East Meets West

Were you taking a yoga class a hundred or so years ago, you wouldn’t have brought a mat to class. Nor would you have worn stretchy yoga pants, and it’s highly unlikely you’d have ended a session on your back, eyes closed and concentrating on your breathing. In fact, all the down-dogging, back-bending, tree-standing and warrior posing common today wasn’t even part of the practice in yoga of the early 20th century.

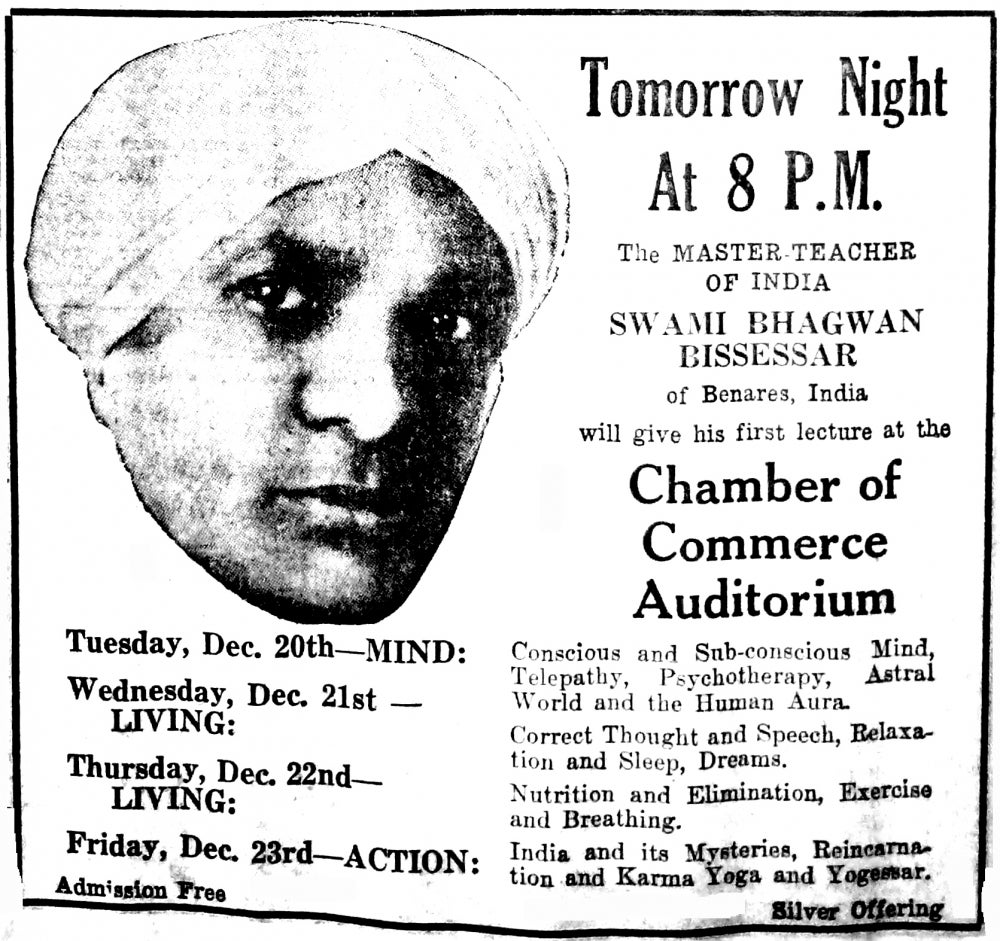

“People sat around in chairs and listened to lectures,” said Philip Deslippe, a UC Santa Barbara religious studies doctoral student who studies the history of yoga in America. The practice that has become so popular in recent decades for the contortions and balancing moves looked very different when it first made the leap from British colonial India to the New World. Deslippe will be giving a lecture, “Early History of Yoga in the United States: 1880-1950,” Tuesday, April 14, at 5 p.m. at the Unitarian Society of Santa Barbara, 1535 Santa Barbara Street.

In fact, early American yoga, as Deslippe calls it, runs against two common assumptions that many people have about yoga.

“The first is that the yoga that everyone’s doing today is ancient, Indian, religious or spiritual, and it comes from a long, unbroken tradition,” he said. “The other assumption is that there really wasn’t a lot of yoga in America until the mid- to late- 1960s, with the growth of the hippie counterculture.”

Through his research, which included a lot of archival digging and interviews with descendants of early 20th century yoga teachers who came to America, Deslippe uncovered a vibrant and colorful yoga culture. It was a culture that was nourished in part by the Orientalism that grew out of the British Raj, and also by the emerging movement in the United States toward spiritual and metaphysical inquiry.

“When you go back a hundred years, you find that people had very different ideas of what yoga is, and what a yogi is,” Deslippe said. Yoga, when it first hit American shores in the last decades of the 19th century, was more mystical and magical, and yogis were imbued with strange and sometimes dark powers.

Santa Barbara in the early 20th century was a hotbed for this new movement toward spiritual and physical wellness and power. The communities of Ojai and Summerland, in fact, emerged from this phenomenon. The yogis, most of whom were well-educated English-speaking members of the British Empire in India, were able to tap into Santa Barbarans’ search for meaning, establishing yoga classes that were quite popular. However, yogis like these were not only business- and marketing-savvy, according to Deslippe, they also became a force for social change.

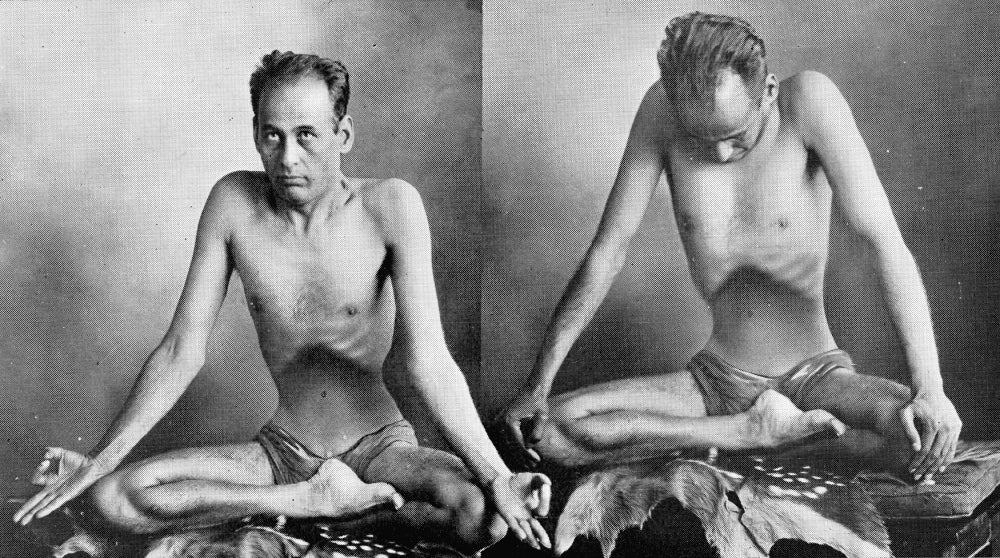

So how did yoga in the United States evolve from discussions in parlors, sitting rooms and auditoriums to the stretching, posing, breathing practice we know today? For that, according to the scholarly work Deslippe has studied in his research, we have the Swedes to thank, as well as the fitness phenomenon of bodybuilding and Western ideas of masculinity.

It wasn’t an instant change, said Deslippe, but a gradual shift. As the popularity of spiritual and mystical thought waned in the country in the mid-20th century, so too did the emphasis on the magical and mystical in yoga, replaced by a more concrete physical expression. Yoga took on influences that guaranteed its own longevity as it promised the same to those who practiced it.

However, if there is one thing that remains constant in the evolution of yoga in the United States, according to Deslippe, it would be the special meaning people still attach to the East — to India in particular — with regard to mysticism and promises of wisdom and enlightenment.

“There’s still a special imprint of a yoga teacher who studied in India, or a teacher who is Indian,” he said. However, he pointed out, it took exposure in America for yoga to become the popular practice that it is throughout the whole world, and even on its home soil.

Deslippe’s lecture, “Early History of Yoga in the United States: 1880-1950,” is a UCSB Affiliates Talk. The event is free of charge to UC Santa Barbara Foundation Trustees, Gold Circle members, Chancellor's Council members and UCSB Affiliates. For non-members, admission is $10. To RSVP, call Kimberly Peden at (805) 893-2877, or email at kimberly.peden@ucsb.edu. Payments (payable to UC Regents) can be sent to the Office of Event Management and Protocol, UC Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-1135, Attn: Kimberly Peden.