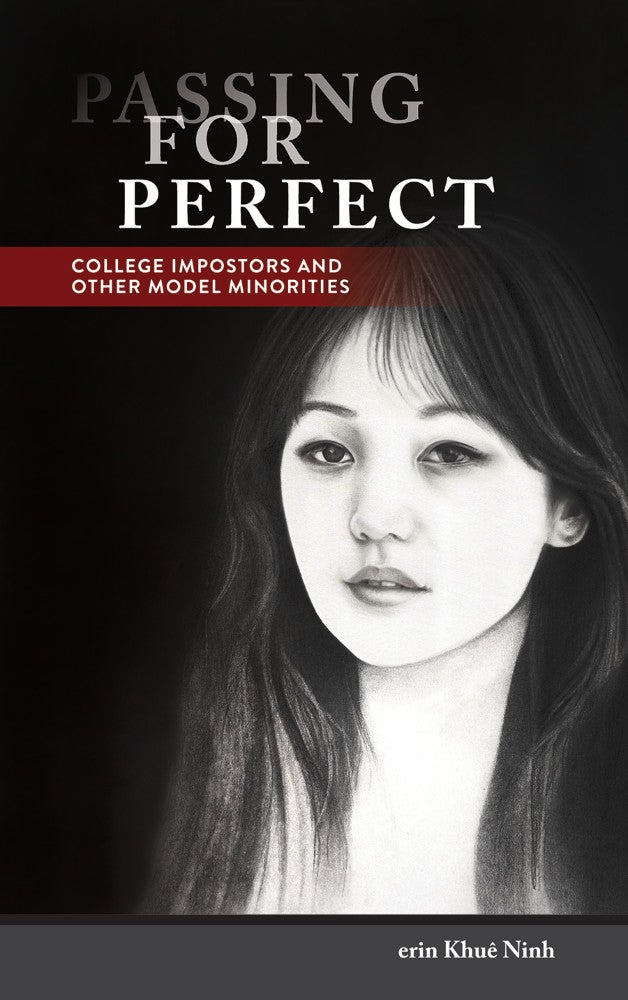

‘Passing for Perfect’

Azia Kim and Jennifer Pan were ghosts in plain sight. Kim lived like a Stanford student — studied, lived in dorms, hung out with friends, even attended ROTC training. Pan told her family she graduated from college and pharmacology school.

Both were frauds. Kim was discovered and kicked off campus after nine months. Pan hadn’t stepped foot in a classroom after high school. When her parents discovered the ruse she hired hit men to kill them.

How could this happen? Both young women appeared to be overachievers destined for the best schools and lucrative careers. It’s a question erin Khuê Ninh, an associate professor in UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Asian American Studies, explores in “Passing for Perfect: College Impostors and Model Minorities” (Temple University Press, 2021).

“Let’s call ‘college impostors’ people who pose as students at a particular college or university, usually a prestigious one,” Ninh said, but notes that not all impostors are created equal. She distinguishes between “scammers,” those looking for some material advantage, and “passers,” Asians “performing model-minority identity.”

The latter set, she said, “do this to no apparent economic advantage: They didn’t fake test scores or transcripts to gain admission; they were never admitted at all or maybe flunked out. Yet every school day for months or even years, they carry their laptops to the library and study, for exams they’re not going to take in classes they’re not enrolled in. They assiduously maintain this appearance of the high-performing student, for friends and family who believe they’re en route to shiny STEM degrees. Cheaters come from all racial groups, but all the baffling cases I’ve found have been Asian American.”

As Ninh relates, these impostors are almost all second-generation Asian Americans, the children of immigrants. All their lives they’ve been herded into what other scholars have called the “success frame” — an ever-running escalator to straight As, class valedictorian, an elite university and advanced degrees in one of the prestige fields of medicine, law, engineering or science.

In doing so, she said, these children of Tiger moms or helicopter parents maintain the appearance of being a “model minority” — the racialized expectation of success that becomes central to one’s identity. As Ninh writes, “the model minority is coded into one’s programming — racialization become feeling and belief — its litmus test is whether an Asian American feels pride or shame by those standards.”

The distance between pride and shame is excruciatingly close, and can be bridged by one bad grade — indeed, Jennifer Pan’s deception peaked when she failed a calculus course, and her early admission to university was rescinded. And when failure is unthinkable, doing the unimaginable can seem the only option.

Ninh, a second-generation Vietnamese American, is intimately familiar with the pressure of the success frame.

“These are desperate young people, whose faked college attendance really hurts no one but themselves,” she said. “What’s more, their foolish choices have generally been made out of fear of, deference to, or protectiveness toward someone else’s will or desire. Whether it’s a high school senior with a rejection letter or a pre-med major who has lost academic probation, what do you imagine it would take to have to hide that from everyone they know, for how long they have no idea? There’s a world of pressure and feeling to understand behind that.”

Impostors, she said, exist on a continuum of ethnicity and intent. Passers might not be trying to game the system, but they can still pay a terrible price.

“In the book,” Ninh said, “I use the term ‘passing for model minority’ to refer to both that very particular subset of college impostors — and also Asian Americans at large who have been raised and racialized into the same high-achiever role, with its very narrow conditions for a socially acceptable, parentally valued life.

“In my intro, I phrase the research question as, ‘How do well-behaved Asian Americans become people with no felt options?’ That framing of the problem describes not just my eccentric cases but so many of our students who navigate the future as if it has only a road to a lucrative career as a doctor or lawyer — or a terrifying blankness they cannot bear to contemplate.”