, which was becoming more exclusionary.

When the troupe splintered in the spring of 1971, Huerta and his wife assumed leadership of the offshoot, El Teatro de la Esperanza. They chose the new community center La Casa de la Raza, on Santa Barbara’s heavily Hispanic East Side, as its home. Company members converted a space in the large building into a theater and began putting on shows.

“To go out in the community was a really bold and risky move,” said Morton. “They didn’t know what kind of reception they would get. But they had the moxie to strike out on their own.”

Huerta has many fond memories of those days, including self-publishing the company’s first collection of original short plays at the original Kinko’s copy shop. In time, the troupe started touring, and its shows were well-received — most of the time.

“One of the actos one of my students wrote was called Trapped Without Exit,” he recalled. It was about East L.A. and alleged abuses committed by the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department. Every other word was the f-word, which was how the gang members (the actors portrayed) talked.

“We did it at Santa Barbara High School. We didn’t warn anybody. By the third f-word, the principal jumped onto the stage and ordered the curtain to be lowered. In retrospect, I wish we had cut the foul language, which wasn’t really important. What was important is the fact they were killing poor people of color with impunity, and calling it suicide.”

The company’s most ambitious project in those early years was Guadalupe, which premiered in 1974. After reading about a dispute between Hispanic parents and school officials in that Santa Barbara County city, the troupe traveled to the area and interviewed the people involved about the discrimination and disrespect they faced on a daily basis.

“We attended mass at the Roman Catholic parish to hear what the priest, a Spanish missionary, had to say,” Huerta recalled. “Aware that we were in his church, he admonished his congregants, saying ‘Those of you who follow Cesar Chavez will go directly to hell!’”

The company subsequently fashioned a docudrama about the events, which received considerable acclaim and toured widely — including back to Guadalupe.

Another, even more ambitious work, La Victima, debuted two years later. That piece, which combined fact and fiction to dramatize the recurring issue of mass deportations in times of economic trouble, has stood the test of time: It was revived by the Latino Theatre Company of Los Angeles in 2019, in a production that toured schools throughout Southern California.

Huerta left El Teatro de la Esperanza in 1975, when he accepted a full-time professorship at UC San Diego. At some point in the 1980s, the troupe relocated to San Francisco. It continued producing plays and touring widely into the late 1990s.

Morton has invited members of the troupe from its Santa Barbara years to attend the conference.