Unequality and Normalization

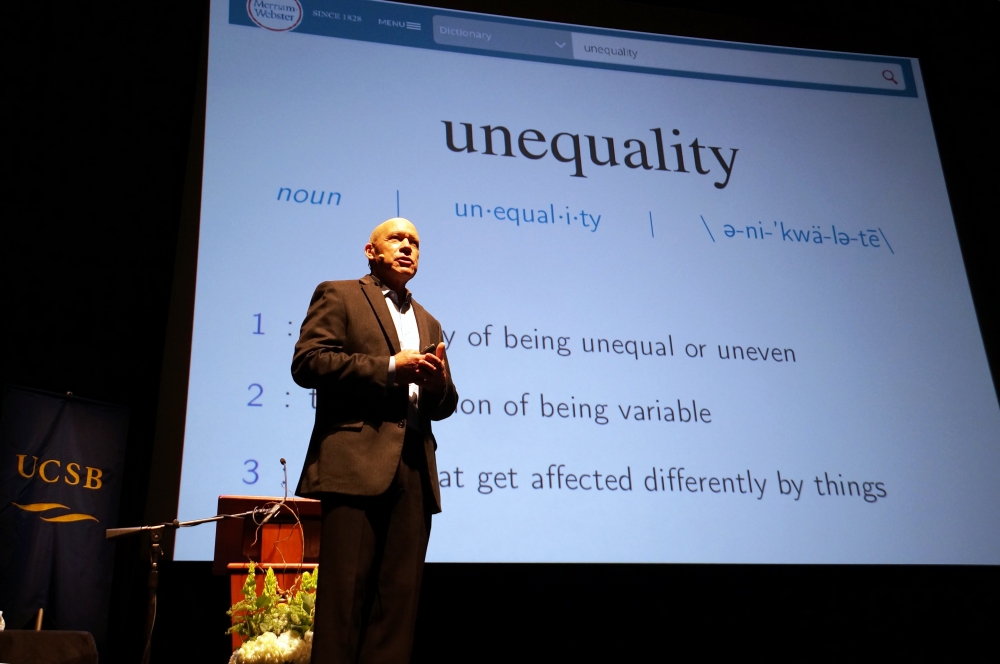

The good news: In Santa Barbara, the housing market has stabilized, employment is strong and wages are up. The not-so-good news: You might not be noticing this economic bounce back — at least not yet — because of this thing UC Santa Barbara economist Peter Rupert calls “unequality.”

“It’s everywhere; not everything moves together,” Rupert said during the annual UCSB Economic Forecast Project Summit that took place at the Granada Theatre in Santa Barbara Thursday, May 5. Despite numbers pointing to upward trends, economic indicators such as wage growth and employment and unemployment rates, the diversity of local economic factors across the nation, in California and even in Santa Barbara means some areas feel the general improvement more strongly than do others.

The Wealthy Are Back on Track, the Lowest 25 Percent — Not So Much

“There is wage growth, but it’s not equally distributed,” said Rupert, executive director of the forecast and chair of UCSB’s economics department. Graphs that track earnings from 2003, through the Great Recession, to the present, show the wealthiest 10 percent of the population having already surpassed their 2003 earnings by 8 percent. For the rest of the population, however, the recovery is slower, with the lowest 25 percent of wage earners still below their 2003-level earnings.

Home Values Are Rising, But Unevenly

Across California, home values by counties, tracked from 1996, clearly show this relatively recent “unequality” trend. They rose in unison until the recession hit, and even fell in unison during the first years of the downturn. But they followed independent trajectories as the economy began to recover. For example, San Francisco’s home values are higher now than they were at the 2006 peak; other areas, including Los Angeles, San Diego, Santa Barbara, Sacramento and Riverside, are still below their pre-recession values.

The trend plays out even across the cities within Santa Barbara County. Home values in Montecito have surpassed their 2006 peak and those in the city of Santa Barbara are approaching their pre-recession values. Carpinteria and Goleta are catching up, but in

Buellton, Santa Maria, Lompoc and Guadalupe the recovery is more sluggish. “We can go even farther in,” said Rupert, pointing out discrepancies in home values even among neighborhoods in downtown Santa Barbara, the Mesa and the Riviera.

Rupert’s breakdown of the local and regional economies — which also touched on topics such as California’s new minimum wage hike and the growth (or shrinking) of different industry sectors — was among several summit presentations. The event also featured guest speakers James Bullard, president and chief executive officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; market and investment experts Rob Arnott, founder and chairman of the investment strategy firm Research Affiliates; and Chris Ludeman, global president of capital markets for CBRE Group.

An Expectation Gap

In wide-ranging presentations and discussions, the speakers examined a variety of issues, from the closely watched federal interest rate, to inflation, to the difficulty in predicting the future.

“What I’m talking about here is an expectations gap,” said Arnott. “People want to believe their investments will be a source of substantial returns in the years ahead.” Short-term predictions, he noted, are “a little bit of a silly game.” Long-term financial vision might require a little more work and endurance, but in the end could provide more fruitful and reliable returns.

Still, investors and economy wonks everywhere remain vigilant and even skittish as they monitor the Fed and the regular meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to see whether the federal policy rate will take another step upward. After hovering near zero since the beginning of the recession, the rate was raised last December. As the instrument used by the Federal Reserve to control the flow of cash from one bank to another, the federal policy rate affects financial decisions on virtually every level of the economy.

The Fed and Interest Rates

At the meeting in late April, the FOMC chose to maintain the quarter-point to half-point target range increase it implemented in December. But in its effort to normalize the policy rate, the committee could pursue another increase in June.

Citing relatively strong U.S. labor markets, U.S. inflation close to 2 percent and waning international headwinds, Bullard noted the committee’s plan to normalize the policy rate over the next several years. “The FOMC has laid out, via the Summary of Economic Projections, a data-dependent ‘slow normalization,’ whereby the policy rate would gradually rise over the next several years provided the economy evolves as expected,” he said.

Many factors will have to be monitored regularly along the way, including jobs, gross domestic product and even global developments, Bullard added.

In contrast, the market scenario for the future was more conservative, allowing for a much slower and smaller increase as factors such as recent devaluation of Chinese currency and even the Fed’s apparent intentions to raise the policy rate caused concern among market participants.

Slower is better, according to Ludeman, who advocated for clear signaling from the Fed on its intentions regarding the policy rate. “We believe that as long as the Fed continues to stay behind the curve, as opposed to leading the curve, we will have positive outcomes for business,” he said.