Windows on the Past

When the Santa Barbara Gazette published its first edition on May 24, 1855, the U.S. was coming out of a recession that followed the boom times of the Gold Rush. Then, like today, a number of people wanted to break up California into three states.

The editors of the Gazette, however, dismissed the proposal as a boondoggle designed to line the pockets of the ruling class. Politicians, they wrote, “are generally very shrewd people. They are able to see immense distances into the future. Division will create many more offices to be filled. Politicians are fond of office. All agree that it is a question of great importance to the prosperity of the State.”

Snark aside, the article opens a window into a history of crackpots and killers, fights over land and lamentations over the state of Santa Barbara’s rowdy streets. The Gazette was the city’s first newspaper, and published weekly until May 15, 1857.

And now all 104 editions of the paper are open to the public. The UC Santa Barbara Library has digitized the Gazette, with issues available through its Alexandria Digital Research Library.

Published by W.B. Keep & Co., of whom little is known, the Gazette was a four-page broadsheet that featured international, state and local news. The first year’s issues included a page in Spanish, but it was discontinued in the second year.

The Gazette came to UCSB from the Santa Barbara Public Library, which received a bound presentation copy from Charles Fernald in 1891. Fernald was a major figure in the late 19th century, serving as mayor of Santa Barbara, sheriff, district attorney and county judge.

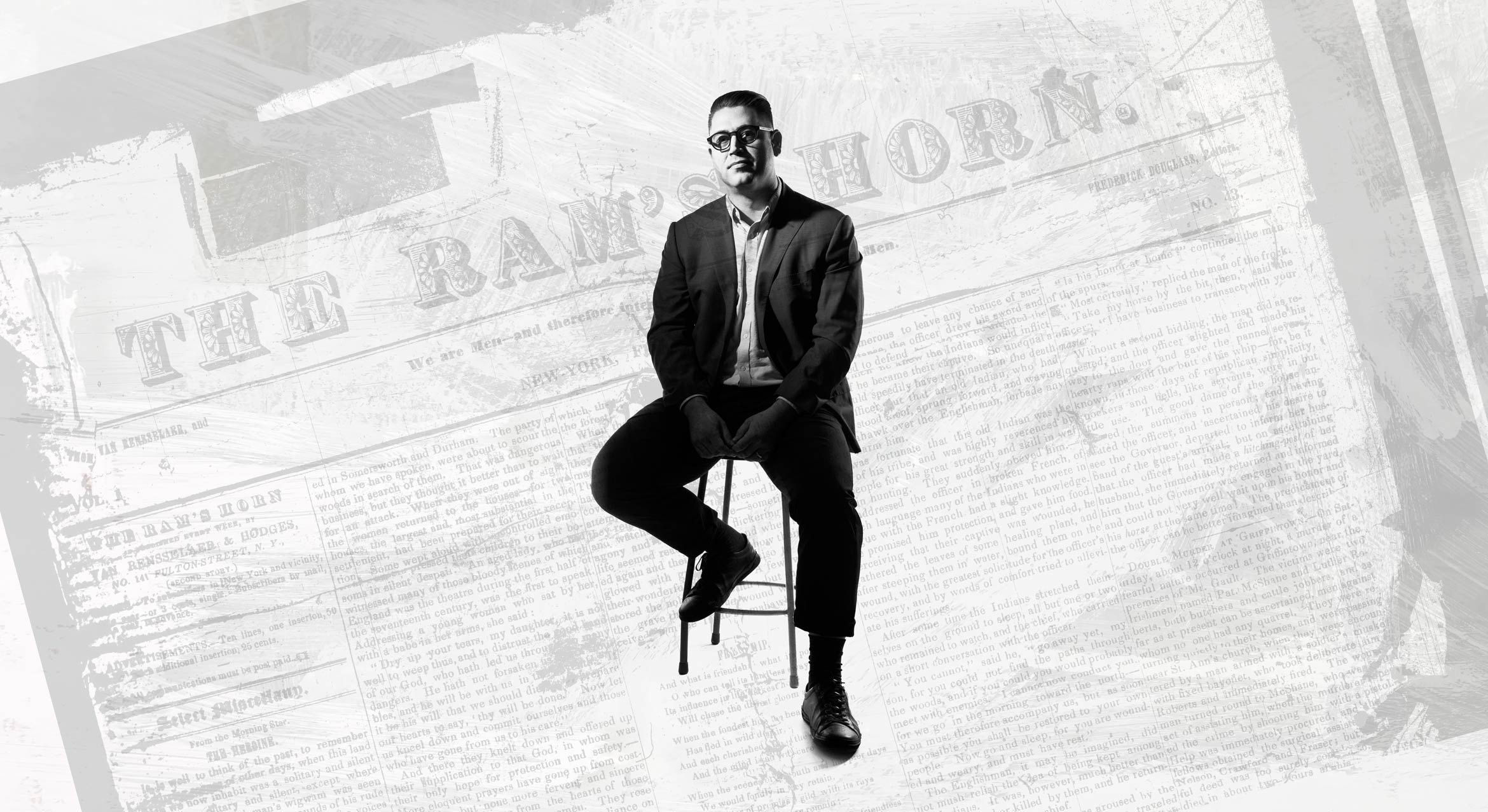

Zachary Liebhaber, an archival processing specialist at the UCSB Library’s Department of Special Research Collections who led the digitizing effort, said Fernald’s copies — which are stored in a climate-controlled vault — were too brittle to be handled. Getting them online, he said, will give everyone the chance to explore them.

“I’m just so pleased because these issues are now in a safe storage environment,” Liebhaber said, “but we’ve made them more accessible at the same time. And for me, that’s what it’s all about. We’re also really grateful to our public library for choosing us to be the custodian and the face of this newspaper.”

The high-resolution (440 dpi) images can be downloaded and viewed at leisure with software like Adobe Reader. That’s valuable, because compared with today’s graphics-heavy newspapers, the Gazette is a giant block of text over five columns.

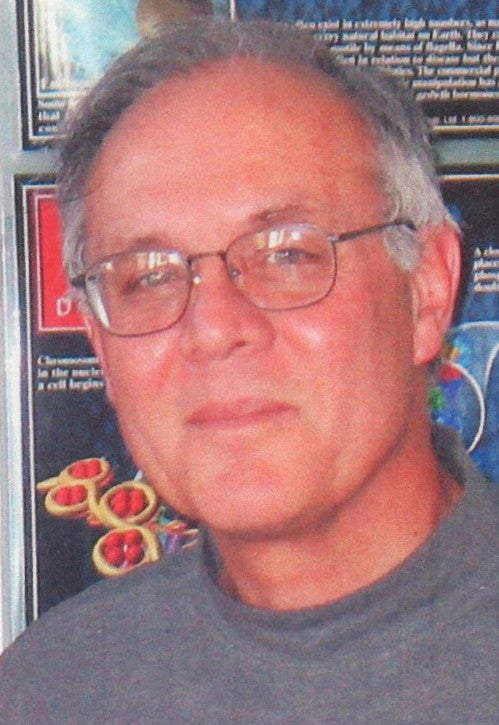

But a dive into those columns reveals a world both familiar and strange, one with a mayor named de la Guerra and an explication of siege warfare. Most importantly, historians say, is that it illuminates a critical transition period from Spanish-speaking Californios to an Anglo majority, Michael Redmon, a historian at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum, told the UCSB Library earlier this year.

“This is the period of some of the first challenges to the traditional power bases in the city’s political and judicial systems,” he said. “A political shift had begun and tensions in town were high.”

Anne Petersen, executive director of the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation, noted that many of the Californios felt they were getting a raw deal from the Anglo-Americans — from having their adobes razed for new streets to feeling as though their rights to their lands were being whittled away.

At the same time, the Californios were still influential. When the Gazette first published, Pablo de la Guerra was mayor. Other Californios, particularly the Carrillo family, were key figures in the development of the state. Jose Carrillo succeeded de la Guerra as mayor in 1855. (The vote count, as reported in the Gazette’s July 26, 1855, edition: Carrillo, 71; Joaquin de la Guerra, 45; and C.R.V. Lee, 30.)

Petersen, who earned a Ph.D. in public history from UCSB, said that while the Gazette is a great asset for historians and others, she cautioned it’s just one voice from the past.

“It’s an incredibly interesting time in the early 1850s,” she said, “but with the caveat that you’re not getting all the perspectives within the newspaper coverage. You’d have to look elsewhere, like personal family collections or other archival materials like letters to find some of those other voices.”

Liebhaber agreed, noting that “the Gazette is a published, public record, with all the omissions that implies, and should be read with that in mind.”

Tantalizingly, it’s possible the Gazette published for as long as five years, said Jim Campos, a local historian who has been researching the lynching of a man and his son in Carpinteria on Aug. 23, 1859. He believes the Gazette’s publishers moved to San Francisco and continued printing it for two more years — although those issues are lost.

“They just didn’t keep it going in Santa Barbara,” he said. “They moved to San Francisco apparently, and they kept it going for at least two years. That’s been kind of the word that comes down, but there wasn’t any proof because we don’t know where Volumes 3 and 4 of the Santa Barbara Gazette are; they’re lost. So all we’ve got is the two years from ’55 to ’57.”

Then came what he calls his “great discovery.” Through a professor at the University of Nevada Las Vegas he obtained a Spanish-language newspaper, El Clamor Público, published in 1859. It included an account of the lynching that it said was translated from the Sept. 1 issue of the Gazette. Because the paper’s publishing year was May to May, he said a September 1859 issue means it was in operation for a fifth year.

In addition, a letter in El Clamor Público claimed that the Gazette’s account of the murders was inaccurate.

“It’s interesting because you can read his letter and then read what’s published in the Gazette,” Campos said. “It’s an amazing kind of a thing.”