An Ancient Economy

As one of the most experienced archaeologists studying California’s Native Americans, Lynn Gamble knew the Chumash Indians had been using shell beads as money for at least 800 years.

But an exhaustive review of some of the shell bead record led the UC Santa Barbara professor emerita of anthropology to an astonishing conclusion: The hunter-gatherers centered on the Southcentral Coast of Santa Barbara were using highly worked shells as currency as long as 2,000 years ago.

“If the Chumash were using beads as money 2,000 years ago,” Gamble said, “this changes our thinking of hunter-gatherers and sociopolitical and economic complexity. This may be the first example of the use of money anywhere in the Americas at this time.”

Although Gamble has been studying California’s indigenous people since the late 1970s, the inspiration for her research on shell bead money came from far afield: the University of Tübingen in Germany. At a symposium there some years ago, most of the presenters discussed coins and other non-shell forms of money. Some, she said, were surprised by the assumptions of California archaeologists about what constituted money.

Intrigued, she reviewed the definitions and identifications of money in California and questioned some of the long-held beliefs. Her research led to “The origin and use of shell bead money in California” in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

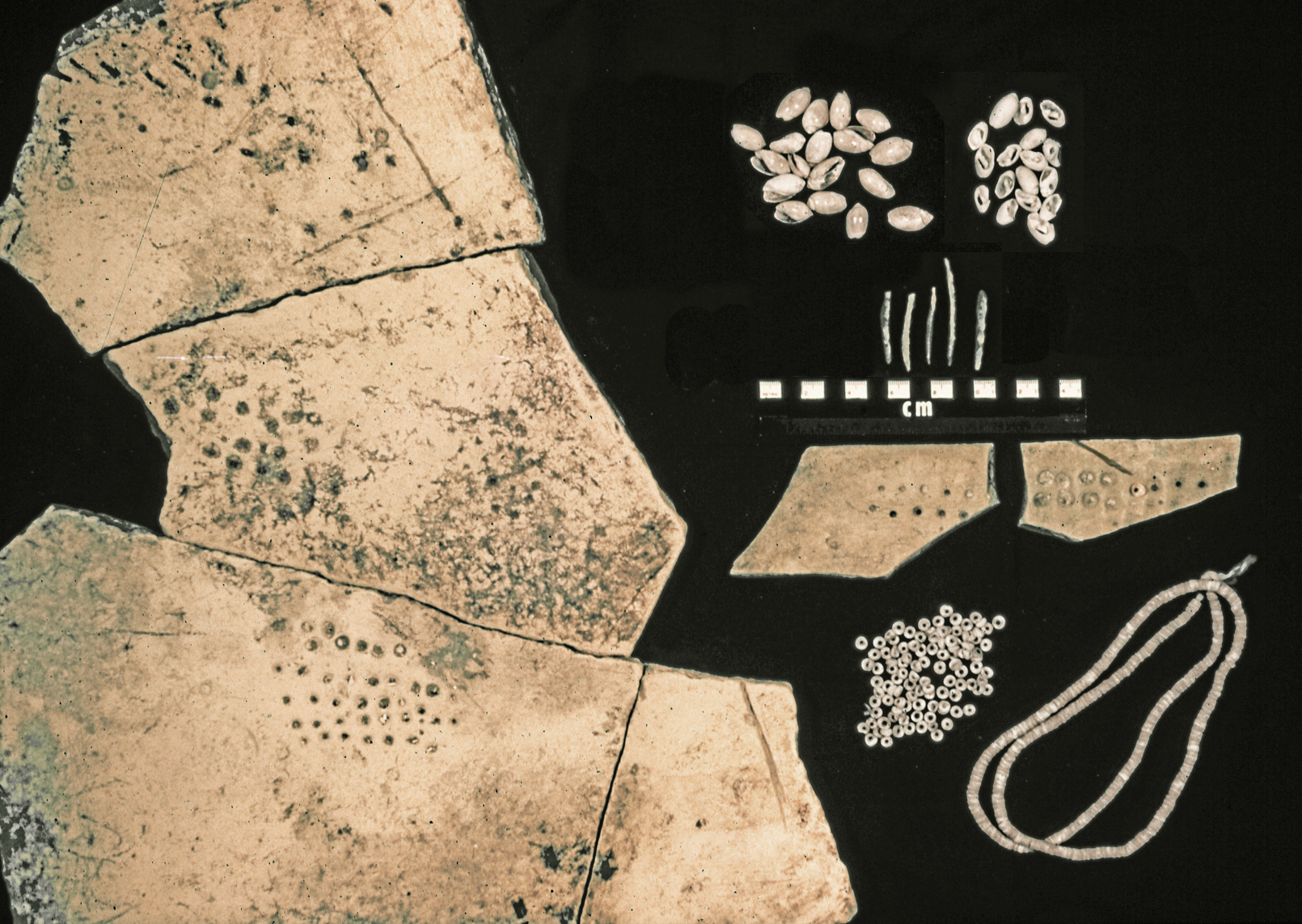

Gamble argues that archaeologists should use four criteria in assessing whether beads were used for currency versus adornment: Shell beads used as currency should be more labor-intensive than those for decorative purposes; highly standardized beads are likely currency; bigger, eye-catching beads were more likely used as decoration; and currency beads are widely distributed.

“I then compared the shell beads that had been accepted as a money bead for over 40 years by California archaeologists to another type that was widely distributed,” she said. “For example, tens of thousands were found with just one individual up in the San Francisco Bay Area. This bead type, known as a saucer bead, was produced south of Point Conception and probably on the northern [Santa Barbara] Channel Islands, according to multiple sources of data, at least most, if not all of them.

“These earlier beads were just as standardized, if not more so, than those that came 1,000 years later,” Gamble continued. “They also were traded throughout California and beyond. Through sleuthing, measurements and comparison of standardizations among the different bead types, it became clear that these were probably money beads and occurred much earlier than we previously thought.”

As Gamble notes, shell beads have been used for over 10,000 years in California, and there is extensive evidence for the production of some of these beads, especially those common in the last 3,000 to 4,000 years, on the northern Channel Islands. The evidence includes shell bead-making tools, such as drills, and massive amounts of shell bits — detritus — that littered the surface of archaeological sites on the islands.

In addition, specialists have noted that the isotopic signature of the shell beads found in the San Francisco Bay Area indicate that the shells are from south of Point Conception.

“We know that right around early European contact,” Gamble said, “the California Indians were trading for many types of goods, including perishable foods. The use of shell beads no doubt greatly facilitated this wide network of exchange.”

Gamble’s research not only resets the origins of money in the Americas, it calls into question what constitutes “sophisticated” societies in prehistory. Because the Chumash were non-agriculturists — hunter-gatherers — it was long held that they wouldn’t need money, even though early Spanish colonizers marveled at extensive Chumash trading networks and commerce.

Recent research on money in Europe during the Bronze Age suggests it was used there some 3,500 years ago. For Gamble, that and the Chumash example are significant because they challenge a persistent perspective among economists and some archaeologists that so-called “primitive” societies could not have had “commercial” economies.

“Both the terms ‘complex’ and ‘primitive’ are highly charged, but it is difficult to address this subject without avoiding those terms,” she said. “In the case of both the Chumash and the Bronze Age example, standardization is a key in terms of identifying money. My article on the origin of money in California is not only pushing the date for the use of money back 1,000 years in California, and possibly the Americas, it provides evidence that money was used by non-state level societies, commonly identified as ‘civilizations.’ ”