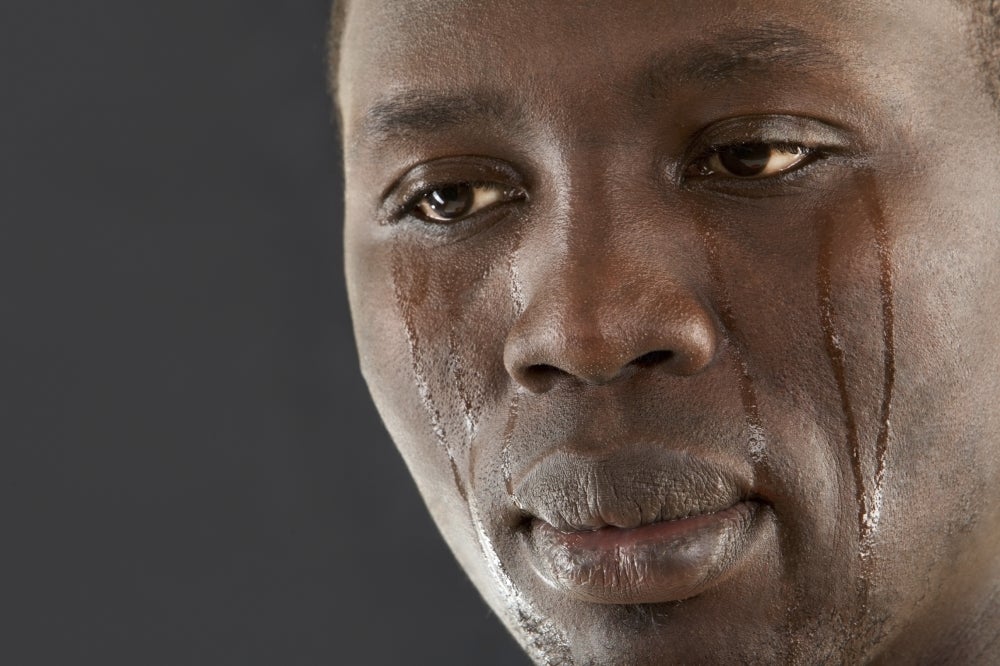

Shame on Us

Emotions are complicated and never more so than in the realm of the scientific, where commonly accepted definitions are lacking.

In a paper published in the journal Qualitative Inquiry, UC Santa Barbara’s Thomas Scheff examines the basic emotions of grief, fear/anxiety, anger, shame and pride as they appear in scientific literature in an attempt to take a first step in defining them. “Emotion terms, especially in English, are wildly ambiguous,” Scheff writes in the paper’s introduction.

An emeritus professor of sociology, Scheff set out to explore why the language of emotion is so vague. “This paper is a first step toward correcting the chaotic nature of the language of emotion,” Scheff said. “Our society treats emotions as a negligible and largely destructive matter, but that’s a total fib. Emotions are like breathing; they only make trouble when they’re obstructed.”

Using grief as an example, he pointed out that in scientific literature other words, such as “distress” and “sadness,” are used to describe grief. The absence of decisive definitions, he noted, are an impediment to creating common meaning.

In order to delineate first steps toward clarity, Scheff discussed what he calls “four forward-looking studies of shame, the least understood emotion.” In this part of his research, Scheff presented a historical picture of how shame has been defined — and used or ignored — over time.

He began with Norbert Elias, an early-20th-century German sociologist famous for his theory of civilizing processes. Elias suggested a way of understanding the social transmission of the taboo on shame. Decades later, English psychologist Michael Billig proposed that repression begins in social practices of avoidance and went on to explore the nature of repression in detail.

American research psychologist and psychoanalyst Helen Lewis, Scheff’s mentor, used a systematic method to locate verbal emotion indicators in transcriptions of psychotherapy sessions. According to Scheff, Lewis’ findings showed that shame/embarrassment was by far the most frequent emotion, occurring more than all the other emotions combined. However, these citations were virtually never mentioned by either the client or the therapist. Lewis called this “unacknowledged shame,” which she explained could be hidden in two different ways.

Overt, undifferentiated shame involves painful feelings hidden behind terms that avoid the word “shame.” This type of shame is marked by pain, confusion and bodily reactions such as blushing, sweating and/or rapid heartbeat. Bypassed shame involves fleeting feelings and is followed by obsessive and rapid thought or speech.

“People are so terribly terrified of shame,” Scheff said. “But if you hurt my feelings by saying that my nose is too big and if I pretend that I’m not hurt, then it’s going to hurt me for a long time. I’ll feel ashamed. But if I say, ‘You hurt my feelings,’ then you say, ‘What do you mean?’ and I tell you my feelings, it’s going to be a fairly minor event. Yet we live in a society that bypasses or misnames emotions, especially shame.”

As far back as the 19th century, psychologists have attempted to establish unambiguous emotional constructs by associating physical sensation with emotion. Building on these concepts, Scheff’s latest research included a chart of emotional models supporting the idea that emotions are bodily preparations for actions that have been delayed.

“Shame is a signal that you feel rejected and not accepted just as you are,” he explained. “Pride is a signal that you feel accepted just as you are. But because emotions are hidden in modern societies, we are like actors on a stage, acting instead of doing what we think we should do.”

Using Ngrams — a word search database created by Google Books and based on more than 5.2 million books published between 1500 and 2008 — Scheff verified a historic decline in the use of shame terms in different languages: American English, British English, French, Spanish and German. He found that decreased usage of what he calls the “s-word” is remarkably similar in three of the five languages: American English, British English and French.

Despite the fact that the use of shame terms appears to be declining, Scheff noted that the topic of shame is present in public discourse now more than ever before. “I’ve written a lot about shame and I’ve noticed that it’s more in vogue,” he said. “And the articles and chapters I’ve written about shame have become more popular in the last year or two as well.” Perhaps with more public discussions about shame, that term as well as other emotions will begin to be more precisely defined.