Humanities program brings courses in literary studies to individuals in the California state prison system

It’s not the typical classroom situation, but then, these are not typical students. Their life journeys have taken them not to colleges and universities, but to one of the 34 facilities within California’s prison system. Most of them are serving life sentences.

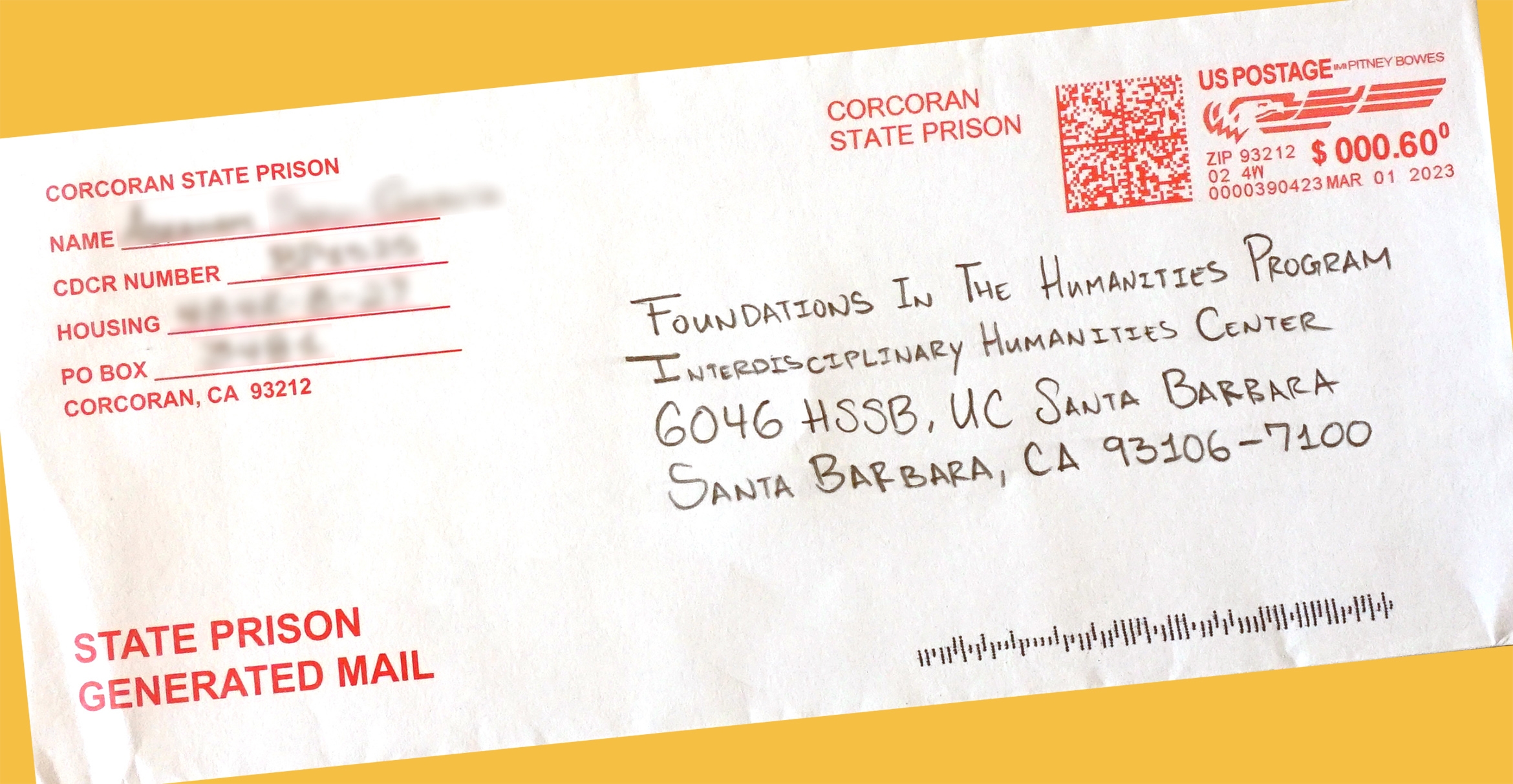

And they are participating in Foundations in the Humanities, a correspondence program of UC Santa Barbara’s Interdisciplinary Humanities Center (IHC), where they explore the world of literature and broaden their perspectives in the process.

“Right now, we have 121 students,” said Susan Derwin, director of the IHC and a professor of comparative literature. “We’ve had as many as 160.” The waiting list currently stands at 275, and Derwin expects it to reach 400 this summer. Since the program began in 2016, it has served 873 participants.

And now it has garnered special attention from the California State Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, which has awarded Foundations in the Humanities a three-year Innovative Programming Grant to work with 60 incarcerated individuals at the California Men’s Prison-Corcoran.

The grant covers the cost of instructors who work with the participants, as well as two visits per year to the Corcoran facility.

“This award is significant because Foundations does not have an ongoing source of funding that fully supports the program,” Derwin said. “Equally important, it legitimates the educational value of the program in the eyes of the state and establishes our credibility with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. We hope this will enable us to bring more educational programming to people who are incarcerated in California.”

IHC Assistant Director Chris Bovbjerg, who manages the program, notes that Foundations in the Humanities offers three courses: “Foundations I: Introduction to Literary Studies,” “Foundations II: Selected Works of American Literature” and “Foundations III: Studies in the Novel.” The courses comprise six modules that each contain a short reading and an accompanying worksheet with six essay questions. According to Bovbjerg, each reading presents situations in which fictional characters confront and respond to significant life situations and challenges of universal relevance. Reading and responding to questions about these literary works enables participants to expand their insight into themselves and their society, for the purpose of building better lives in prison and after their release.

Derwin began developing Foundations in Humanities when a former student who had become incarcerated contacted her about creating a humanities program at the facility where he was confined. Getting a program off the ground proved difficult, however — it was a tough sell to the prison wardens and community resource managers she initially contacted.

Fortunately, she found an ally in Sister Mary Sean Hodges, who runs the Partnership for Re-Entry Program, a series of life skills correspondence courses offered by the Archdiocese of Los Angeles County. The courses are designed to improve the odds of success for parolees creating new lives in their communities, and Hodges was already a fixture in the prisons.

“I was at a loss, so I contacted Sister Mary,” Derwin said. “She came to the IHC from Los Angeles with three co-workers, all of whom were formerly incarcerated men, and proposed that we become partners. That meant I was able to go into the prison with her and start to teach my classes.”

“I love the program of humanities,” Hodges said. “Almost everything all other programs do is prison related — how did I get here, what am I doing to get out of here? But the humanities take the participants to a new realm altogether — how can I be out of prison while I’m still here?

“We need this kind of programming because all of us need healing every day from our actions,” Hodges continued. “That comes from looking at our daily circumstances in a new light, looking back at where we came from and looking forward to where we can go. Susan’s programs offer these experiences of ‘where can I go’.”

According to Derwin, Hodges prefers to work with people who are serving life sentences because they are “on the path to rehabilitation,” and most of the Foundations in the Humanities students come from that cohort.

Some in the program are serving life sentences without the possibility of parole and have been incarcerated for decades. “They find this work incredibly important, because inside the facilities these individuals are often the leaders in the community,” Derwin said. “They set an example for the younger people who are incarcerated about how you live your life — you keep working on yourself, and developing yourself, and training yourself. They’re elders in the prisons. It’s a very articulated and nuanced society where intergenerational relationships have a great impact.”

At the time Foundations in the Humanities first began in 2016, Derwin was the sole instructor, joining Hodges on her visits to three prisons in the Central Valley and San Luis Obispo. “We worked with the men in her PREP program,” Derwin said. “I taught a seminar on several yards in each facility, and those who took part and were interested in studying literature through correspondence wrote to me.”

It quickly became clear, however, that demand was far more than one professor could manage. So Derwin recruited five humanities graduate students to work with her. “Before we knew it, we had hundreds of people applying to us to enroll,” she said. “That first year we had six graduate instructors and 65 students. And when we finished that class, the students wanted a second one. So, we started ‘Major Works in American Literature.’ And those students wanted a third class, so now we have ‘Studies in the Novel,’ with students reading Zora Neale Hurston’s ‘Their Eyes Were Watching God.’

“By the time the students are going into their third year, they are skilled, critical, reflective readers,” Derwin continued. “And the essay questions they’re given ask them to synthesize and analyze the readings from different perspectives, which they are well prepared to do.”

Foundations in the Humanities is now active in all 34 of California’s state prisons, and the number of incarcerated students accommodated depends on the number of graduate student instructors. Each instructor works with up to 15 students at various facilities. “This year we have had 12 instructors,” Bovbjerg said. “But we’re looking for as many as we can get.”

Until now, in addition to support from the Office of the Dean of the Division of Humanities and Fine Arts, funding for the program has come from the UC Humanities Research Institute and from UC Santa Barbara community outreach grants. Now, with the CA Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Grant, it is funded to run at Corcoran for three years.

Derwin visited the Corcoran facility last month. “We spent the day there teaching in two yards,” she recalled. “Inside yard 4B there’s a huge wall that has a beautiful image of a globe on a pedestal. Emblazoned across this mural are the words ‘Self-Help University.’ This yard had previously been the SHU, Special Housing Unit, where individuals were put into solitary confinement. The people on the yard decided to reclaim and repurpose it and make it theirs. It’s now Self-Help University, and they’re offering their own diploma inside.”

The effects of the Foundations courses ripple beyond the coursework. “It’s generated new kinds of conversations on the yard,” Derwin said. “People get together and talk about the texts. We encourage them to form study groups after they’ve completed their work, to continue the conversation.”

And those ripples extend beyond the facility itself, to participants’ relationships with their loved ones. “Almost everyone inside has relationships with some young people — children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews and cousins. The participants become role models,” Derwin continued. “They now talk to their loved ones as students. They model good practices.

“Engaging in the process of reading and thinking about the meaning of literature in relation to their own lives, they have more to talk about than what’s happening on the yard or what needs they may have. They have ideas to share, which is empowering and enables them to assume their responsibility in society beyond the prison walls. They experience themselves not as ‘inmates,’ but as thoughtful, socially engaged individuals who have something meaningful to contribute to other people’s lives.”

Shelly Leachman

Editorial Director

(805) 893-2191

sleachman@ucsb.edu