Better Late Than Never

After a few years of smaller-than-anticipated economic growth, the economists at UC Santa Barbara’s South County Economic Summit projected positive but still very gradual growth both locally and nationally.

“In Santa Barbara, everything seems to be growing pretty well,” said Peter Rupert, executive director of the UCSB Economic Forecast Project, who gave the audience at the Granada Theatre the local view of the economy. Employment rates in the county are better than those elsewhere; the housing market has slowed just a little; and there is strength across most sectors of the local economy, with banking, housing and employment continuing to strengthen over time.

The projections at Thursday morning’s summit were given in the wake of the deepest economic recession in the United States since the Great Depression, from which the country has been slow to recover. As the local economy rebounds, unemployment rates are declining but employment has yet to meet the 2006 pre-recession levels. That can be attributed in part to the large population of students in the county, Rupert said, but also to what he called a “skill mismatch.”

“We’ve had a huge increase in technology — people who are good at technology take advantage of it, other people who are not good at it, maybe they lose their jobs,” he explained.

The information technology sector has experienced the most growth in the last year, but employs only about 2.2 percent of the workers in the county. Government, on the other hand, a sector that employs almost 20 percent of workers in the county, has experienced a dip in growth.

Meanwhile, employment in the manufacturing and goods-producing sectors is trending downward. In contrast, service industry, leisure and hospitality, education and health services and professional and business service sectors have been trending upward, overall. Improvements in employment — albeit slow — are expected to continue. Rupert predicted that most of the local jobs created in the next few years will be below the median salary of $38,000 annually.

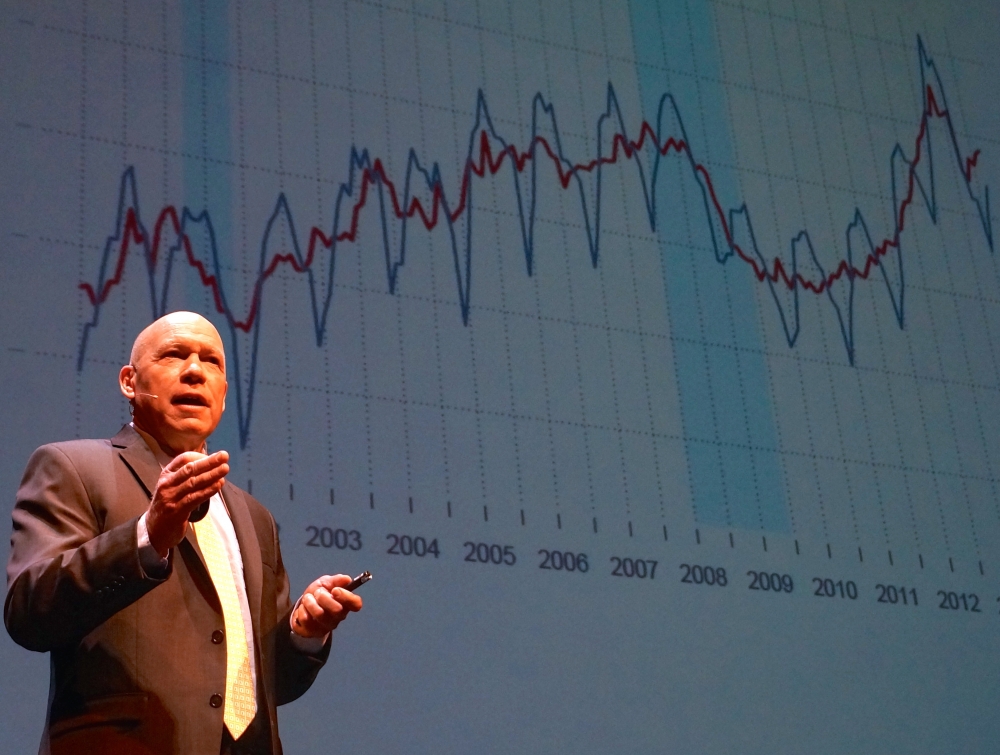

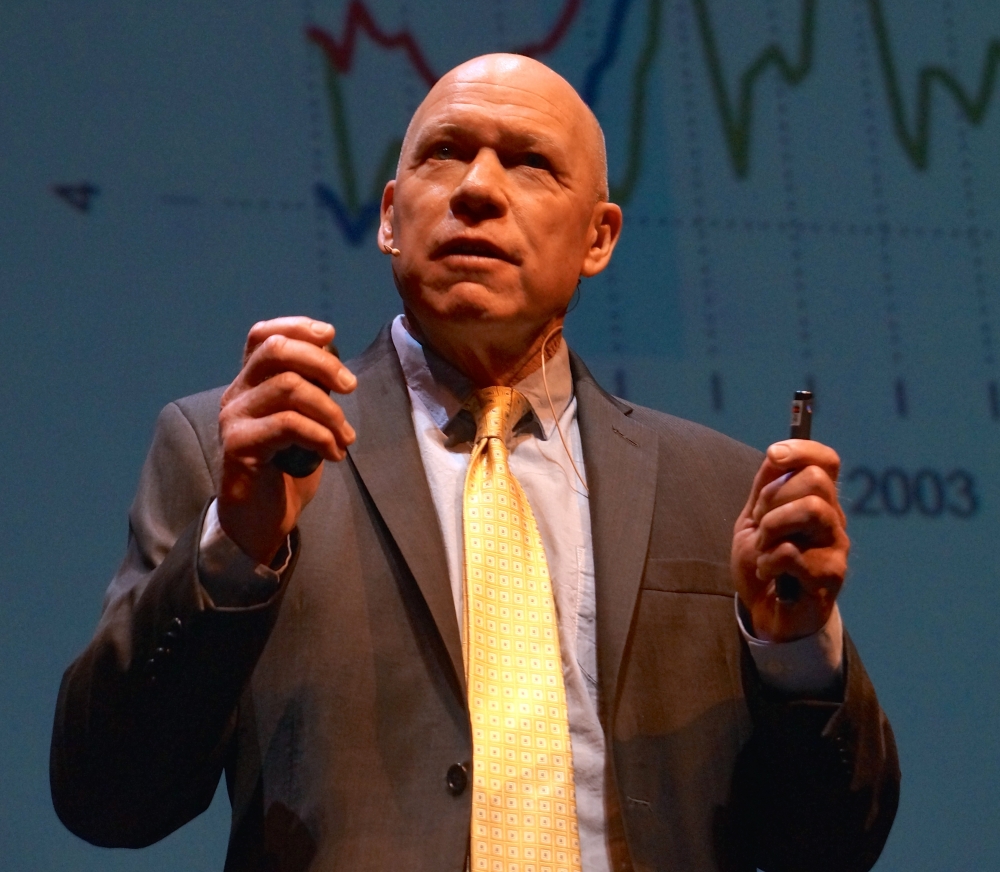

The national economy is also recovering slowly. Michael Bryan, vice president and senior economist in the research department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, gave his own personal projection of 3 percent growth in gross domestic product in the coming few years. His prediction is more conservative than the 4 percent growth over the last three years predicted by the Fed. In reality, the growth rate has hovered around 2 percent, according to Bryan.

“I’m pretty critical of economic forecasters,” he said. “But I think UCSB gets it right, in the sense that knowing how hard economic forecasting is, putting the information in the hands of people that need to know it, and doing it quickly, is invaluable.” Most economic forecasters don’t do that, he added, but UCSB, in his opinion “gets it exactly right.”

Among the factors Bryan suggests that could affect the economic projections are growth in the housing market, and business and consumer confidence. However, headwinds to the 3 percent growth continue to exist, he said. Among them is the continuing shock to household balance sheets caused by the recession, although they are in a strong position to recover. Households may still be taking on less debt despite low interest rates, and uncertainty around real estate and business might still be making potential investors and bog-ticket item purchasers skittish, though according to Bryan, things look like they’re returning to “roughly normal times.”

“This time there certainly looks to be a capacity for the economy to kick it up a notch,” he said.

The summit also featured a wide ranging and lively discussion on the future of work, with input from panelists Andrew McAfee, principal research scientist at the Center for Digital Business at MIT’s Sloan School of Management; Megan McArdle, a Washington-based journalist who writes about economics, business and public policy for Bloomberg View and other publications; and Lee E. Ohanian, professor of economics and director of the Ettinger Family Program in Macroeconomic Research at UCLA.

The panelists agreed that with the rise of technology come the dual effects of abundance and unequal distribution. Technology will benefit those who know how to use it and own it, but will take away employment from those who aren’t equipped to compete with it. While the panelists presented a range of perspectives — from McAfee’s pessimism about work as currently defined to Ohanian’s optimism that policy changes and education will allow people to catch up — they agreed that technology will not meet the needs of every aspect of the workplace, or the educational preparation for employment.

However, said panel moderator Russel Roberts, author and host of the EconTalk podcast, education will have to be less rigid and more innovative and stimulating to compete with technology-based learning. McArdle, meanwhile, noted that human interaction cannot be replaced.

“What you cannot reproduce is being a person,” she said, adding that the attitude toward service jobs and their value will need to change as technology becomes more sophisticated.

More data from the UCSB Economic Forecast Project can be accessed by visiting the Economic Forecast Project website. The entire panel discussion on the future of work will become available on the EconTalk podcast.