The Ripple Effects of a Cinematic Wave

“Catching a wave” is the popular pastime of surf enthusiasts. But the phrase is a bit of a misnomer, in that waves aren’t singular. One follows another and another, together creating the thrilling conditions surfers crave.

That’s also true of metaphorical waves. Take the cinematic explosion popularly known as the French New Wave. The term usually refers to a few years in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and a handful of filmmakers such as Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard. But its roots can be traced to the immediate post-World War II period, and its influence can be felt as recently as 2011.

At UC Santa Barbara, those ripple effects will be explored in “New Waves,” the Carsey-Wolf Center’s spring film series, which runs April 18 through May 23 at the Pollock Theater. It starts with a masterpiece of Italian neo-realism, “Rome Open City,” and includes films from Cuba, China, Iran and, of course, France.

“We didn’t want to do a strictly French New Wave series,” said Patrice Petro, the Dick Wolf Director of the Carsey-Wolf Center and a professor of film and media studies. “We wanted to show its lasting legacy in multiple countries.”

The New Wave represented an opening up of film’s possibilities, in terms of both style and substance. In Petro’s words, its filmmakers created “a new kind of cinematic language” in which filmmakers were “trying to tell different kinds of stories in different kinds of ways.”

“The concept of New Wave is disruptive,” added Cristina Venegas, an associate professor of film and media studies, who curated the series along with Petro and Anna Brusutti, a lecturer in the department. “In France, Truffaut wrote a film manifesto that looked derisively at ‘the cinema of quality,’ a term which was associated with a more conservative type of filmmaking.

“At the same time, you had new technological forms, like lighter cameras, that allowed cinematographers to do things differently,” she continued. “Together, this made possible a multiplicity of styles.”

Filmmaker Godard famously remarked that all roads lead to “Rome Open City,” which makes that landmark film a logical starting point for the Carsey-Wolf series. Roberto Rossellini’s 1945 drama, which tells a fictional story of resistance fighters in fascist Rome during World War II, was shot on the same streets where similar scenes played out in real life only a year or two earlier. That sense of verisimilitude, along with strong pacing and several superb performances, gives it enormous emotional power.

“It seemed to be ripped from the headlines, and the images seemed to be documentary footage,” Petro said. “It opened up a new way of filmmaking which was a stark departure from classical narrative conventions. The main character (played by Anna Magnani) is killed off halfway through the film! People think that began with ‘Psycho,’ but it was actually ‘Open City.’”

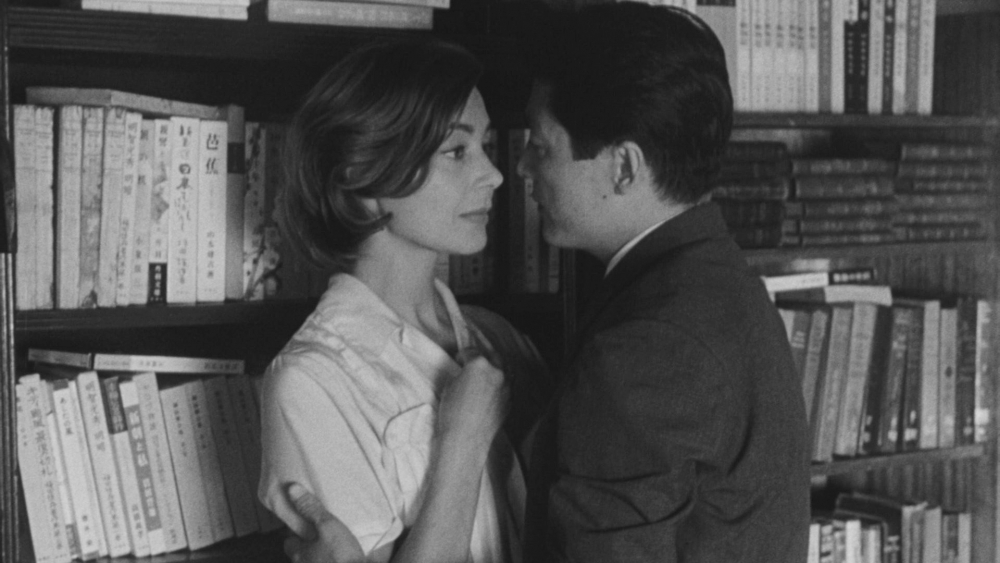

The series continues April 25 with a masterpiece of the French New Wave, Alain Resnais’ “Hiroshima, Mon Amour.” In the 1959 film, a French actress (Emmanuelle Riva) goes to the Japanese city to make a film, has an affair with a local man and relives some of her own experiences in the German occupation of France.

“It’s a really beautiful film — a somber, sensual look at the aftermath of a catastrophe,” Venegas commented.

The series resumes May 18 with the 1989 Chinese film “Red Sorghum,” a tale of rural mid-century China that Roger Ebert praised for “the almost fairy-tale qualities of its images, and the sudden shockingness of its violence.” The post-screening discussion for this film will be moderated by UC Santa Barbara Ph.D. candidate Wesley Jacks, an expert on Chinese cinema.

The 1968 Cuban film “Memories of Underdevelopment” will screen May 21. It is the tale of a wealthy Havana resident who decides to stay put after the revolution rather than following his wife to the U.S. Petro calls it “a meditative look at post-revolutionary Cuba. He’s unmoored in this new world.”

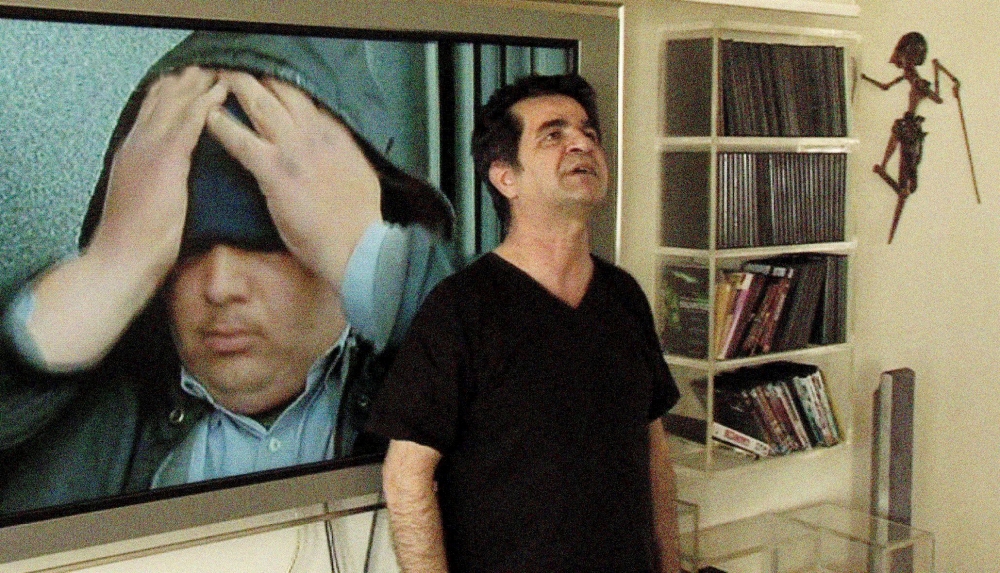

The series concludes May 23 with “This is Not a Film,” a 2011 work which Iranian director Jafar Panahi shot in his own apartment while under house arrest. “He was banned from making films, so he had to find legal loopholes to get around that,” said Petro. “He shot in on a camcorder and an iPhone. It’s really an extraordinary film.”

While each of the films is political, none has a preachy or didactic tone. Rather, they are about people living in fraught, dangerous, and highly uncertain times, trying to navigate a murky ethical landscape. “The questions about morality that these films raise are very profound,” Venegas said. “They are set in moments of moral transition.”

Each screening will be followed by a 35-minute discussion with one or two guests, and then a question-and-answer session with the audience. “We are thrilled to have a chance to share these groundbreaking films with the campus community,” Petro said. “I’m committed to meeting people where they are, and taking them places they’ve never been.”

All films screen at 7 p.m. except “Red Sorghum,” which begins at 2 p.m. Admission is free, but reservations are recommended. Questions may be directed to (805) 893-5903, or info@carseywolf.ucsb.edu.