Set to Music

To some degree, music is enigmatic in nature — a powerful shared cultural experience, yet experienced so differently by each of us. As goes a line from “Score: A Film Music Documentary,” music is “the one thing that we all understand that we don’t understand.”

Researchers at UC Santa Barbara are trying to change that.

Driven to explore and shed scholarly light on music, UCSB’s Center for the Interdisciplinary Study of Music (CISM) aims “to connect people across campus working on music to create points of conversation and dialogue.” That’s according to director David Novak, an ethnomusicologist and associate professor of music at UCSB.

“Music is especially ripe for interdisciplinary work,” said Novak, noting that most university music departments tend to focus on western classical music. “It’s really restrictive to stick to the methodology of one department, in the same way sociology isn’t the only place to study society.”

To promote such work, CISM sponsors an ongoing array of events, including films (it recently screened the aforementioned “Score”), concerts, workshops and symposia. For its ongoing series CISM in the Archive, a collaboration with UCSB Library, the center each year invites a music scholar to explore the historical sound archives in UCSB Library’s Special Research Collections, then present a public lecture.

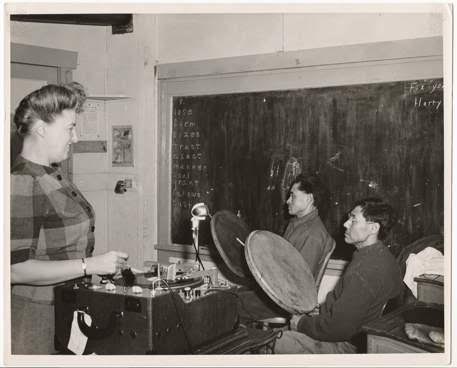

This year Aaron Fox, associate professor of music and director of the Center for Ethnomusicology at Columbia University, gave the free talk, “Decolonizing the Ethnomusicological Archive,” discussing field recordings collected by ethnomusicologist Laura Boulton with Iñupiat people in and around Barrow, Alaska. Fox and his collaborator Chie Sakakibara returned those recordings to the Iñupiat community in a process called “repatriation.” In the talk, Novak said, Fox argued that the project “attempts to address and partly repair some of the colonial violence that allowed researchers like Boulton to use their institutional power to collect music in the first place.”

Much interdisciplinary work on music has developed in the humanities and social sciences, but Novak whose research explores the globalization of music and how it changes culture, sees potential for collaborations with natural sciences as well.

“For example, marine biologists are recording the sounds of sea animals and plants and exploring what they tell us about ocean life,” he said.

Other academics whose interests might intersect with music studies range from anthropologists, economists and historians to engineers, mathematicians and philosophers. CISM’s board, featuring faculty from film and media studies, sociology, Black studies, Chicano/a studies and history, as well as musicology, further reflects the diversity of disciplines engaged with such research.

In the fall, CISM is planning an event with Alex Chávez, author of “Sounds of Crossing,” a book that explores the aural politics of Mexican migration through the sounds of huapango arribeño, a musical genre that began in north central Mexico.

CISM’s interdisciplinary focus also extends to the emerging discipline of sound studies.

“What happens when consider sound as a new research subject?” Novak said. “For example, how does the technology of a stethoscope produce modes of listening to the body? Does the way people listen through ear buds differ from how they listen on a speaker system, or in a car, or in a disco? What happened to our perceptions of sound when the phonograph was invented, and suddenly you could hear something twice exactly the same way?”

The study of sound “raises questions that cut across geography, time and place, and is truly interdisciplinary,” Novak said. “It’s not oppositional to music — it just expands the ways we think about music.”