The Death of Kings

Producing one of William Shakespeare’s history plays is complicated enough, but eight? And at the same time? Some might call that downright crazy. But not director Irwin Appel, who has taken on the challenge with groundbreaking results.

In “The Death of Kings,” Appel, a professor of theater arts at UC Santa Barbara, has adapted all eight of Shakespeare’s histories into a two-part epic to be performed by UCSB’s Naked Shakes. The first, “I Come But For Mine Own,” melds “Richard II”; “Henry IV, Part I”; “Henry IV, Part 2”; and “Henry V.” The second, “The White Rose and the Red,” brings together “Henry VI,” parts 1, 2 and 3; and “Richard III.”

While “The Death of Kings” will have its world premiere in February, this week Naked Shakes is giving audiences a glimpse of what they can expect to see in full six months from now. On Wednesday and Thursday, Sept. 2 and 3, the actors will present excerpts from each part of “The Death of Kings” at 8 p.m. in UCSB’s Hatlen Theater. The performances are free and open to the public.

“The original plays themselves have a wealth of material,” said Appel, “and what I was attempting to do when I began this project a year ago was to see which characters in particular, which arcs would really shine through if I tried to put them all together. What I found were some very exciting things.”

Appel noted that for the upcoming preview, narration has been added to help fill gaps in the storyline, and because this summer production includes two UCSB Summer Sessions courses, on some occasions more than one actor will play the same role.

Like other Naked Shakes productions, “The Death of Kings” is both scholarly and interdisciplinary in nature. Simon Williams, former chair of the Department of Theater and Dance, is serving as the dramaturg, or the scholar of the production, as Appel described it, and he will include his graduate students in the process.

In addition, Appel has formed academic alliances with faculty members in the English department who teach courses on Shakespeare so their students can benefit from the production. Appel said he hopes to connect with other departments and areas of campus, including the history, Renaissance studies and, perhaps, religious studies departments, as well as the College of Creative Studies. “I also hope we can create academic events surrounding the play that will bring together scholars and practitioners,” he added.

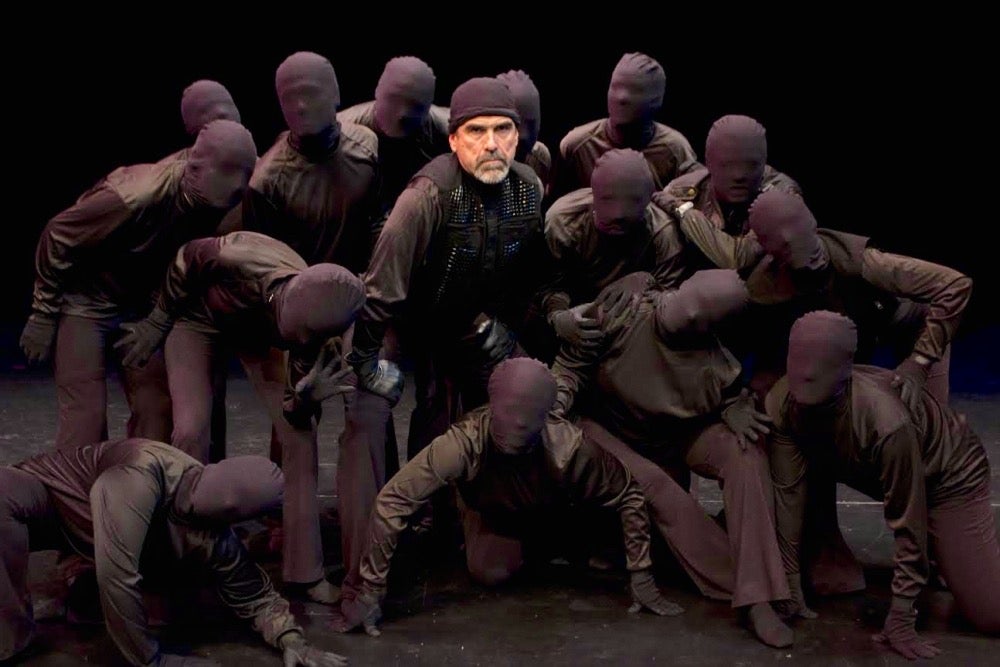

According to Appel, distilling the eight plays into two has been quite a challenge. “I have spent my entire yearlong sabbatical on this, and I have worked on it every single day,” he said. It wasn’t until he’d finished some early drafts that he believed the adaptations would work. “And now we’re doing the summer workshop production, which is a very exciting preview or, as I call it, a trailer production,” he said. “We are creating some theatrical imagery in the Naked Shakes tradition where it’s just the actor and what they can do on a blank stage with a few simple elements.”

Bare-bones theatricality is the hallmark of Naked Shakes, which celebrates its 10th anniversary this year. Each play is presented clearly and directly so the audience inhabits the imaginative world of the play through Shakespeare’s language. The barren physical theater space is very important to the Naked Shakes concept; it takes on the identity of whatever locale or particular poetic language is described, and yet continues to remind the audience they are in a theater. “When Prospero in ‘The Tempest’ describes ‘the great Globe itself,’ he is not only referring to the entire Earth, but also the ‘Globe’ Theater — Shakespeare’s theater,” said Appel. “That duality is what Naked Shakes is all about.”

Previous Naked Shakes productions include “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” “The Tempest,” “A Winter’s Tale,” “Twelfth Night,” “Romeo and Juliet,” “Measure for Measure,” “The Merchant of Venice” and “Macbeth.”

Per Naked Shakes philosophy, the job description of an actor is to step into the shoes of another individual, so roles are not necessarily cast based on the “right” gender, ethnic background, height or weight. “In our production, for example, we have cast a woman in the role of King Richard II,” noted Appel. “We have not changed the gender of Richard’s character; the pronouns are the same: ‘he’ is still a male character and King. We simply found a wonderful actress who exemplifies the essence of this character, so we cast her.”