Visualizing Faulkner

Known for his experimental style, which often ran toward stream-of-consciousness, even punctuation-free prose, revered American author William Faulkner is a notoriously tough read. For the persistent, though, the Southerner's work can be as rewarding as it is challenging, elucidating life in his native Mississippi — and sometimes the human condition itself — with his meticulous, nuanced, and vivid writing.

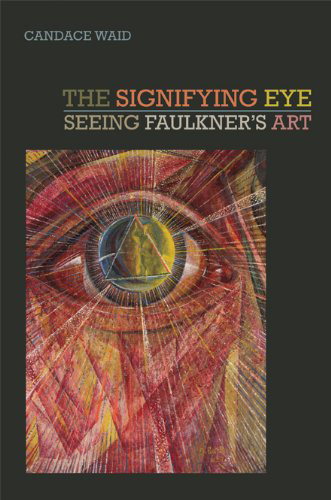

Not just vivid, but visual, and in fact inspired by Faulkner's own "visual obsessions," posits Candace Waid, a professor of English at UC Santa Barbara, in her new book, "The Signifying Eye: Seeing Faulkner's Art" (University of Georgia Press, 2013). Built around close readings of Faulkner's works both major and lesser-known, as well as some previously unpublished, Waid's take is described as both "visionary and revisionist."

"The Signifying Eye" shows Faulkner's art take shape in sweeping arcs of social, labor, and aesthetic history. Reading his work next to writers including Edith Wharton and Willa Cather, and painters Willem de Kooning and Aubrey Beardsley, among others, Waid reveals the author's visual obsessions with artistic creation. Some of Faulkner's own early drawings and illustrations also figure prominently.

"People are often surprised by the young Faulkner and his gifts as a visual artist," said Waid. "Scholars of the visual say that if someone has practiced one form of art, this medium will carry over, color the new art form that shapes their lives — and so Faulkner emerges as this complexly visual artist in words. Faulkner himself said — this is a paraphrase — that he wanted his work in 100 years to be able to stand up on its hind legs and cast a shadow."

Waid's own work may one day do the same. A literary scholar who teaches several Faulkner-focused undergraduate and graduate seminars, as well as a popular and provocative lecture course, "Southern Literature: Language and Culture," she just won The Faulkner Journal's Jim Hinkle Memorial Prize. Awarded only once every five years, the plaudit is reserved for a single essay, published in The Faulkner Journal, seen as making a unique and lasting contribution to Faulkner scholarship.

Waid has previously published a book about Edith Wharton, and works extensively on Eudora Welty, Charles Chesnutt, Mark Twain, Zora Neale Hurston, Jean Toomer, Richard Wright, and others. She is currently completing another book, "Blood Union: The Great American Novel of Liberation," which examines the arts in Southern literature more broadly in terms what she sees as the confrontational juxtaposition of oral and written narratives.

In "The Signifying Eye," Waid pictures Faulkner as a Southern modernist who bridges the region's oral traditions and literature with his avant-garde approach to writing. Further, noted one reviewer, Waid's book "develops into a meditation on the unique visions of experience that give modern American writing and painting their distinctive character and appeal."

Some two decades in the making, the book is, for Waid, a culmination of her devoted study of Faulkner, a passion for visual arts — and a handful of revelations related to both — that solidified her premise that Faulkner's own visual proclivities are a defining force in his writing.

"Writing and working on this book, one of the things that struck me was literacy — the electric experience of a new form of literacy — which I experienced in looking at a representation of a Willem de Kooning painting called ‘Light in August,' named for Faulkner's 1932 novel that foregrounds racial ambiguity," Waid said. "Seeing the novel playing itself out in a circular form, in varying perspectives, the painting spoke — and what it had to say was stunning. I'm drawn to painting and the materiality of the visual, and I think that's what drew me to Faulkner."

An excerpt from "The Signifying Eye" is published in the new edition of the journal Southern Spaces.