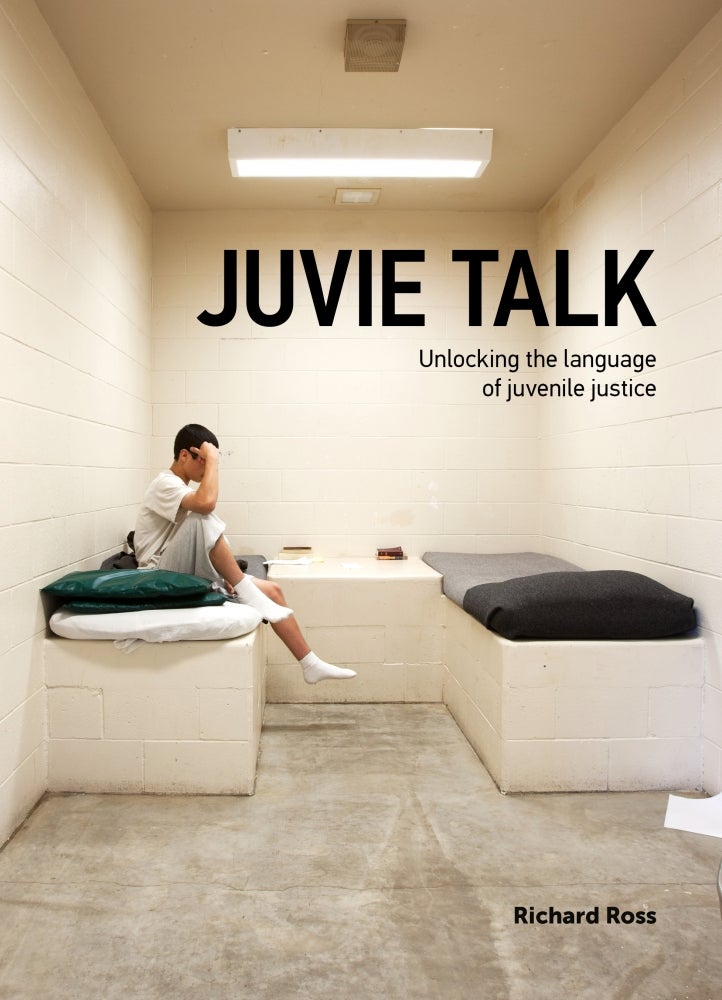

Juvie Talk

With his legs outstretched, T. barely fits the diameter of the small animal pen that surrounds him. Clad in an orange jumpsuit, he sits in the dirt, cuddling a rabbit to his chest. He gazes down at the small animal, gently stroking its ear with his thumb and forefinger.

At 16, T. is on his second go-around in juvenile detention, locked up for running away, breaking and entering and burglary. With no one looking after him, T. found ways to fend for himself.

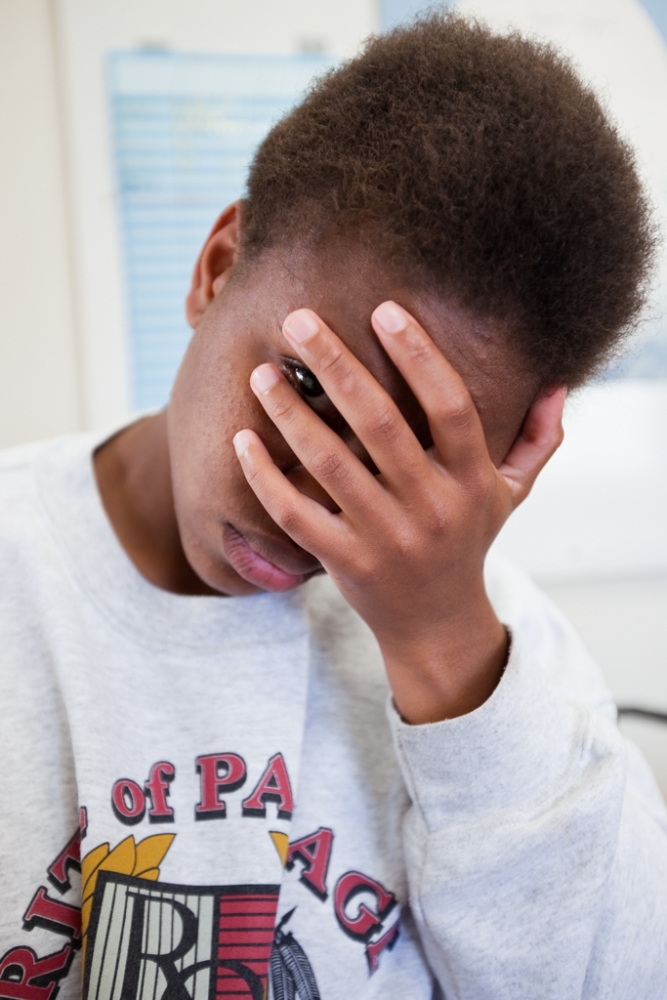

E.E. was 12 years old when she landed in the system for the first time. Now 13, she has been in juvenile detention five times. When not detained, she lives with her mother and sister, and hasn’t seen her father since she was two.

In Their Own Words

T. and E.E. are among the 111 teenagers and adolescents featured in Richard Ross’s new book, “Juvie Talk: Unlocking the Language of Juvenile Justice” (The Image of Justice, 2017). Ross, a professor of art at UC Santa Barbara, interviewed the incarcerated youth in a variety of juvenile placement facilities — detention centers, correctional facilities and boot camps to hear, in their own words and vernacular, what is true about their lives.

“The ultimate purpose is to build empathy for these kids among the junior high and high school peers their own age,” said Ross. “So these kids can add their own stories and say, ‘Well, this kid was abused; I was abused, too.’ And it becomes very interactive.”

Real Life Make-Believe

And therein lies the purpose of the companion Juvie Talk web site. Established in conjunction with the book, it helps visitors turn their experience into art. Users — primarily teachers and students, though the site is available to anyone — input specifics about the number of actors, key topics they want to cover and the performance length, and the site’s Play Builder function will create a custom script they can use to develop their own Juvie Talk performances. Ross has made the process simple, fast and free to move these stories — these lives — into the classroom where the real stakeholders exist.

Exploring the language of the teens and adolescents featured in the book, teachers and students can discover where their peers’ experiences match their own.

“I wanted to create a curricular element that’s organic, variable in length and that kids can put together and use it as a vehicle for juvenile justice and human rights.

“Juvie Talk” the book is the third in Ross’s award-winning “In Justice” series. “Girls In Justice,” which came out in 2015, explores the conditions and contexts of girls remanded to detention centers. It was preceded by “Juvenile In Justice,” which documents the placement and treatment of juveniles in facilities that are meant to assist, confine and/or punish them.

Leave Your Shoes at the Door

The work requires a blend of artistic vision, sensitivity and a high degree of emotional intelligence, all of which Ross has honed over the years he has spent interviewing and documenting more than 1,000 of these young people. Ross’s work has taken him to over 400 sites and 35 states.

His interview process is simple and respectful. “I’ll knock on the door and ask if I can come in,” he said. “This is unusual for the kids.” Once invited in, he removes his shoes and leaves them at the door because, as he said, often these kids have had their shoes taken away. Then he sits on the floor, allowing the kids to be in a position of physical superiority.

And then he listens.

“I ask them to tell me what their life was like before they got here,” Ross said. “I usually start off with ‘Who visits you?’ and it’s like, a mother. ‘Does your dad visit you?’ and the response is ‘I don’t know my dad.’”

Most important, he noted, is making clear to the kids they don’t have to say anything they’d rather keep to themselves. “In fact, I force them to say no to me. I tell them they have to say the words ‘No, I don’t want to talk about that.’ And after some encouragement, they do. And I remind them they can say that at any time. I tell them I’ll never hurt them; nothing bad is going to come of the conversation; and though I can’t really help, I’m here to listen.”

A Privilege and a Gift

Given the sheer number of detention centers Ross has visited, as well as the number of residents he has interviewed, Ross has a rare perspective on the lives and histories of the teens and adolescents he has photographed. He also has become a conduit between them and the world, giving voice to kids who otherwise have no way to speak up. And the majority of those he has queried have been willing to talk. “They’re teenagers and they’re bored, and some of them have been locked up, some have been put in isolation or administrative segregation,” he said. “And all the girls have been raped. All of them.”

Ross pauses. “So I have to consider [being with these kids] an incredibly responsible and rich time. It’s an amazing privilege and a gift,” he said. “I don’t want to blow it.”

The roots of Ross’s current series extend to his father, a police officer in New York City. “It started with my dad being a cop,” he said. “You go to the way-back machine and realize you’re dealing with authority and police officers and precincts in New York City in the 1940s and 50s. Somehow I evolved into doing political work.” Then Ross’s work began to encompass beautiful photographs that were exhibited in prestigious museums and galleries. “But my heart was always in politics and social causes.”

No Turning Back

His first foray into photographic social consciousness was “Architecture of Authority” (Aperture Press, 2007) which presents unsettling images of architectural spaces that exert power over the individuals within them. Among those spaces are churches, mosques, civic spaces, the Iraqi National Assembly hall, an interrogation room at Guantánamo, segregation cells at Abu Ghraib and a capital punishment death chamber.

“By chance I ended up at the El Paso Juvenile Detention Center, which looked a lot like Guantánamo, where I photographed,” Ross recalled. I thought, ‘How do you have a juvenile detention center that’s similar to Guantánamo in its architecture?’

“Then I started talking to the kids,” he continued, “and once that happened there was no turning back. And before that work was published, and before the ‘Juvenile In Justice’ book, I was able to gain access because people didn’t realize what I was doing.”

Sufficiently Dangerous

However, over time, Ross’s cloak of anonymity has begun to wear thin.

“Leon Gollub, a great painter, was once asked whether the arts are censored in America. His response was, ‘No, we’re not sufficiently dangerous,’” Ross said. “And I feel like in my small world, my small category, I am sufficiently dangerous. Now most administrators understand what these images are, and many don’t want me in their facilities because they won’t be shown in a good light.”

Still, there are some who see great value in Ross’s work. “Like those in Houston, where the director said ‘I know what you do and I want you to document it,’” he recalled. “‘I’ll drive you around and I want you to photograph the good, the bad and the ugly so we can do something to change the system to have a better outcome for the kids.’”

Nobody Teaches; Everybody Learns

And that takes Ross back to the theatrical component of “Juvie Talk.” “You can’t have a tremendous impact, but not to try to do something is morally reprehensible,” he said. “Hence the play. You try to get the kids to be in the other kids’ shoes. And you offer a little stage direction, like stand up in front of the class and take off your shoes. See what that feels like.”

It’s empathy Ross is dealing in.

“What’s the bigger takeaway for the kids doing this?” he asked. “Nobody teaches; they all learn. If you create an environment where they can learn, they all get it. They learn from each other. These are the voices of each other talking. And they can inject their own voices — interrupt, stop whoever is speaking — and say, ‘I knew a kid who smelled bad.’ And then create a dialogue. ‘Why did he smell bad?’ ‘Because he didn’t have the means to wash his clothes.’ ‘I knew a kid like that.’ And they understand.”

A Collaborative Effort and Free of Charge

Ross produced the material with support from the MacArthur Foundation and in collaboration with director Peter Sellars. And he has made it available to any educator who wants to use it. “We’re literally giving it away,” he said. “But money isn’t the reward for this. My goal is to have someone email me and say, ‘I saw your work produced at a middle school in Kansas and it had a huge impact.’ I hope to see it pick up its own direction and momentum. The aim is to have these stories heard and to have the incarcerated kids realize there are people, their own peers, who have not forgotten them.”