‘Right at the Equator’

Computer keys strung together. Oil drums. A sculpture of an African Samurai fashioned from rubber tire tubing. This is contemporary African art.

Western notions of African art — and by extension, views of Africa itself — are stuck in the wrong moment, believes Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie, a UC Santa Barbara professor of art history who specializes in the visual cultures of global Africa. As co-curator (along with Valerie Kabov) of “Right at the Equator,” an exhibition of African art by 22 artists on display at the Depart Foundation in Malibu, he hopes to bring us out of our visual time warp.

When people from Southern California think about African art, Ogbechie said, they are probably most familiar with classical or traditional African art shown at places like the Fowler Museum at UCLA or the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“Those are great collections, and I work with those institutions extensively, but they are showing artworks that represent cultural production in the middle of the 20th century,” Ogbechie said during a tour of the exhibition, “and people make the assumption that’s what artists are still doing in the present. This exhibit is trying to change that viewpoint.”

The works in “Right at the Equator” represent contemporary Africa in both a social and aesthetic sense, recognizing the artists in a political and geographical setting, but also affirming them as groundbreaking visual creators on their own terms.

With three works featured in the exhibition, South African artist Nicola Roos, for example, creates intricate life-size figures made from discarded inner tire tubing. “No Man’s Land VI,” features an African man dressed in full Samurai garb. Roos based the piece, Ogbechie explained, on the interesting historical fact of an African samurai who was an attendant to the Samurai warlord Oda Nobunaga in the 16th century.

“She’s playing with this idea of identity and cultural authenticity,” Ogbechie said. “Every single element, including the weapons, is authentically correct. But the idea of an African who is a Samurai is incongruous. Japan was a closed society for almost 300 years. By placing this African person inside a canonical icon of Japanese identity, she is challenging the idea of cultural purity.”

Also on display is Algerian artist Lydia Ourahmane’s installation of oil barrels — real containers used to export oil from her native country. According to Ogbechie, the installation explores the narrative of the politics of global trade. “Something that is vital to the modern world seems to always be produced in black and brown environments where the citizens don’t actually get the benefit of that raw material,” he said.

But beyond “the politics of these works,” Obgechie added, he hopes viewers will “think about these people as artists, and how the politics is subsumed within an aesthetic that is extraordinarily amazing.”

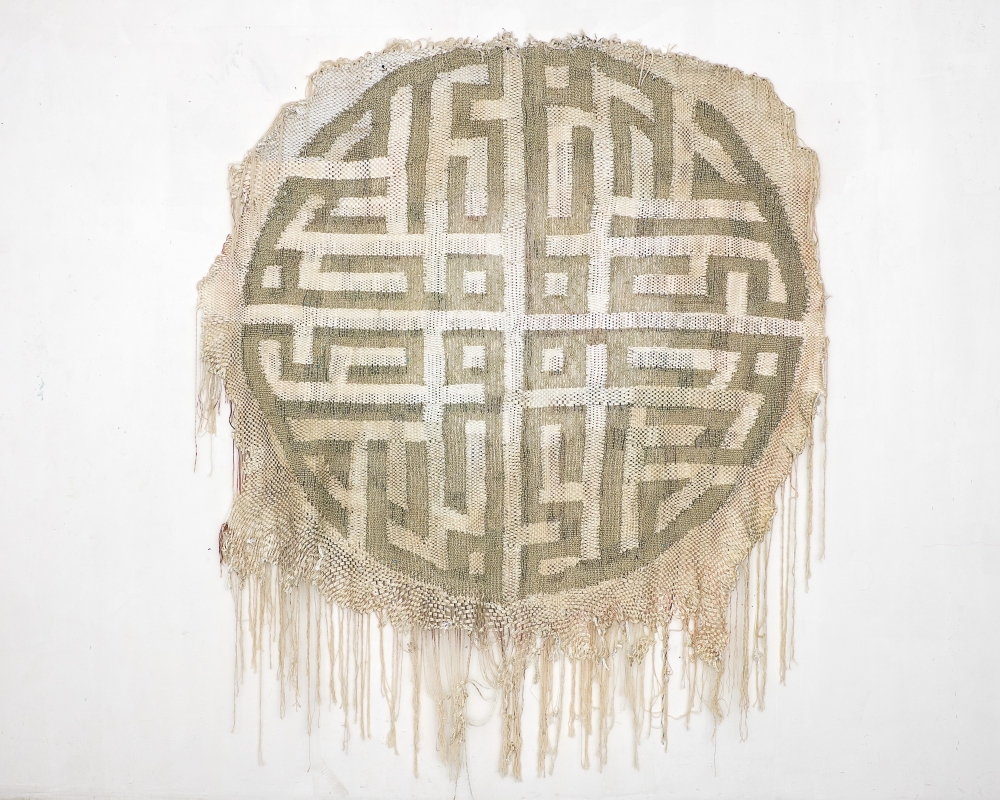

For example, Zimbabwe artist Moffat Takadiwa’s “Hello- Hello- paRadio” is a large wall hanging made out of strung-together computer keyboard buttons. Takadiwa subverts the colonial language of English represented by the keyboard letters, and also addresses Africa’s role as a “dumping ground for obsolete western technology,” Ogbechie said. He also refers to the piece’s “craftsman sensibility. Think about the work it takes: You have to bore four holes in each of these computer keys in order to attach them to the other keys.”

Most of the works in the exhibition, Ogbechie said, “are involved in ‘making’ in a really fundamental sense. It goes back to the actual Greek work for art, ‘techne’: that idea of investing significant effort into the production of complex objects.”

Ogbechie studied art himself, graduating with a degree in painting from the University of Nigeria, then earning a Ph.D. in art history from Northwestern University. He is also the founder and editor of “Critical Interventions: Journal of African Art History and Visual Culture,” and director of Aachron Knowledge Systems, which “educates clients about the equity value of different forms of global African arts.”

“I gave up on the production part of art to focus on curatorial projects and historical analysis,” he said. “We need people in that area. The West Coast is lagging far behind in the representation of contemporary African art.”

To that end, Ogbechie said, he hopes to plan a day trip for his students to visit the Malibu exhibition. “It’s important that these kinds of exhibitions take place so that when I am teaching my students, I can point to things happening closer to home,” he said. “I want them to think of globalization not in terms of something that applies to Africa by colonization, but something that is emerging from Africa to the wider world.”

“Right at the Equator” is on display through Feb. 28 at the Depart Foundation, 3822 Cross Creek Road, Suite 3844, Malibu. Gallery hours are noon to 6 p.m. Tuesdays through Sundays.