Studying the Outliers

Medical research has yet to discover an Alzheimer’s treatment that effectively slows the disease’s progression, but neuroscientists at UC Santa Barbara may have uncovered a mechanism by which onset can be delayed by as much as 10 years.

That mechanism is a gene variant — an allele — found in a part of the genome that controls inflammation. The variant appears to prevent levels of the protein eotaxin from increasing with age, which it usually does hand in hand with inflammation. The findings appear in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

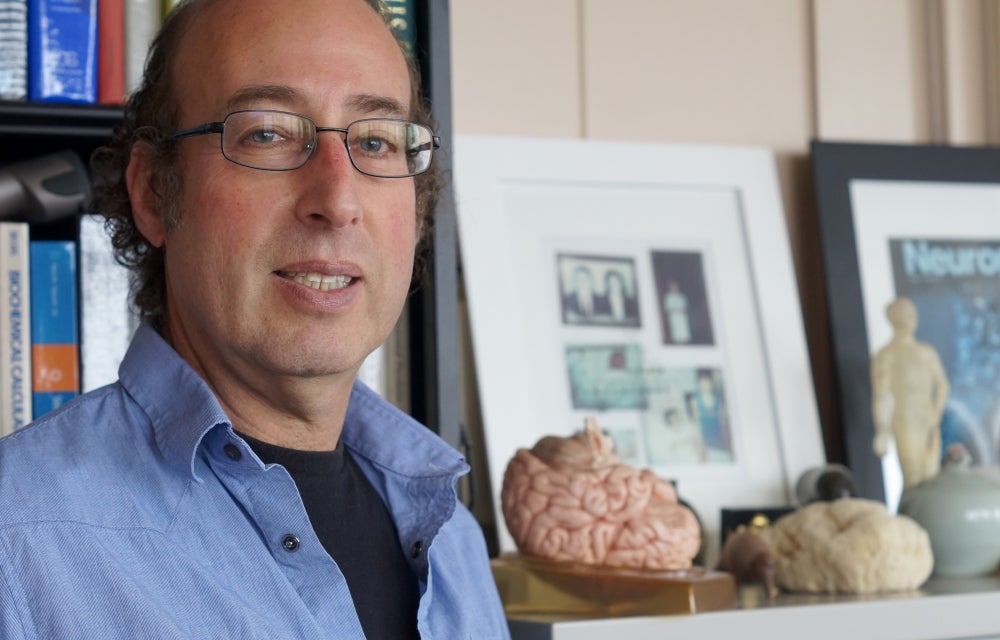

Lead author Matthew Lalli, who earned his Ph.D. working in the Kosik Research Group, sequenced the genomes of more than 100 members of a Colombian family affected with early-onset Alzheimer’s. These individuals have a rare gene mutation that leads to full-blown disease around age 49. However, in a few outliers, the disease manifests up to a decade later.

“We wanted to study those who got the disease later to see if they had a protective modifier gene,” said co-author Kenneth S. Kosik, co-director of the Neuroscience Research Institute and a professor in the Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology. “We know they have the mutation. Why are they getting it so much later when the mutation so powerfully determines the early age at onset in most of the family members? We hypothesized the existence of gene variant actually pushes the disease onset as much as 10 years later.”

Lalli used a statistical genetics approach to determine whether these outliers possess any protective gene variants, and he found a cluster of them. “We know that age is the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s beyond genetics,” said Lalli, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at Washington University in St. Louis. “The variant that we found is age-related, so it might explain the actual mechanism of how an increase in age increases the risk of Alzheimer’s — through a rise in eotaxin.”

To replicate the findings, the researchers collaborated with UC San Francisco to study 150 individuals affected with Alzheimer’s or dementia. UCSF investigators measured levels of eotaxin in the participants’ blood and collected DNA samples to confirm who carried the gene variant identified in the Colombian population.

The results showed that people in the UCSF study with the same variant had eotaxin levels that did not rise with age. They also experienced a modest but definite delay in the onset of Alzheimer’s. “If you have that variant, maybe one way to delay or reduce your risk for Alzheimer’s is by genetically holding in check the normal increase in eotaxin that occurs in most of the population,” Kosik explained.

“Although the gene mutation in the Colombian population is extremely rare, this variant is not,” he added. “It occurs in about 30 percent of the population, which means it has the potential to protect a lot of people against Alzheimer’s.”

Previous independent work at Stanford University has shown that adding eotaxin to young mice made them functionally older. Stanford is also currently testing whether blood transfusion from young individuals to older ones confers benefits. “The results of this work may provide additional evidence that eotaxin plays a role in the deleterious effects of aging,” said Lalli.

“We have an important preliminary finding,” said Kosik. “If this is a true mechanism of Alzheimer’s progression, then we can modify the level of eotaxin in individuals to treat the disease. But our results must be replicated and proved by other laboratories — and in larger populations.”