‘Ancient Egypt and Early China’

Anthony Barbieri knows it sounds a little strange to compare the New Kingdom of Egypt (ca. 1548-1086 BCE) with the Han dynasty of China (206 BCE-220 CE). They existed more than 1,000 years and nearly 5,000 miles apart — gaps that would seem to give pause to a scholar’s suspicion that the empires shared a cultural DNA largely missed by the rest of the world.

Undeterred, the UC Santa Barbara professor of history, who specializes in ancient China, dove into training like an Olympian. With the help of a $238,700 New Directions fellowship from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Barbieri became, for all intents and purposes, a graduate student in Egyptian archaeology and hieroglyphics at UCLA.

The result after seven years of study and research: “Ancient Egypt and Early China: State, Society, and Culture” (University of Washington Press, 2021), Barbieri’s groundbreaking comparison of the two civilizations.

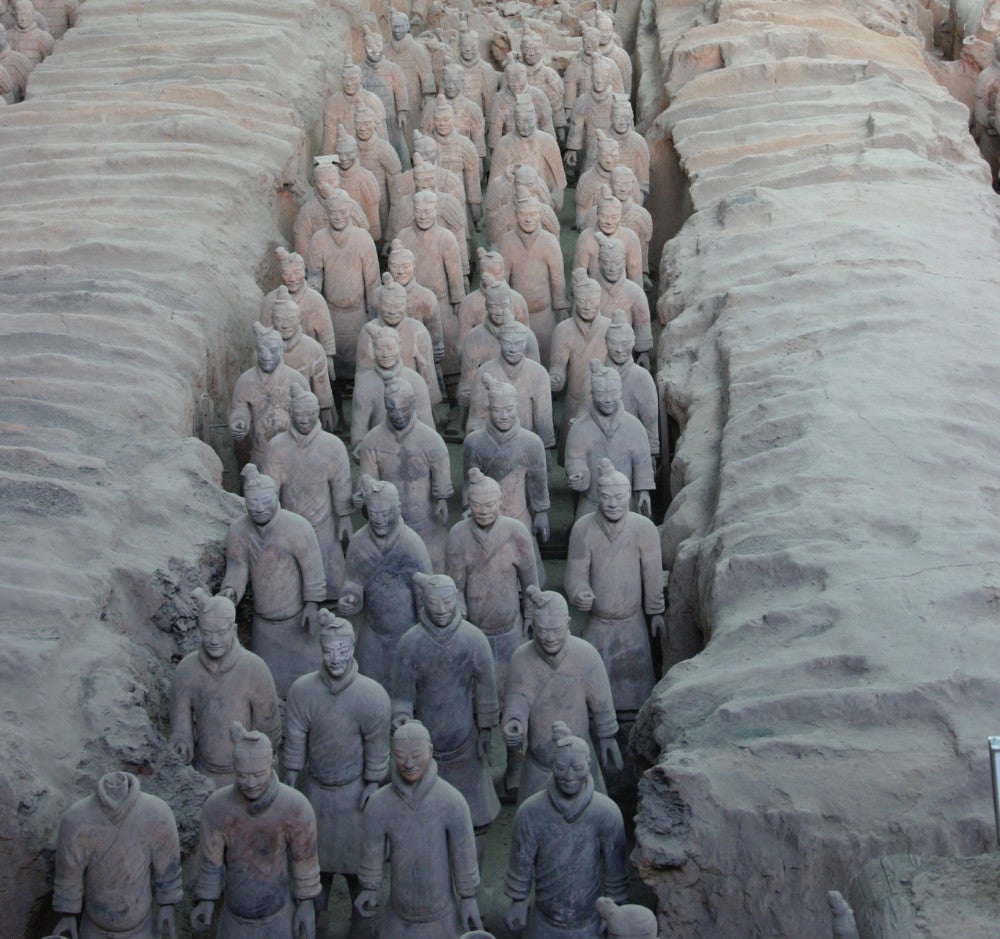

The similarities between New Kingdom Egypt and Han dynasty China are both stark and subtle. Both sat on river plains that required sophisticated management to feed their people; each relied on warfare and diplomacy to expand and maintain their empires; both had notorious leaders who enacted radical reforms and were later undone by overreach; each had a system of universal justice; both maintained a culture of highly trained scribes; each developed elaborate tomb models that provided for the afterlife; and both created board games that helped one find paradise in the afterlife.

Comparative studies of civilizations are not new. As Barbieri notes, multiple scholars have compared Roman and Greek societies with that of China. But those cultures were contemporaneous, allowing for the possibility of contact and influence. Not so with the New Kingdom and the Han dynasty.

“There’s no direct contact between the two, obviously, because the time-frame is skewed,” he said. “I did that intentionally because then you don’t get cross-contamination, which can hamper a cross-cultural comparison.”

So why compare New Kingdom Egypt and Han dynasty China? For Barbieri, two key reasons stand out: For one, he’s had a keen interest in Egyptology for many years. His education as a de facto grad student gave him the solid grounding he wanted. More importantly, he believes immersing himself in a new field allows him to avoid “the trap” of overspecialization, which can lead to a kind of academic tunnel vision.

As he has stated in an online lecture about the book, “One of the benefits of comparative study is to make what seems familiar, unfamiliar, to break oneself out of the routine of thinking that certain things about China or certain things about Egypt are normal or characteristic of those civilizations and to force oneself to think differently about the situation.”

Barbieri credits his graduate advisor at Princeton, Robert W. Bagley, who was fascinated by Egypt, for helping him think outside the China box.

“Even though he was a China specialist,” Barbieri said, “almost the only thing we ever read together was Egyptology or anthropology, because he said you have to read outside your field. He trusted me to teach myself about China, but he said, ‘You really have to read outside your field. You have to see what anthropologists and other people are doing.’ ”

Barbieri — who reads and speaks modern Chinese, reads ancient Chinese, Japanese and ancient Egyptian, and plans to learn ancient Greek — said that his study of Egyptology offered him new ways to think about China and led directly to his book, which is the first of its kind.

“As I was sitting in those classes at UCLA,” he said, “every time stuff would come up, I would always be thinking about China. What does this look like in China? Or how is this similar? How is this different than China? And so the book started writing itself in my head while I was in these classes. I realized that this would make a fantastic book that no one had ever attempted before.”