It's a scandal replete with sex, drugs, and violence. Oh, and scientists, which is where Napoleon Chagnon comes into the picture.

Chagnon, professor emeritus of anthropology at UC Santa Barbara, retired from teaching in 1999 and now lives in Traverse City, Mich. But his name is surfacing again in international news and academic circles because a controversy started by "Darkness in El Dorado: How Scientists and Journalists Devastated the Amazon" –– a book written by Patrick Tierney more than nine years ago –– won't go away.

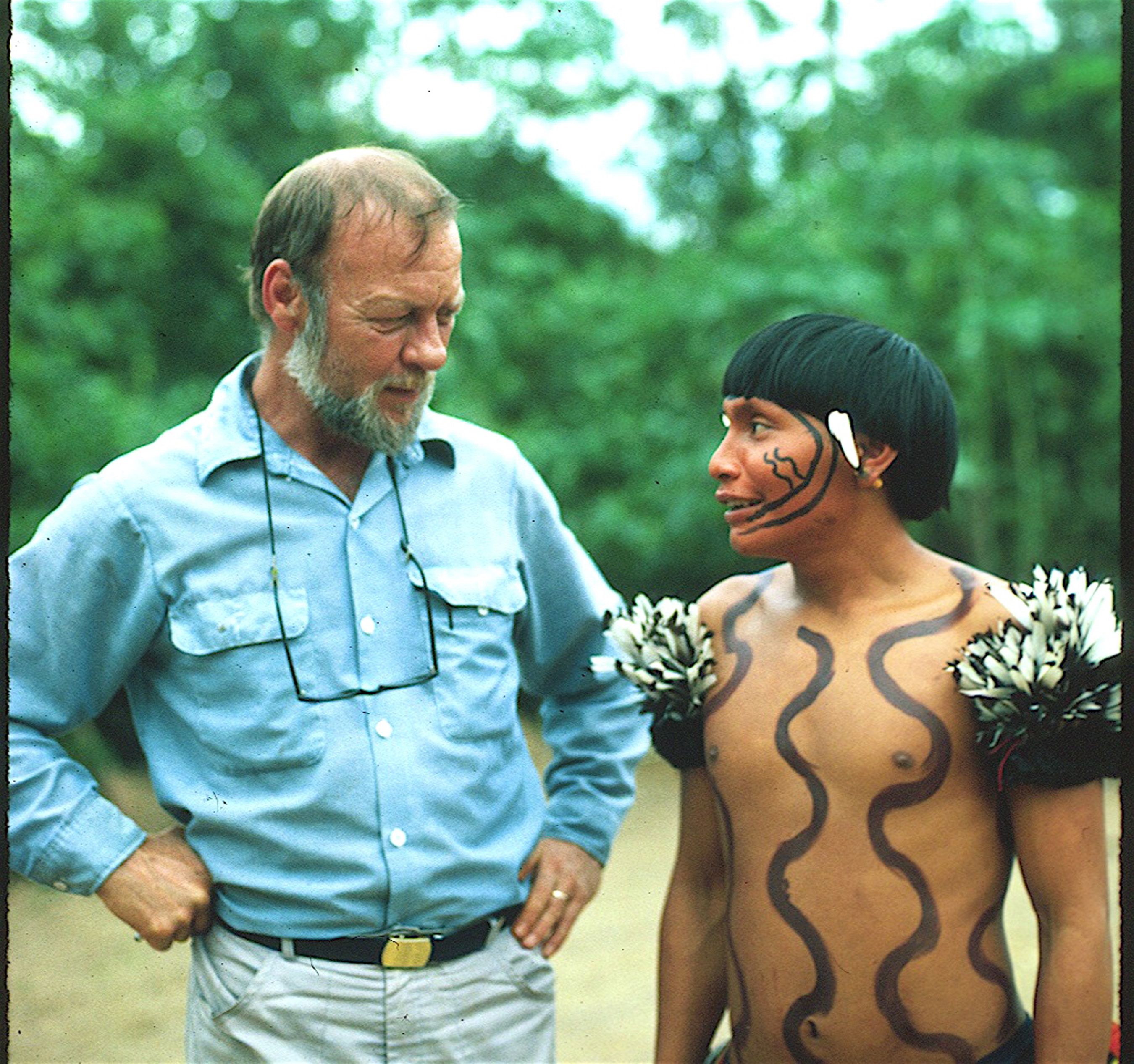

The strife is based on Chagnon's 35 years of research on the Yanomamö Indians, a tribe located on the border of Venezuela and Brazil. In one of Chagnon's early books, "Yanomamö: The Fierce People," the author described a society permeated by violent warfare, which dominated all facets of life, including marriage, sex, and politics. In "Darkness," Tierney accused Chagnon and colleagues of deliberately starting a measles epidemic among the Yanomamö.

What's bringing all of this to the forefront again are two developments: an article in the Dec. 11, 2009, issue of the journal Science, and the upcoming premiere of "Secrets of the Tribe," a film by Brazilian director José Padilha. The film will debut Jan. 22 at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah.

"It is now heating up again," Chagnon said of the longstanding controversy. "People seem to love conspiracy theories that involve scandals and deceptive scientists who do harm to hapless, hopeless, homeless, and harmless native peoples who guard the Amazon Basin and preserve it for the rest of us."

Padilha's film is certain to generate interest in the Yanomamö imbroglio. A promo for "Secrets of the Tribe" on the Sundance Festival web site says this of the film: "The field of anthropology goes under the magnifying glass in this fiery investigation of the seminal research on Yanomami Indians. In the 1960s and '70s, a steady stream of anthropologists filed into the Amazon Basin to observe this ‘virgin' society untouched by modern life. Thirty years later, the events surrounding this infiltration have become a scandalous tale of academic ethics and infighting."

"One of the most important things in science is skepticism, the idea that we should not accept theories and beliefs as being true at face value," Padilha said in an interview via e-mail. "In science, we must demand beliefs and theories that are testable empirically, and we need to confront those theories with the available empirical basis in a sound methodological way before appraising them as tentatively true. I think that my film shows that in the case of the Yanomamö studies and controversies, the anthropological community did not behave this way."

Chagnon has denied all charges and points to the recent article in Science by Charles C. Mann, entitled "Chagnon Critics Overstepped Bounds, Historian Says," as evidence that he and others believe that the anti-science anthropologists had conducted a "veritable witch hunt of me and one of my collaborators (geneticist James V. Neel, who is now deceased)."

In 1967, Neel's laboratory determined that the Yanomamö had not been exposed to measles and the research team brought vaccines with them to Venezuela in 1968 as a humanitarian component in their field studies that year. According to Tierney's book, their vaccination efforts exacerbated an epidemic of measles that had just begun and caused "hundreds if not thousands of deaths" among the Yanomamö. The American Anthropological Association (AAA) launched an inquiry into the charges. The investigators exonerated Chagnon and Neel, as had several other national academic associations that investigated Tierney's accusations, including the National Academy of Sciences. However, the AAA also concluded that Tierney's allegations "must be taken seriously," adding that Chagnon's work "had been damaging to the Yanamamö."

In the Science article, historian Alice Domurat Dreger of Northwestern University is quoted as saying that AAA's actions were so problematic that "I can't imagine how any scholar feels safe" as a member. The story follows a Dec. 2 meeting of the Anthropology Association in which a panel discussion was held to reexamine "Darkness." Just like a meeting held 10 years earlier, this gathering dissolved into rancorous debate, with arguments "spilling into the hallways," according to the Science article. Only this time, most of the criticism was leveled at AAA, and not at Chagnon.

Padilha said that he was not aware of Chagnon's role in the controversy prior to being asked to make the film by the BBC.

"The more I read about the subject," Padilha said, "the more I realized that some of the fierce controversies revolving around such studies had a lot to do with academic politics and with the lack of sound methodological procedures to decide what could and could not be accepted as scientifically valid in the field of Yanomamö anthropology. Since I am very interested in epistemology and philosophy of science, and I am a strong believer that the methodology of science is the best we have to evaluate attempts to understand nature, and to generate knowledge, I agreed to make the film."

Padilha said that he did not intend to prove Chagnon's innocence, or guilt, with his film. "My goal was not to evaluate individuals or charges against individuals," he said. "I have my personal opinions about those, but my opinions are not in the film itself. The film is totally made out of statements made by the anthropologists and Yanomamö Indians."

After the premiere at Sundance, Padilha hopes to have his documentary aired on HBO, BBC, and other television channels later this year. Padilha said he's very grateful to Chagnon for the professor's contributions to the movie, including providing many hours of Chagnon's own films of the Yanomamö that he recorded during his years of research.

"Professor Chagnon really contributed a lot to the film," Padilha said. "I cannot begin to tell you how much so. He gave me access to amazing footage, and that really made a big difference to me."

Chagnon added that Science is planning a second, more extensive article about the Yanomamö controversy in February. And then, later this year, Simon & Schuster will publish Chagnon's book, "Noble Savages," which he says will be a descriptive and philosophical retrospective on his 35 years of studying the Yanomamö Indians.