The phrase “locally sourced” usually refers to food. But in the case of artist Sandy Rodriguez, it actually applies to her paints.

Rodriguez, whose latest site-specific exhibit, “Unfolding Histories — 200 Years of Resistance,” is on view at UC Santa Barbara’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum, personally fabricates plant and soil-based paints to create images that are grounded in a particular place — in this case, California’s Central Coast.

The Los Angeles-based artist, whose work has been displayed in major museums including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Denver Art Museum and the Huntington Library, spent months researching the history and botany of this area. Among her excursions was a four-day trip to the Channel Islands.

“It was glorious,” Rodriguez said. “We were driven around the island, where we could observe plants that exist nowhere else in the world. We also visited archeological sites. I got to sit and draw and go on beautiful hikes.

“I returned home — with permission, of course — with a handful of very beautiful plant and soil samples, which I then created paints from. Colors from that process are included in the objects you’ll see in the show.”

Those colors — including deep reds and a particularly vibrant teal — have a unique beauty. But her work is not simply about providing aesthetic pleasure. In many of her pieces, Rodriguez draws attention to protest movements past and present, juxtaposing imagery in a way that suggests resistance to oppression is a long and continuing story.

“Sandy blends the past and the present,” said Sophia McCabe, curator of the exhibition. “She tells the story of California history from the perspective of the colonized. This history is often left out of Western history books.”

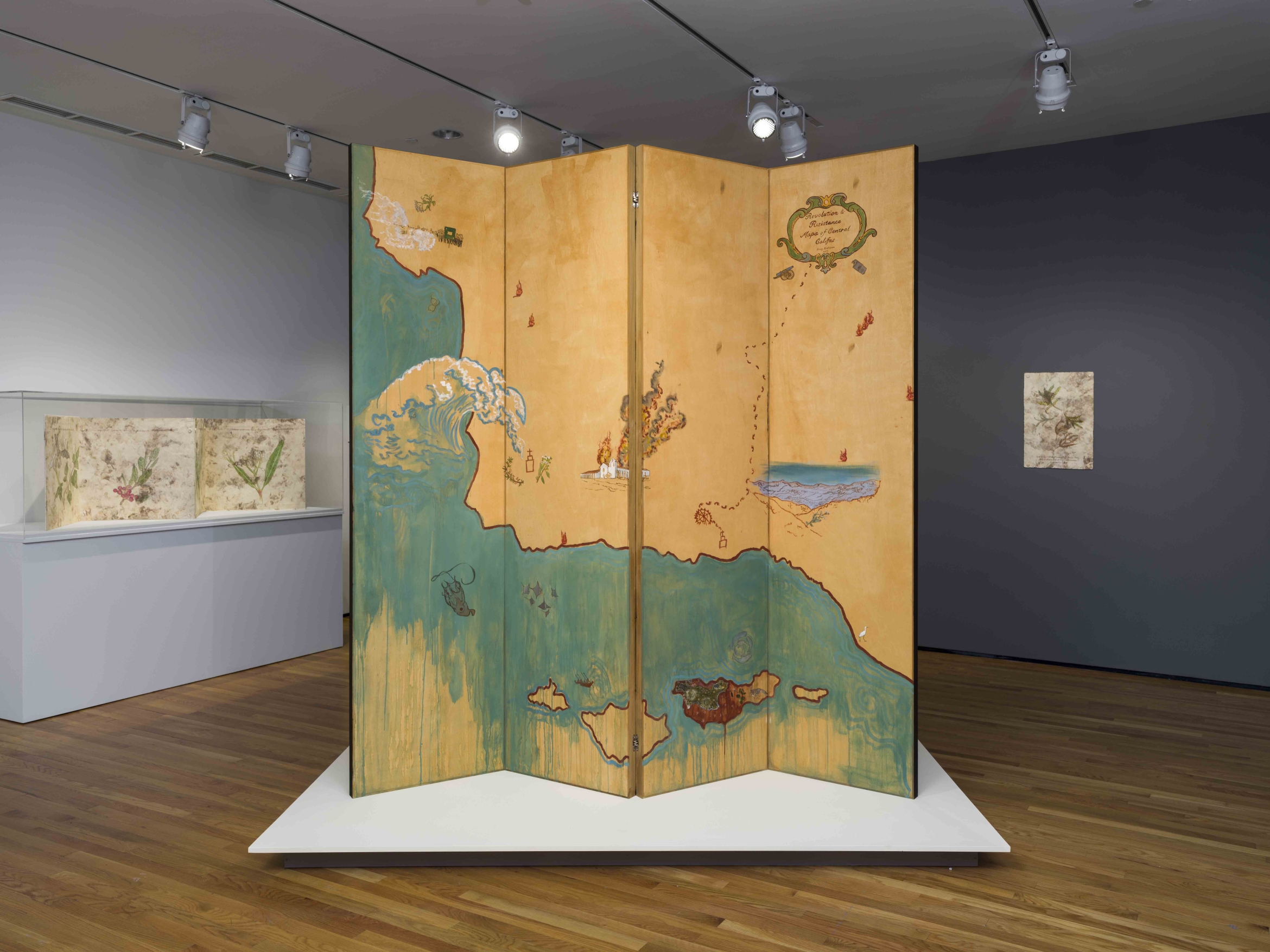

The centerpiece of the UC Santa Barbara show is a “monumental double-sided maple folding screen,” Rodriguez said. “One side is the nighttime view looking at Santa Barbara from the Channel Islands, all done in hand-crafted charcoal. It’s a sparkly and reflective nighttime sky. I inlaid about 300 small pieces of abalone to create the stars, and used handcrafted oil paints to create something more enduring.

“The other side uses the soils from Santa Cruz Island, which gives it a warm, earthy tone. On that side, I painted a map of Central California, highlighting sites of resistance spanning 200 years.”

Through the work, Rodriguez draws attention to a largely forgotten piece of local history: The Chumash Revolt of 1824. That year, the native peoples of this region rebelled against the Spanish and Mexican colonizers who controlled the area.

Rodriguez commemorates this event by both referencing it on the map, and including in the exhibition a painting of Mission Santa Ines on fire. These images are juxtaposed with others depicting more recent acts of rebellion, including the protest marches following the 2020 murder of George Floyd.

“Sandy’s paintings critique the legacy of colonization,” McCabe said. “She brings together historical and present-day events, showing how we have arrived at this moment.”

Originally from the San Diego area, Rodriguez comes from a family of artists. “There’s my grandfather, my grandmother, my mother, myself — and I suspect it went back a bit further,” she said. She knew from a young age that she was destined to go into the family business.

“I was 16 when I was recruited to attend the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts,” she recalled. “I was overjoyed that I could do my English, math and history all before noon, and then be in the studio from noon to 3 p.m. That felt so right!”

Before turning to full-time art-making, Rodriguez spent two decades working at various art museums. She reports this experience contributed to her growth as an artist. “Part of my museum work was teaching studio courses,” she said. “So I used studies by masters like Degas and Courbet and thought about their use of line. My work draws on those influences. It’s an intentional mixing of the European tradition with traditions from the Americas.”

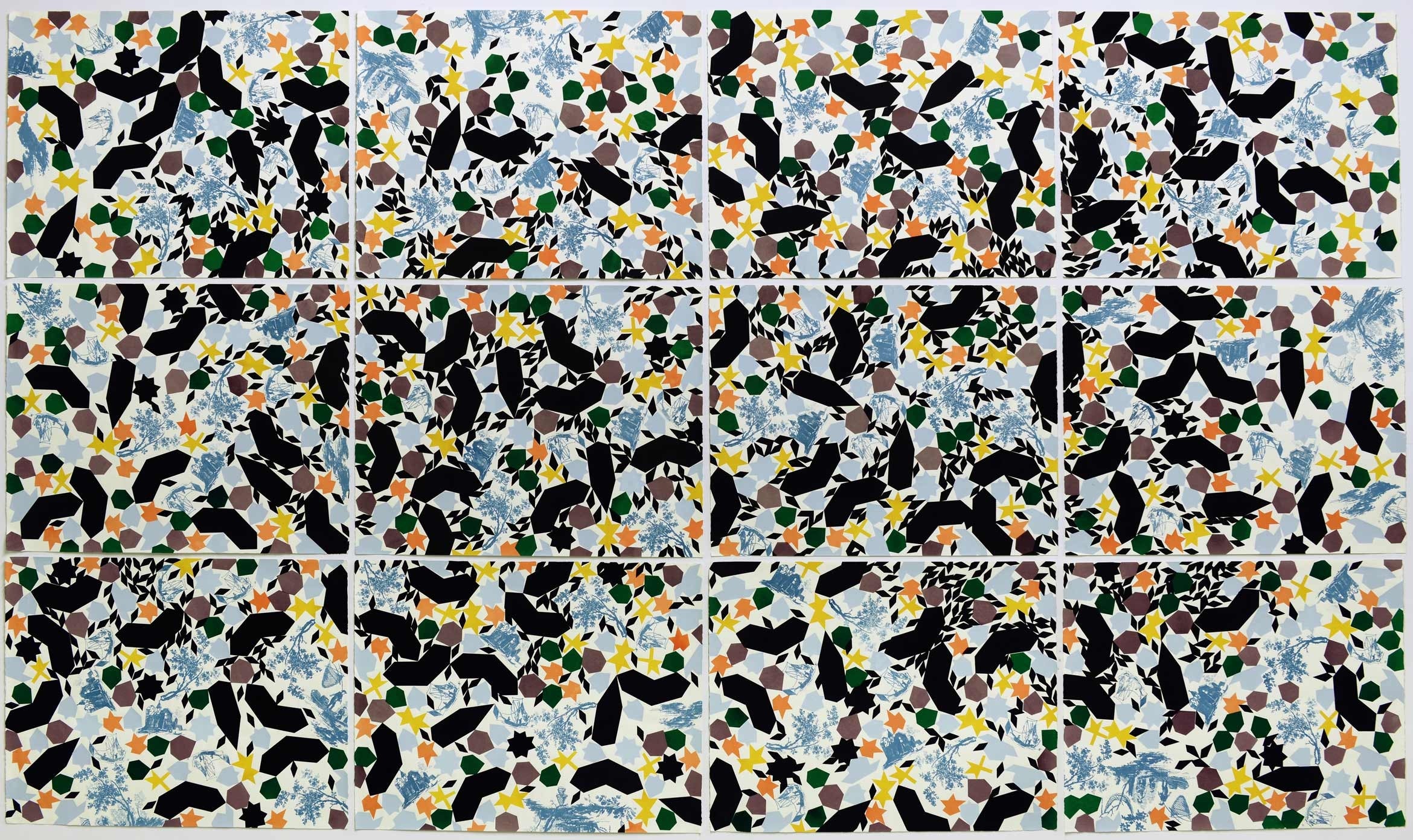

Her most direct influence is the Florentine Codex, an encyclopedic study of the people and plants of colonial Mexico put together by Franciscan missionaries in the 16th century. Rodriguez uses that work as a template, creating new paintings on the same ancient form of bark-based paper used for codexes. Among the paintings she produced for this exhibit are several depicting native flora that are unique to this region.

“This is my first sustained engagement with the Central Coast,” she said. “It has been really transformative. The conversations with artists, historians and people with such diverse backgrounds as anthropology and sociology to ethno-botany have just been incredible.”

Utilizing that background information, Rodriguez creates beautiful works that reveal some ugly facts about our region’s past — and show how timeless notions of freedom and equality still resonate today.

“One of my strategies is to seduce and engage the viewer, and then to introduce conversations we’re not likely to have unless we’re engaged,” she said. “We have to confront the reality of the time we are living in, and understand how we got here. We can link the past and the present to see the future.”

Debra Herrick

Associate Editorial Director

debraherrick@ucsb.edu