Beyond The Beach Boys

Long before The Beach Boys made “Surfin’ USA” a 1960s national anthem and helped the surf music genre earn its own category in record stores, surfing music was riding the waves in its native Hawaii. Mele — surf chants — about surfing date back at least as far as the 18th century, when surfing was a highly ritualized activity enjoyed by Hawaiian royalty and commoners alike.

King Kalakaua, who ruled Hawaii from 1874 to 1891, had his own surf chant, as did Emma, the queen consort of King Kamehameha IV some 40 years earlier.

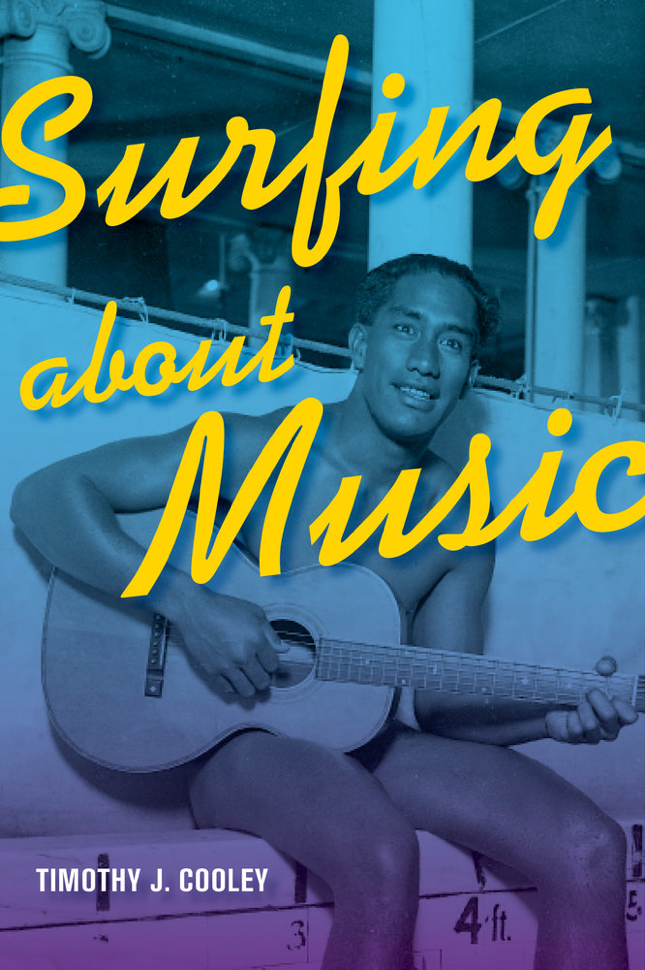

In his new book, “Surfing About Music” (University of California Press, 2014), Timothy J. Cooley, an associate professor of ethnomusicology at UCSB, studies the interrelationships between music and surfing and explores the different ways surfers combine surfing with making and listening to music. Drawing on his knowledge and experience as a practicing musician and an avid surfer, he considers the musical practices of surfers in locations around the world, taking into account ideas about surfing as a global affinity group and the real-life stories of surfers and musicians he encounters.

“My students introduced me to the idea of music and surfing as a research topic,” he said. “I made connections — I listened to music going to the beach — but it hadn’t occurred to me that there were surf bands that we still having an impact on these young surfers.”

Cooley begins his survey of surfing music with a study of Hawaiian surfing chants. “Much of what we know about pre-revival surfing comes to us from Hawaiian legends and mele — the original surfing music,” he writes. “Since at least the surviving mele tend to focus on Hawaiian nobility, they skew our picture of surfing history a bit. However, Hawaiian legends and early accounts by Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians leave no doubt that just about everyone surfed — royal and commoner; men, women, and children.”

From there, Cooley explores Hawaiian popular music of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “They were called hapa haole — half foreign or white — songs and they became a Hawaiian tradition,” he said. “These were Tin Pan Alley-type songs, some written in New York, but most were written in Honolulu. There are a few songs about surfing in Hawaii, and Hawaiian women are emphasized.”

The quintessential California surf music — The Beach Boys, Dick Dale (aka the King of the Surf Guitar), the Bel-Airs, The Chantays (known for the instrumental “Pipeline”) and The Surfaris — represented a watershed moment in surfing history, according to Cooley. “All of a sudden it’s associated with California as well as Hawaii,” he said. “Culturally, surfing shifted to the mainland. Before that, surfers in California were referencing Hawaii with their music and their mythologies — and we still do. But there’s an important shift, and it’s marked by surf music.”

And that music marked a problem for surfers. The naming of the genre became an issue, Cooley explained, because surfer-musicians were then expected to write or perform instrumental rock music or songs about surfing that followed the style of The Beach Boys or Jan and Dean (think “Surf City” and “Deadman’s Curve”).

By the mid-1960s, however, surf music was beginning to wane. Cooley attributes this to a number of factors, including the emergence of The Beatles, but added that other factors also came into play. “There was a different cultural emphasis for young people during the rise of the civil rights movement and growing opposition to the war in Vietnam,” he said. The surf hits didn’t have the political angst that began to define the later 1960’s.”

According to Cooley, it wasn’t until another UCSB connection — alumnus Jack Johnson — had somewhat accidental success as a musician that surfer/musicians, or musician/surfers experienced a rebirth of sorts. “He was a film studies major here at UCSB,” he said of Johnson. “His first career was as a semi-professional surfer and his second career was making surf films. He put one of his own songs on a film and his career as a musician began. It wasn’t until then that surfers realized their individual musicianship had value or was welcome in a way other than that of big bands like The Beach Boys. That’s almost 40 years — from 1961 to 2000.”

Cooley added that an interesting trend has developed with professional surfers creating second careers as professional musicians. Jack Johnson is one, Tom Curren another and Donavon Frankenreiter and Stephanie Gilmore still others. “This is an interesting moment,” Cooley said. “Part of it has to do with clever songwriting, and part of it has to do with extending one’s own personal brand through presenting yourself as a musician. And there’s some good music being made."