When President George W. Bush used the term "axis of evil" in his 2002 State of the Union Address and named North Korea among the world's worst perpetrators of aggression, Suk-Young Kim felt a chill run down her spine. A doctoral student at Northwestern University, Kim was working on her dissertation, which examined propaganda performances in communist China and North Korea.

"Suddenly there was this frenzy about North Korea in the mainstream media that so severely distorted how the very complex country works as a nation-state," Kim said. "It was very appalling and scary to see."

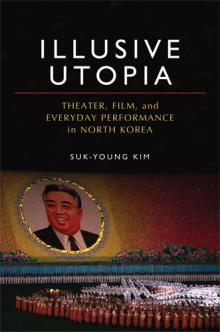

Now a professor of theater arts at UC Santa Barbara, Kim used material from her dissertation as the foundation for a book that analyzes how art practices –– mainly film, live productions, and large-scale propaganda performances –– serve as tools to regulate North Korea's collectivist society and provide a certain internal logic. That book, "Illusive Utopia: Theater, Film, and Everyday Performance in North Korea" (University of Michigan Press, 2010) has garnered Kim the prestigious James Palais Book Prize from the Association for Asian Studies.

Awarded annually since 2010, the prize is named for the pioneering Korean studies scholar, and recognizes an outstanding English language book from any discipline in the social sciences, humanities, and fine arts that addresses some aspect of Korean studies. Kim received the award last week at the association's annual conference in San Diego.

"I feel particularly honored because Korean studies is mostly dominated by political scientists, historians, and literary scholars," said Kim. "Performing arts comprise a tiny area within the field. The Palais Prize recognizes my particular discipline, and I'm happier about that than anything else."

Kim, who was raised in South Korea, said her primary goal with the book is not to normalize North Korean society, but to understand the art practices and how they create an ideal image of the nation. "The idea of collectivism is very different when we look at it from their perspective as opposed to our own," said Kim. "And the idea of social collectivism is fostered through participating in mass performances."

One such performance is presented in the book cover art. What appears to be a photograph of Kim Il-sung is actually a detailed image created by hundreds of thousands of placards held by an equal number of individuals sitting in a stadium. "You have to have a completely coordinated mindset to perform something like that," Kim explained. "And those images change instantaneously and continuously. It's mind-boggling and spectacular to see something so complicated.

"The form itself is very interesting –– if you leave aside the aesthetic judgment of what is beautiful and what is pleasing to our senses," she continued, "and just look at how it works as a kind of social machinery. How does that work, and what does it mean in terms of maintaining that society?"

In "Illusive Utopia," Kim examines how the country's visual culture and performing arts set the course for the illusionary formation of a distinctive national identity and state legitimacy. She illuminates the deeply rooted cultural explanations as to why socialism has survived in North Korea despite that fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and China's continuing march toward economic prosperity.

One of the challenges Kim faced in studying North Korean theater, film, and performance was to put aside her own bias. "The bias is scary," she said. "Our primary response is to ask how can anyone live in a place like that. But that's a very simplistic approach. What I figured out is that even in collective performances that seem to turn human beings into something resembling machines, there also seems to be a sense of community that's holding people together."

For Kim, a study of North Korean society is as much a lesson in our own sensibilities. "By looking into North Korea, we're also looking into ourselves. As critical as we are of North Korea, we should apply equally critical measures in looking at ourselves," she said. "I learned a lot about South Korean society while writing this book, even though it's about North Korean state propaganda. I also had a reflective moment of what I was subject to –– and what I was not allowed to see –– living in that society."

Related Links