Declines in Large Wildlife Lead to Increases in Disease Risk

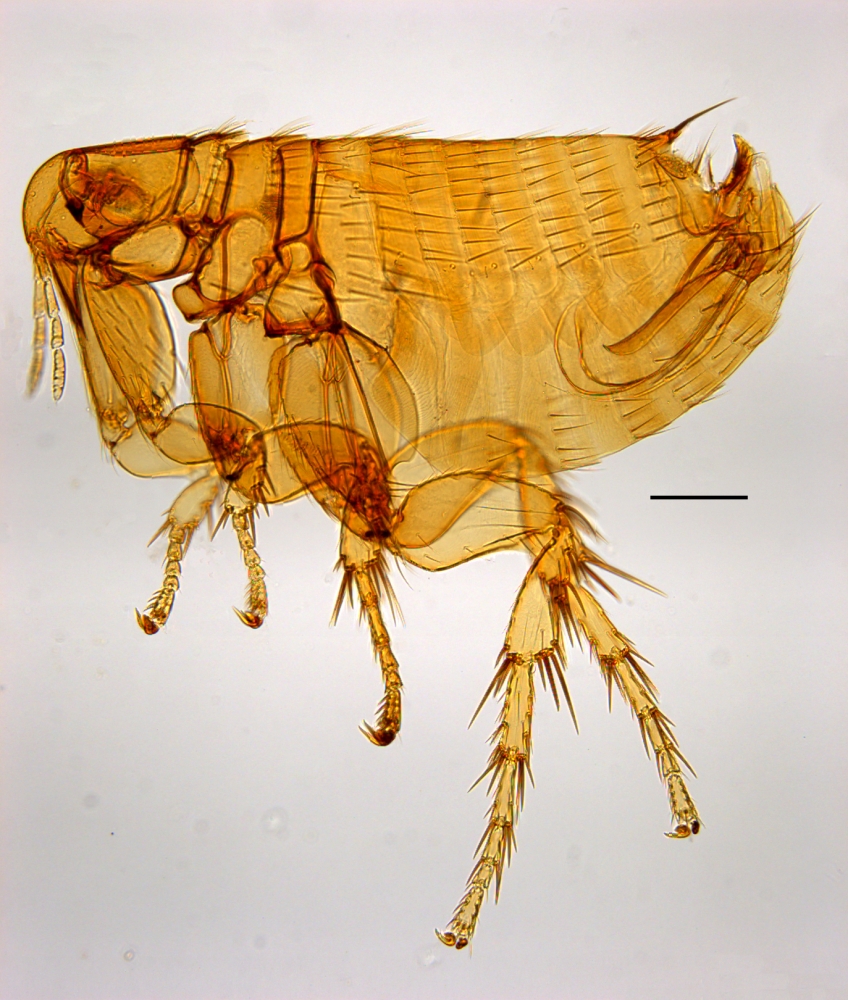

In the Middle Ages, fleas carried by rats were responsible for spreading the Black Plague. Today in East Africa, they remain important vectors of plague and many other diseases, including Bartonellosis, a potentially dangerous human pathogen.

Research by Hillary Young, assistant professor in UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology, directly links large wildlife decline to an increased risk of human disease via changes in rodent populations. The findings appear today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early Online Edition.

With an East African savanna ecosystem as their research site, Young and her colleagues examined the relationship between the loss of large wildlife — defaunation — and the risk of human disease. In this case, they analyzed Bartonellosis, a group of bacterial pathogens which can cause endocarditis, spleen and liver damage and memory loss.

“We were able to demonstrate that declines in large wildlife can cause an increase in the risk for diseases that are spread between animals and humans,” said Young. “This spike in disease risk results from explosions in the number of rodents that benefit from the removal of the larger animals.”

The researchers discovered this effect by using powerful electric fences to experimentally exclude large species like elephants, giraffe and zebra from study plots in Kenya. Inside these plots, rodents doubled in number. More rodents meant more fleas, and genetic screens of these fleas revealed that they carried significantly numbers of disease-causing pathogens.

The study was concentrated in an area where rodent-borne disease is common and sometimes fatal. According to Young, these rodent outbreaks and associated increases in disease risk may be exacerbating health problems in parts of Africa where diminishing wildlife populations are rife.

“This same effect, however, can occur almost anywhere there are large wildlife declines,” Young said. “This phenomena that we call rodentation — the proliferation of rodents triggered by large wildlife loss — has been observed in sites around the world.”

Downturns in wildlife numbers can cause rodent increases in a variety of ways, including by providing more access to food and better shelter. “The result is that we expect that the loss of large animals may lead to a general increase in human risk of rodent borne disease in a wide range of landscapes,” Young said.

“In this study, we show the causal relationship between disturbance and disease is alarmingly straightforward,” she added. “We knock out the large members of ecosystems, and the small species, which generally interact more closely with humans, dramatically increase in number, ultimately brewing up more disease among their ranks.

The study provides ecosystem managers with yet another reason to protect large and at-risk wildlife species. “Elephants are an irreplaceable part of our global biodiversity portfolio,” Young said, “but they also appear to be circuitously protecting us from disease.”

Also involved in the study was Douglas J. McCauley, assistant professor in the Department of Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology at UC Santa Barbara. Other participants were Rodolfo Dirzo of Stanford University; Kristofer M. Helgen of the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution; Sarah A. Billeter, Michael Y. Kosoy and Lynn M. Osikowicz of the Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Daniel J Salkeld of Colorado State University, Fort Collins, and the Woods Institute for the Environment at Stanford University; Truman P. Young of UC Davis; and Katharina Dittmar of the University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.